Knocking people off their feet

The latest in geriatric research looks at slips, trips and tumbles

Sunjoo Advani

Share

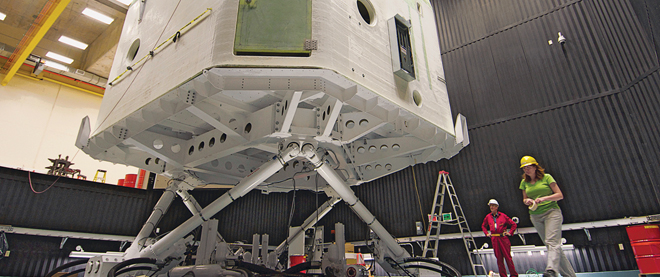

Visitors to the basement of the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute’s new 13-floor building on “Hospital Row” could be forgiven for thinking they had unwittingly stumbled upon a super-villain’s subterranean lair. Several floors below the ground, technicians monitor computer consoles perched above a deep chamber that houses three giant fibreglass pods—each with an interior about the size of a spare bedroom. A claw-like system dangles from the ceiling, waiting to hoist one of the pods off the ground and carry it along a track into a neighbouring chamber, where it is placed atop a set of giant hydraulic legs bolted to the cement floor.

Visitors to the basement of the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute’s new 13-floor building on “Hospital Row” could be forgiven for thinking they had unwittingly stumbled upon a super-villain’s subterranean lair. Several floors below the ground, technicians monitor computer consoles perched above a deep chamber that houses three giant fibreglass pods—each with an interior about the size of a spare bedroom. A claw-like system dangles from the ceiling, waiting to hoist one of the pods off the ground and carry it along a track into a neighbouring chamber, where it is placed atop a set of giant hydraulic legs bolted to the cement floor.

There are, however, no plans to take over the world with this high-tech equipment, part of the institute’s new Challenging Environment Assessment Lab, or CEAL, a computer-controlled motion simulator system similar to those used to train pilots and astronauts. Except these simulators, part of a $36-million initiative to make Toronto Rehab a leader in geriatric and neurological rehabilitation research, will be used to replicate more mundane environments like icy sidewalks and household staircases—both of which are responsible for a staggering number of injuries among elderly and disabled Canadians every year. “We take on the big problems,” says Geoff Fernie, the vice-president of research at Toronto Rehab, as he levels his gaze over the glasses perched on the end of his nose. “Stairs kill and maim three times as many people as car accidents.”

In Canada, one out of three people over the age of 65 has a slip or a fall every year, and they are responsible for nearly 20 per cent of injury-related deaths and two-thirds of all hospitalizations among the same age group, according to the Public Health Agency of Canada. And falls break more than just brittle bones. They also shatter confidence and can often mark the beginning of a rapid decline in health and quality of life among the elderly, a growing national health issue for an aging Canadian population.

But how will flight simulator-like equipment prevent seniors from taking a nasty spill inside their homes, where most falls are likely to occur? One of the three pods, called StairLab, is a good example. Inside, a test subject dons a harness and walks up or down a small staircase while the motion simulation equipment is used to trigger a loss of balance, with a series of cameras capturing every detail so the fall can be studied later. It’s billed as a much more accurate way to determine why falls actually happen in real life, and how relatively small changes can prevent them, ranging from changes to stair dimensions to treads and banister design. (As it turns out, one of the chief culprits for stairway-related accidents in the home is a lack of nosing on the landing, which alters the length of the first step.) “Our view of rehab is to try and prevent people from having accidents so they don’t have to come to the hospital in the first place,” Fernie says.

Similar tests take place in another pod called WinterLab, although the focus here is on slick surfaces like ice-covered sidewalks and roads, which are replicated with the help of refrigerated floors, giant fans and sub-zero temperatures. Sunjoo Advani, CEAL’s simulator consultant and the president of the Netherlands-based International Development of Technology, says WinterLab offers researchers a much more accurate way to test, say, the grip of a pair of winter boots, by using live subjects in real fall situations. “As soon as you change your stance it affects the performance of the boots right away,” says Advani, whose background is in flight simulation technology.

Perhaps the most interesting of the pods is StreetLab. It contains a treadmill and wraparound video screen that allows subjects, including patients recovering from brain injuries, to walk down a familiar street while the motion system provides all of the necessary feedback. Meanwhile, researchers can control the level of vehicle and pedestrian traffic encountered in the make-believe world, allowing them to better understand how sensory signals are processed by injured and uninjured brains. (One hiccup: the software was coded in India, and early versions depicted all white people wearing heavy coats even on balmy-looking days—an oversight since corrected.)

Though rehabilitation has never been viewed as a sexy area of medical research, Fernie believes the new tools will go a long way to establish it as a place where state-of-the-art technology is used to solve long-standing and seemingly intractable health problems. “The perception of graduate students and others is that you’re going to see people walking back and forth between parallel bars and you’re going to be measuring angular knee velocity or something,” he says. “Well, we’ve turned that on its head.”