Why cancer’s myths can be almost as destructive as the disease

In Malignant Metaphor, journalist and author Alanna Mitchell tries to separate the science of cancer from the psychology

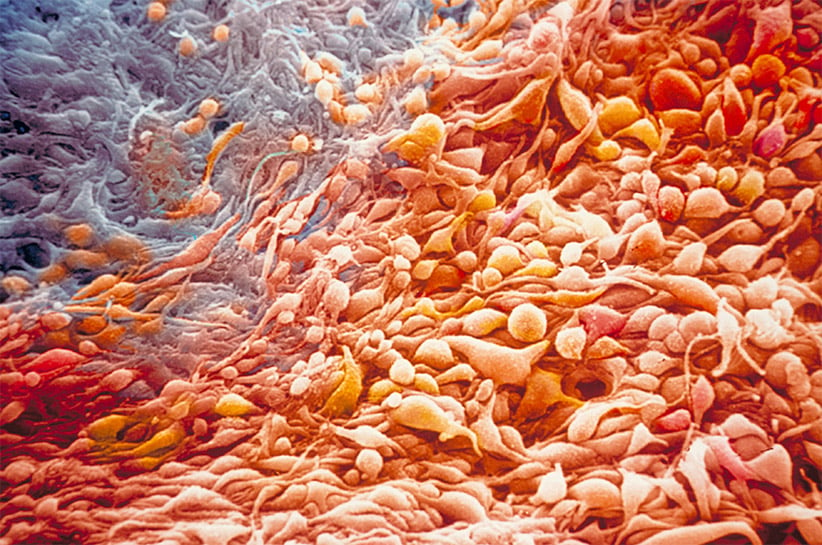

Color enhanced scanning electron micrograph (SEM) of cancer cells. Malignant melanoma of the human iris. (Ralph C. Eagle Jr./Science Source Images)

Share

A few years ago, a professor describing the pervasiveness of cancer asked Alanna Mitchell’s son and his classmates to look at the person to their right and left. “One of the three of you will die of cancer,” he informed them, matter-of-factly. Visions of an imminent and inevitable mass culling ensued. When Mitchell’s son told her about the lesson, she had a startling take of her own: “What the professor ought to have said is that one in three of those brilliant young people will live long enough and healthily enough—dodging infections, accidents and hereditary disease—to die of cancer.”

It is a prudently contrarian view of cancer’s real and perceived threat to humankind that runs throughout Malignant Metaphor: Confronting Cancer Myths by Mitchell, a lauded Toronto journalist and author. The book is a modern incantation of the 1978 classic Illness as Metaphor by American essayist Susan Sontag, which rebuked the guilt complex that patients have about disease.

In Malignant Metaphor, Mitchell tries to separate the science of cancer—how it happens and spreads, who it kills, in which places, and why—from the psychology of cancer, the sense shared by many people that they are doomed to suffer and die of the disease.

At the core of this thinking is a trifecta of irreconcilable beliefs: that cancer is inevitable (we’ll all be diagnosed one day), preventable (as long as we avoid smoking, cellphones, stress, bad food) and deserved (we didn’t exercise/sleep/meditate/forgive enough). “Logically, we know it can’t be all three,” writes Mitchell. “If it’s inevitable, how can it be preventable? If it’s preventable, why does a baby get it or those who lived virtuously their whole lives? If it’s deserved, why do some good people get it and some evil people dodge it?”

Logic, Mitchell concludes, does not prevail when it comes to cancer. Some people might be surprised to learn, for example, that cancer is not, in fact, a global epidemic; in many parts of the world, other diseases kill people in far greater numbers. That North Americans die of cancer so often is actually a testament to how far medicine, science and the administration of health care has come here compared to other places. Eventually, says Mitchell, “something’s got to kill you.”

Even within North America, cancer data presents a different reality than the popular characterizations of cancer as an intractable rogue. “If you look at the numbers in the Western world, huge studies are showing that for the big types of cancer the rates are either steady or declining,” says Mitchell. “It’s not this terrorist that’s going to take our way of life, our civilization. It’s not the punishment that we’ve come to think of it as.”

In her efforts to distill fears from facts, Mitchell is careful not to undermine the devastating impact of this disease. Just about everyone can say they know someone who has died young of cancer, or suddenly, or suffered from it for far too long. “None of this is to try to diminish the horrific nature of getting a cancer diagnosis or what people who have cancer are dealing with,” she says, “because I have seen it. I have lived it.”

Mitchell’s daughter and brother-in-law have both been diagnosed with cancer, and she documents their journeys in Malignant Metaphor. For Calista, a vibrant young woman, it’s thyroid cancer, and she survives it after surgery and two rounds of radioactive iodine. For John, it’s melanoma, and the medical treatment options are limited; he has turned to emerging science and alternative methods such as cancer-cell counting and vitamin C injections. When cancer hit Mitchell’s family, the metaphor was hard to escape even for the objective journalist. In the end, Mitchell realized, “Part of it is just trying to stick your head above the waves for a few minutes to catch your breath,” she says.

Mitchell herself has had a few breast cancer scares since she was in her 20s, which made her “acrid with fear.” After writing Malignant Metaphor, Mitchell faced her next mammogram differently. In dissecting the cancer metaphor, Mitchell had disarmed it. “Right now, in the moment, I am not as afraid as I was,” she thought at the hospital. “And that felt right.”