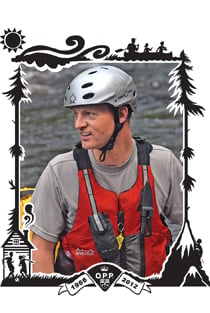

Douglas William James Marshall

He loved the outdoors, and was determined to become a police officer. He understood the trauma crime caused its victims.

Share

Douglas William James Marshall was born at Toronto Western Hospital on July 16, 1966. He was the third of three children born to Sandra, a homemaker, and Don, who ran Marshall’s Refrigeration, an air conditioning business. Doug, his sister, Colleen, and brother, Steve, grew up in Scarborough, Ont., on a tree-lined street where the road hockey game never seemed to end.

Doug was a friendly and inquisitive kid who loved exploring outside. He would tromp through the wildernesss on the family’s frequent camping trips, and wander the woods when visiting his grandparents in Parry Sound. He was known for his thick, velvety blond hair. “Everybody always wanted to touch his head,” says Sandra.

At 11, Doug met Mark Pelzl, and started helping him with his paper route. “We were like brothers,” Mark says. They remained tight through their teens, along with a growing circle of friends brought together by their love of nature. “Any long weekend, we were rock climbing or going up to Algonquin Park,” says Mark.

After high school, Doug moved to Orillia to attend Georgian College. Unable to imagine life behind a desk, he was dead set on becoming a police officer. He was 19 when he met Rachael Wheldon, who was studying to be a dental assistant. Rachael wasn’t allowed in the bar where Doug and his friends were hanging out—at 18, she was too young to get in. But Doug slipped away to find her. “He was shy,” says Rachael. “I guess he wanted me, so he turned on the charm and came out of his shell.”

Four years later, sitting under a tree near Lake Couchiching, the raindrop-shaped body of water north of Orillia, Doug asked Rachael to marry him. “That was sort of him: thoughtful and not dramatic,” she says. They tied the knot in September 1990.

By then, in his mid-20s, Doug was an officer with Orillia’s municipal police force. Rachael had their first child, a boy named David, in May 1994. Their daughter Sarah was born June 4, 1996, the same day Doug joined the Ontario Provincial Police. Both kids inherited Doug’s blond hair.

Doug knew that if he wanted to rise through the ranks of the OPP, he would have to serve in a northern Ontario town; stints in isolated locales are a sort of rite of passage in the force. So in 1999, the family moved to Moosonee, a small, mostly Aboriginal community near the southern tip of James Bay. It’s a town without streetlights, only accessible by train or plane. They loved it. “We enjoyed the quiet solitude, the family time, just being away from the hustle and bustle,” says Rachael. Doug devoted his days off to taking the kids on runs and hikes and week-long canoe trips. “All the things he loved to do, he instilled in them,” says his brother, Steve.

Beyond the potential for backwoods adventure, Moosonee was a rough place to work. “There were a lot of alcohol and social problems,” says Const. Eric Lee, Doug’s partner in the town. Because it’s so small, Rachael and Doug would sometimes run into people at the grocery store who Doug had arrested the night before. But it was never an issue; he was known as a courteous man who cared deeply for the town. Doug created a youth soccer league in 2002, and helped a young Cree man enter the OPP. “He always did the right thing,” says Eric. “He was my super cop.”

Over the years, Doug kept in touch with Mark and his old friends. They went camping every year, just like when they were kids. “He was a collector of people,” says Rachael. “He never dropped anybody.”

In 2005, after six years in Moosonee, Doug transferred to Midland, Ont., a town near Georgian Bay in the heart of cottage country. He became a sergeant, and ardently supported a service to help people deal with the trauma of crime. Last summer, after being called out to a series of horrific incidents—drownings, car wrecks, suicides—Doug was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. He was briefly hospitalized, and sent to a clinic for treatment. By mid-January, he was back on the job.

On April 10, Doug left for work on a morning like any other; the family rushed off with quick goodbyes. Alone in the detachment, Doug, who’d never let a friend lose touch, who spent a life fighting crime and helping its victims through their darkest hours, turned his gun on himself. He died of a gunshot wound to the head. He was 45.