Oscar de la Renta: ‘He was in every sense a creature of grace’

Oscar de la Renta dressed first ladies, but his first loyalty was to family and friends

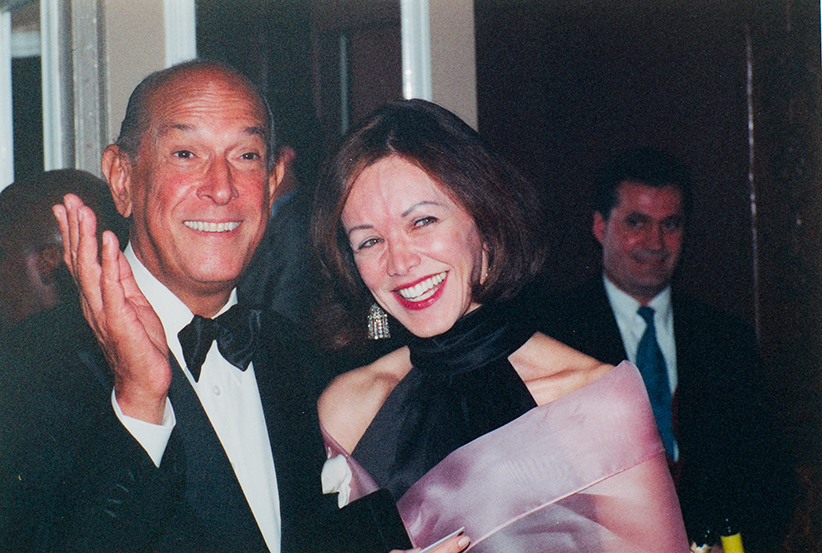

Oscar De La Renta with Henry Kissinger, Annette De La Renta, Patricia Phelps De Cisneros. Photograph by Cole Garside; Courtesy of Barbara Amiel

Share

Oscar de la Renta died last Monday at his home in Connecticut surrounded by family, friends and dogs. By Tuesday, the media was filled with accounts of his life by the many people who had met him. Each has an anecdote or moment. This is mine.

We first met 25 years ago. He and Annette Reed, who was to become his second wife, were the centre of New York society attention. We had all gone to the Metropolitan Opera together, Annette and Oscar followed by flashbulbs. I noticed how protective Oscar was of his fiancée, cradling her from photographers and making sure she was never left alone in milling well-wishers outside our box. That, I thought, is the kind of man I’d like to have at my side.

After I had been lucky enough to marry precisely that sort of man, Conrad and I began to see more of the de la Rentas. Their closest friends were those of Annette’s: Henry and Nancy Kissinger who would re-wear his designs without worrying if they were seasons ago, social doyenne Jayne Wrightsman, Barbara Walters and Annette’s children from her first marriage.

Oscar, I always felt, tried to give me confidence. I was fat by the standards of dress designers and of New York socialites, with all five foot seven of me weighing in at about 129 lb. “Bread is not the staff of life,” the New York ladies would chastise me as I reached for the butter. Oscar saw things differently. “Don’t ever lose your décolletage,” he said when I came out of the swimming pool. I didn’t understand. Sure enough, six years later, I had lost it—the roundness of flesh over bones had been replaced by the semi-emaciated look of bosoms balanced on a pigeon breast structure. I had become fashionably gaunt.

In the early days of building his own label, he was handicapped by competition from the conglomerates. “He has no money to do big advertising campaigns,” Annette would lament. The stylish Park and Fifth Avenue ladies would buy in Paris and then buy Oscar as a backup or loyalty purchase. Oscar just kept working. By the time we went to his house in the Dominican Republic to see in the new millennium together, Oscar was dressing America’s first ladies of politics and screen and no one bought his clothes as a second choice anymore.

From 1992 to 2002, he worked in the haute couture at Balmain in Paris, the first American heading a house in the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture. The strain of travel between New York and Paris was enormous, particularly as the fashion agenda invented new seasons to please wealthy consumers: “pre-fall” and “resort,” each demanding new shows for his own label, as well as Balmain.

He was in every sense a creature of grace. The little baby boy found on top of a garbage can near his home in the Dominican Republic was adopted by him and named Moises, a life turned upside down in the best possible way. His loyalty to family and friends was unflinching and he had no fear of giving newcomers a chance—or old comers a second chance, as he did when he brought the maligned John Galliano to work with him last year. During my travails when I was no longer a good social bet buying lots of ball gowns, Oscar did not waver. A trunk show of his came to Florida and a horrid New York tabloid wrote I had purchased $25,000 of Oscar’s clothes. Oscar himself called to apologize and tell the newspaper it was fiction.

When last summer I was invited to a wonderful ball in the U.K., I chose an Oscar gown from Toronto’s “the Room” at Hudson’s Bay. Unfortunately, it was strapless and my arms and chest were in the decay Oscar had foreseen. I emailed him in despair. “Wrap yourself in clouds of tulle,” he said. A package of tulle, via his close colleague Boaz Mazur, arrived in Toronto. I wrapped myself in it and swanned in. Just as I know Oscar, a practising Roman Catholic, fine and decent, of charity and mercy, will now be wrapped, exalted and luxuriating in heaven’s embroidered cloths of gold.