The Taliban, polio and YOU

A Science-ish Q&A, plus our INFOGRAPHIC showing how the disease could spread again in Canada

Share

With the recent outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases—whopping cough and measles—in Canada and the U.S., public-health commentators are reminding us that the failure to get our shots (and boosters) is not only a threat to our personal health, but also to those around us. This aphorism is repeated all the time when it comes to routine immunization, a warning about how easily nearly eradicated diseases can become endemic again.

With the recent outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases—whopping cough and measles—in Canada and the U.S., public-health commentators are reminding us that the failure to get our shots (and boosters) is not only a threat to our personal health, but also to those around us. This aphorism is repeated all the time when it comes to routine immunization, a warning about how easily nearly eradicated diseases can become endemic again.

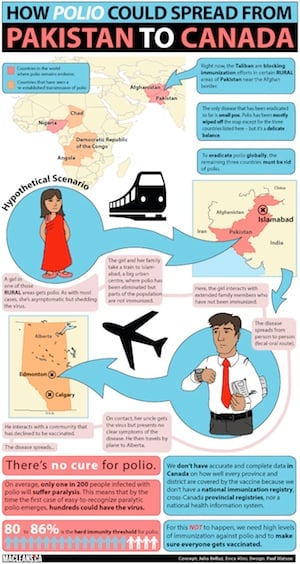

Please click on the infographic to see a full-size version of the image.

To better understand how, exactly, the butterfly effect can play out across borders, Science-ish called Dr. Tariq Bhutta, a Lahore-based pediatrician and chairman of Pakistan’s Polio Eradication Certification Committee, who advises the World Health Organization on polio eradication. The crippling and deadly illness, for which there is no cure, has been wiped off the face of all but three countries—Pakistan, Afghanistan and Nigeria. And in recent years, even places where polio was eliminated, including Canada, have seen resurgences of the virus.

The newest threat to the polio eradication effort is so-called ‘polio warfare,’ waged by militants in the tribal areas of Pakistan who vowed to impede the distribution of the vaccine until the U.S. stops its drone war in the country. This also seems a tit-for-tat for a fake vaccine campaign the CIA staged in an attempt to locate Osama Bin Laden by using DNA from his family. Caught in the middle of the standoff are hundreds of thousands of unvaccinated children, health workers who have been injured or killed, and years of public health progress in the region.

Dr. Bhutta told Science-ish about the surprising challenges of vaccination campaigns in Pakistan, and how a failure to fight polio there could quickly turn into a global threat:

Pakistan is one of the three countries where polio is still endemic. Why? What are the impediments to getting rid of the disease there?

The most important reason is the security situation along the Pakistan-Afghanistan border and the drone attacks by the Americans, which have caused a lot of problems as far as accessibility of the vaccine to children. There’s an active insurgency going on, and a lot of displacement of those children from those areas to other areas where they bring their virus with them and it spreads to other parts of the country. We had two major floods in 2010 and 2011, which displaced millions of people from their homes, as well. Every child could not be reached. So security is the major issue, then accessibility of children in these areas where vaccinators sometimes cannot reach. In very small areas, there might be vaccine resistance due to religious scholars saying that it is not good for our country. And very recently, in the border area, one of the tribal agencies said they will not let the vaccinators come in unless the drone attacks are stopped.

How are the Taliban linking drone attacks to the polio vaccine?

According to them, more children are dying due to drone attacks than from polio. This has effectively caused nearly 300,000 children in that area to be left unimmunized. This may lead to a big hole in the government efforts to stop transmission of polio virus from the country.

What impact might this “polio warfare” have?

The total number of polio cases to date in the whole country is 23—a drop of 67 per cent this year compared to last year. Half of the cases have been reported from the tribal area alone. The chances of stopping the transmission are [still] high but this new development might cause a serious setback to the eradication effort.

You’ve said that if the efforts to eradicate polio in Pakistan are undone, then it becomes a global health threat. How so?

The important thing to remember is that not all persons infected with the polio virus become paralyzed. As a matter of fact, only one out of two hundred infected persons become paralyzed. All the others recover without showing any symptoms except mild fever aches and pain or sometimes loose stool. So if a community has one case of paralysis due to polio, it means nearly two hundred children in the community have been infected and may be passing on the virus to other unimmunized children. That is why the virus can easily move from community to community, town to town and even country to country, as it happened in 2010 when a large outbreak of polio occurred in Tajikistan and hundreds of children suffered from paralytic polio. The virus was found to have travelled from Pakistan. Tajikistan was free of polio for nearly ten years but many children had not been given the polio vaccine during that period. That’s one reason why no country can stop polio immunization unless the whole world is declared polio free.

So all it takes is an infected person reaching a community that hasn’t been vaccinated. Didn’t we see similar cases of spread to Nigeria—a country that had also gotten rid of polio?

Yes, in 2003 Nigerian officials refused to give the polio vaccine to the children under a mistaken belief that the vaccine was a conspiracy against their children. The virus, though, spread again through Nigeria and from there to ten neighbouring countries, which had already been free of polio.

In Nigeria, the fears about the polio vaccine was stoked by religious leaders, who perpetuated myths that the routine inoculations were a plan to either give people HIV or sterilize them. Now, in Pakistan, the Taliban are saying the polio vaccine is a conspiracy by the CIA to similarly harm Muslim children. How do you overcome people’s trust in local leaders for health information?

People do trust religious leaders. In rural areas, it’s primarily a tribal society, and tribal leaders are trusted the most. If doctors have been there for some time, providing health services, they are also trusted. Most of the religious leaders are in favour of giving vaccines and they have been helpful. Even during the Taliban regime in Afghanistan, they were very pro-vaccination, and pro-immunization. When fighting, they would hold ceasefire for a day, and everybody would lay down their arms, and let the vaccinators give vaccine to all the children, and after that was over, they would re-start their fighting. In some cases the mullah of the area or the leader of the clan may not allow the vaccination team to enter the area so children are left unimmunized. It’s important that the tribal leader or the mullah are approached before the vaccination campaign. Right now, the government is employing all measures including political leadership, mullahs and tribal elders to negotiate with the Taliban [who are anti-vaccine]. They have not yet succeeded in overcoming their reluctance in allowing the immunization campaigns. I am afraid it will take a long time to overcome their refusal.

In Canada, we’re grappling with outbreaks of preventable diseases—pertussis and measles—but we don’t have security problems or, really, access problems here…

The story about vaccine problems is common to all countries, both developed as well as developing. The reasons maybe different. In the developed countries, it is usually complacency and when majority of children are immunized, those few who do not get immunized are protected because of herd immunity. So some parents and even some so-called experts may believe that vaccines are not necessary and may be responsible for serious side-effects. In the developing countries, it may be lack of access to these vaccines or the ignorance of the parents which leave many children exposed to these deadly infections. At the same time, in some countries there is strong anti-vaccine lobby—like in India—which prevents the governments from introducing newer vaccines, like the pneumococcal vaccine. It is a constant struggle to keep children safe.

Science-ish is a joint project of Maclean’s, the Medical Post and the McMaster Health Forum. Julia Belluz is the associate editor at the Medical Post. Got a tip? Seen something that’s Science-ish? Message her at [email protected] or on Twitter @juliaoftoronto