Great quotation! But who really said it?

From ‘Beam me up, Scotty,’ to, ‘Nice guys finish last,’ we love to use quotations. Except we use them all wrong, it turns out.

Photo illustration by Sarah MacKinnon and Richard Redditt

Share

“Canadian girls are so pretty, it’s a relief now and then to see a plain one.” This quotation attributed to Mark Twain is quite popular among Canadians. It has been repeated by businesspeople, newspaper columnists and, yes, even Maclean’s in our own Book of Lists. It’s a fantastic line, except for one problem. Twain never said it—at least, not exactly.

Here are the facts: While dealing with legal matters involving his novel The Prince and the Pauper, the author wrote to his wife, Olivia, in a letter dated Dec. 4, 1881, from Quebec: “Maybe it is the [winter] costume that makes pretty girls seems so monotonously plenty here. It was a kind of relief to strike a homely face occasionally.”

The misquote does make Twain’s words more readable by today’s standards. But, as any Twain historian can attest, the words often attributed to him were never his at all. “It’s extremely common—irritatingly common—for anyone to take a witty remark and attribute it to Mark Twain,” says Harriet Smith, the lead editor for the complete and authoritative Autobiography of Mark Twain.

Great quotations seem to find their way to famous names. Nigel Rees, host of the BBC radio show Quote . . . Unquote, coined the term “Churchillian drift” to explain the phenomenon. (Winston Churchill is a quote magnet in Britain.) Rees offers an example from earlier this year, when the U.S. Postal Service issued a commemorative stamp of Maya Angelou with the quote: “A bird doesn’t sing because it has an answer, it sings because it has a song.” The quotation has long been attributed to Angelou, but the original quote belongs to a relatively unknown writer, Joan Walsh Anglund.

“We want famous quotes to come from famous people,” says Fred Shapiro, a librarian at the Yale Law School. “We don’t want to believe that it came from someone we never heard of.” Shapiro’s fascination with quotes started around the age of 10, when his dad bought him a copy of Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations. His love of quotes grew while he worked at the student newspaper at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and where he edited “The Last Word,” a column featuring only quotations. Back then, he admits, he would only name the quote’s author. “Now I hate it when people do that, because I feel that it’s not a real quotation,” Shapiro says. “Giving a source beyond the name of the author is the earmark of a real quotation,” such as the name of the book or date of the speech in which it was used.

Shapiro edited the first Yale Book of Quotations, published in 2006, now deemed by experts to be the most authoritative quotation dictionary. At more than 1,100 pages long, Shapiro thoroughly researched each one of its 12,000-plus quotations back to its earliest source.

And while the Internet is his best tool in the hunt for authenticity, it’s also his biggest foe. “The Internet has different methods of propagating quotations,” Shapiro says. “Sometimes people put a quote as part of the signature of their emails. There are now Internet memes that spread like wildfire.”

Still, even quotations that can easily be fact-checked by watching a film find their way into pop culture as misquotes. When Rees started writing a book about memorable movie quotes, “I was appalled,” he recalls. “I thought people must have written them down in the dark in the cinema.”

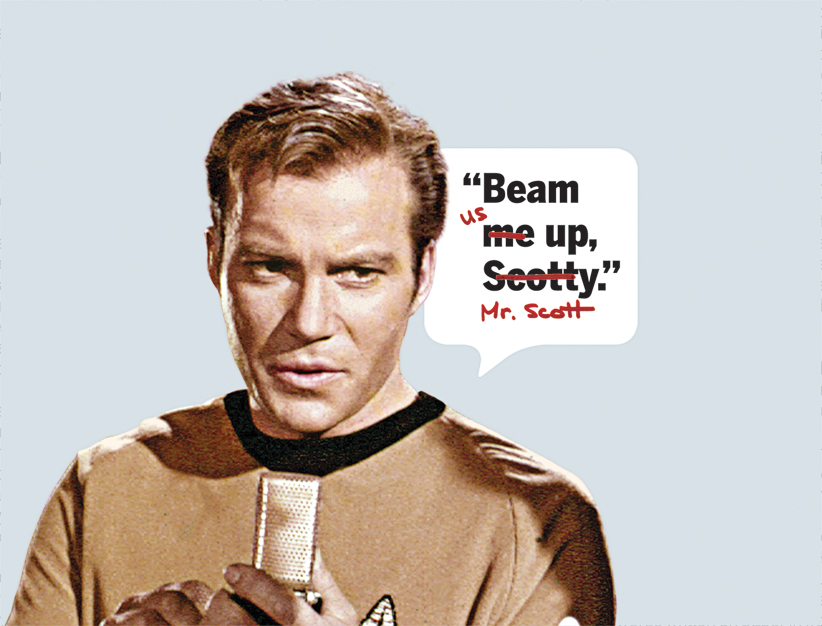

William Shatner’s character in Star Trek never said, “Beam me up, Scotty.” The closest he came was: “Beam us up, Mr. Scott.” Kevin Costner’s character in the baseball classic Field of Dreams doesn’t hear a voice saying: “If you build it, they will come.” The words in the movie, based on the novel Shoeless Joe by Canadian writer W. P. Kinsella, are exactly the same as those in the book: “If you build it, he will come.”

Quotes often get condensed in people’s memories. “Memory may be a terrible librarian, but it’s a great editor,” writes Ralph Keyes in his book The Quote Verifier. Leo Durocher, for example, never said: “Nice guys finish last.” When asked whether he was a nice guy, the 1946 manager of baseball’s Brooklyn Dodgers said he wasn’t. He referred to his opponents that day, saying, “The nice guys are all over there. In seventh place.” The National League at the time had eight teams. “What Leo actually said would not be usable as a quotation that has a lot of resonance for Americans,” says Keyes in an interview. “Misquotes invariably improve on real quotes.”

Trying to quote others accurately can be difficult. Keyes frequently says, “Don’t quote me on this,” over the phone. Without the words written on paper in front of him, he says his memory can easily deceive him. At parties with friends, however, he is not one to make a fuss when others misquote. “I don’t go around correcting people,” Keyes adds. “It’s the parking ticket of intellectual crimes.”

Nonetheless, quotations should rarely be accepted at face value, simply because someone repeats them. As the legendary baseball player Yogi Berra once said: “I never said most of the things I said.” But, then again, did he say that?