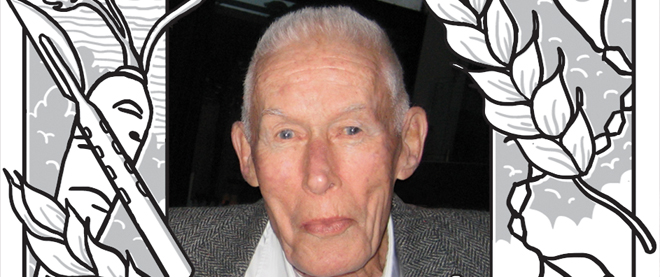

Harold Norman Lynge

A farmboy turned neurosurgeon, he fell in love with a craggy plot of land on the Juan de Fuca strait, and returned every year

Illustration by Julia Minamata

Share

Harold Norman Lynge was born on a wheat farm in the fertile Regina Plains on March 29, 1922, the son of Amelia and Kristian, Lutheran immigrants from Jutland, Denmark. Kristian came to the New World in 1914. He worked in Chicago but returned home twice to woo his bride. Eventually, Amelia agreed to join him. She booked passage to Montreal in 1919. Later that year the two settled on a rented section of land just off the old Soo Highway between Drinkwater and Moose Jaw. Harold arrived three years later. His only sister Marie was born the next year. He had no brothers.

Harold grew up in a farmhouse without running water or electricity. There was never much money, Marie says, but always plenty of food. Amelia canned anything: potatoes, carrots, turnips, even chickens. But at harvest, it was her pies that drew crowds from neighbouring farms. Marie says she had a happy childhood. “But I’m not sure my brother felt the same way. He was a very intense person. He worried about mother and dad and the hardships they were facing.”

During the school year, Harold and Marie travelled by horseback more than six kilometres through the snow to a one-room schoolhouse. Harold rode the faster animal, a great brown beauty named Stuffy. Marie’s mare, Jessie, was older and slower. “When Harold was ill, I was thrilled because I could race his horse,” she says. The early exposure stuck with Harold. He was a dedicated horseman for most of his life. He “could ride anything on four legs,” says his wife, Amy.

The dust-bowl years devastated the Lynge farm, ruining harvests year after year. Doctors survived those years better than most, Harold noticed. So after high school and a failed stint in the navy—he was “whoppingly colour blind,” says his son Dana—he signed up for medical school. He enrolled at the University of Saskatchewan, then transferred to McGill. Eventually, he landed a fellowship at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, where he became a specialist in neurosurgery.

It was at the Mayo Clinic that Harold met a nursing trainee named Patricia Govier. Like Harold, Patricia grew up on a farm in the Canadian Prairies—Manitoba in her case—and the two quickly hit it off. They were married before his training was done. Dana, their first child, was born soon after. Eric, their second son, followed after another five years.

Harold practised in Winnipeg for a number of years, but opportunities beckoned down south. He eventually moved his family to the Bay Area in California, where he worked at a hospital in San Jose and taught at the medical school in Stanford. Life as a neurosurgeon could be hectic. The hours were long and the pressure fierce. But Harold remained even-keeled. “He had a great sense of humour,” Dana says. “I think that helped him survive a lot of stuff.” He also remained a Prairie man, and not just at heart. Even after his children were born, Harold still returned to Saskatchewan every year to help his father with the harvest. “That was dad’s holiday, basically,” Dana says.

In the early 1970s, on a visit to B.C., Harold fell for a plot of land on Vancouver Island overlooking the Juan de Fuca Strait. Harold and Patricia planned to put up a second home on the craggy lot. But in 1976, Patricia was driving north with the blueprints when she suffered an aneurysm and crashed. She didn’t survive the wreck. Building the home became Harold’s passion. “We called it a memorial to Pat,” Marie says. “He finished it the exact way that she had planned.”

In 1985, Harold met Amy Cole on a blind date in San Francisco. The two were married four years later in a ceremony at his Vancouver Island home. Harold instilled his love of the rocky, oceanfront property in his new wife. After he retired in 1992, the two split their time between there and her condo in California.

On April 22, 2011, Harold was driving back to Canada for the summer when he fainted outside his car in Washington State. His health plummeted. He spent weeks in the hospital before returning to San Francisco. Even then, as it became clear he might not recover, Harold never gave up hope of seeing his Canadian home one more time. “It was his driving ambition to get back to that beautiful place,” Amy says. “There was nothing that meant more to him than that.”

On Aug. 26, with his family around him at his San Francisco home, Harold died of pneumonia. He was 89 years old.