Do you have resting-poor-face?

A new study claims we can tell rich from poor in split seconds

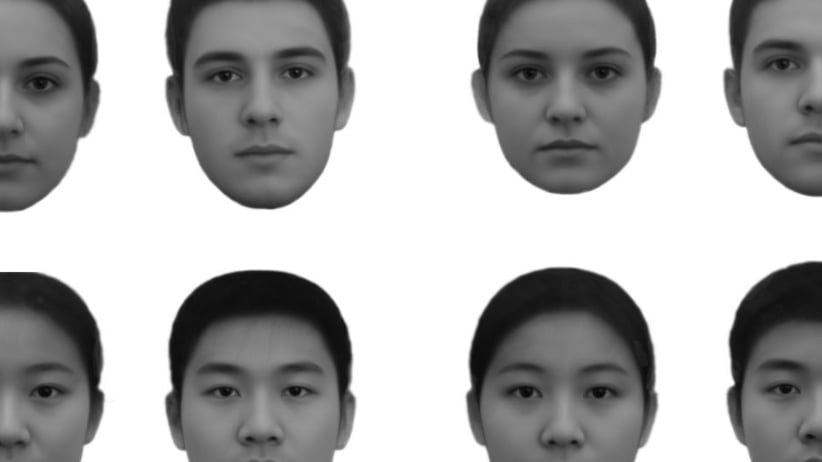

Facial cues to Social Class. Composite images used in Study 5A: (A) rich Full Composites, (B) poor Full Composites, (C) rich Best Composites, (D); poor Best Composites; Caucasian female, Caucasian male, East Asian male, and East Asian female faces presented clockwise from the top-left corner with each array. (Thora Bjornsdottir and Nicholas Rule/University of Toronto)

Share

Rich or poor? The answer may be written on your face.

A recent study by researchers at the University of Toronto has found that we are able to judge a person’s income with surprising accuracy just from a glimpse of the face.

Researchers conducted the study by asking participants to categorize photos of people as rich or poor. In one stage of the study, photos were collected from dating sites and individual income was self-reported as either more than $150,ooo or less than $35,000. A second set of tests used photos captured in a lab, featuring 156 undergraduate students with neutral, expressionless faces whose household incomes were either below $60,000 or above $100,000. Only Caucasian and East Asian students featured in the photos, in an effort to account for racial bias or stereotyping by participants, according to Nicholas Rule, associate professor of psychology at U of T who worked on the study.

Those asked to categorize the photo subjects by income level were accurate 68 per cent of the time in the first study and 52 per cent of the time in the second, more controlled set, even when given only split seconds to make their choice. Statistically, peoples’ guesses in both studies were too high to be pure chance, according to Rule, who says he was astonished by their accuracy, given that subjects of the second study were purposefully devoid of expression. “Those [differences] are just so extremely subtle in someone’s appearance and the fact that people were picking up on this and extracting that information from the face so readily really did surprise me,” said Rule.

The findings of the study, which Rule co-authored with Thora Bjornsdottir, are both fascinating and troubling. They have implications in hiring, law enforcement and our day-to-day interactions with colleagues and peers. If you grow up poor, to some degree, you’ll always look it—and face the subconscious bias of those who can tell. “You look a certain way, people treat you a certain way—people treat you like you’re poor; it’s a cycle you can’t get out of,” says Rule. By the same token, those who are deemed richer—because they seem happier or more attractive—may be given opportunities and treated better as a result of their perceived wealth and the positive traits we seem to associate with it.

It’s not something to take lightly—these are judgements we make on a daily basis, scrolling through newsfeeds and ‘liking’ our friends’ pictures. Gordon Patzer, author of The Physical Attractiveness Phenomena, who studies the power of beauty on perception, says that the prevalence of social media—like Facebook or Tinder—will only continue to make faces a key way we evaluate our peers (and strangers). “We rely so much on photos on social media…I would have to speculate that [we’re putting] more and more importance on a person’s image all the time.”

At the heart of peoples’ correct guesses in the study is the stereotype that the rich are happier due to their less arduous childhoods and lifestyles, and vice versa for the poor. The study found that faces people associated more strongly with positive traits such as attractiveness and empathy were more often labelled wealthy. To be sure, in all the photos taken in the controlled lab setting the subjects appear quite glum—but the wealthy just looked a little less so.

The giveaway, it seems, is the mouth. Part of the study involved asking people to guess incomes while only seeing parts of a subject’s face—the mouths rather than eyes were the strongest, most accurate indicators of wealth. All it took to skew the accuracy of participants in their exercise was to categorize images of smiling people—a grin erased any cues people could use to make their choice.

READ: Canada must get serious about income inequality. But how?

“The face changes over time. Your mom might’ve always said ‘if you make a funny face, it’ll stay that way.’ There’s a kernel of truth in that, it turns out,” says Rule. The face has 43 muscles and they’re no different than the other muscles in your body—the more you work them out, the larger they’ll get. The smiling, happy childhoods of the rich had left imprints on their faces.

It’s an awkward truth that we may shy away from wanting to acknowledge for fear of perpetuating stereotypes. “In my opinion it’s far more dangerous for us to pretend the stereotypes don’t exist,” says Rule.

By burying our heads in the sand we might just never solve the problems our first impressions lead us to. For instance, in the last part of the study, Rule assembled a group of participants and asked them to rate how likely the subjects were to be hired as accountants (a profession that was chosen since it isn’t associated with wealth or poverty). The rich won out here, too.

But where did this specific knack for visually categorizing people by their income status come from? There’s an evolutionary argument to be made, speculates Rule, that as humans we would want to know what resources our peers have access to so we could decide whether we’d want to continue associating with them. Indeed, there are studies that suggest that our ability to convey emotions via facial expression—and to interpret them—evolved throughout time and became important skills in predicting behaviour.

While disconcerting, the results are a step towards progress, says Rule. If perceived wealth and our feelings towards class can affect hiring decisions, then perhaps hiring managers need to be trained accordingly. Being aware of their biases means they can make an effort to change the way they perceive people. Acknowledging you have a problem is the first step towards recovery, after all. On the other hand, if people are aware that they’re being judged subconsciously, as Patzer suggests, they can make changes to how they carry themselves to combat their resting-poor-face.

“If we want equality as a society, we need to face some of the facts about things we don’t like, which is that we do judge people based on their appearance and we do use stereotypes to do that,” says Rule.

So, next time you have a job interview, you might want to practice donning the slightest of smiles—it may level the playing field, if only just a little bit.