Zika panic hits the Americas

This side of the Atlantic hadn’t seen Zika virus a year ago—but now it could infect millions

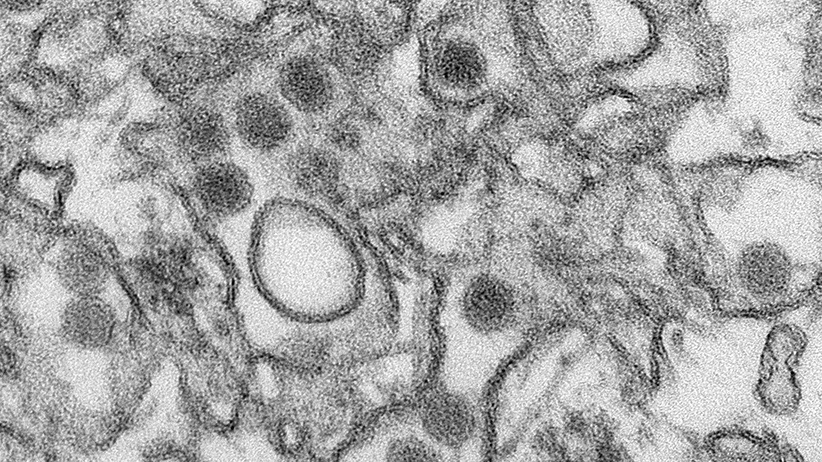

A transmission electron micrograph (TEM) shows the Zika virus, in an undated photo provided by the Centers For Disease Control in Atlanta, Georgia. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) extended its travel warning to another eight countries or territories that pose a risk of infection with Zika, a mosquito-borne virus spreading through the Caribbean and Latin America. (Reuters)

Share

Four Canadians have been diagnosed with the Zika virus, Ottawa officials confirmed today—two from British Columbia, one from Alberta and one in Quebec. All four had recently travelled to Central or South America, where Zika is circulating widely; none acquired the infection at home. “The risk to Canadians remains low,” insisted Chief Public Health Officer Dr. Gregory Taylor, trying to quell mounting fears about the pandemic. Just yesterday, the World Health Organization convened an emergency meeting to discuss the “explosive” spread of Zika across the continent, predicting that up to four million people in the Americas could become infected. As of Jan. 28, Zika was circulating in 23 countries and regions in the Americas—where, a year ago, this virus had never been seen—and WHO officials believe it will reach everywhere in the Americas except for Canada and continental Chile, where the type of mosquito that spreads it can’t survive. There is no vaccine available, no treatment, no cure.

Spread by the Aedes aegypti mosquito, which also transmits dengue and yellow fever, the Zika virus was long thought to be harmless. Its symptoms are generally mild: a fever, rash, joint pain, red eyes. Four in five people have no symptoms at all. The virus has circulated in parts of Africa and Asia for decades at least, but less than a year ago it landed in Brazil. From there, it rapidly began to spread. That country has a huge population of 200 million, the vast majority with no immunity to a brand-new virus. As more and more were infected, startling side effects began to appear. Brazil has seen a twenty-fold increase in babies born with microcephaly, a birth defect causing abnormally small heads and brains. A surge in cases of Guillain-Barré syndrome, which can cause temporary paralysis and, in rare instances, death, has also been seen. Scientists are working to confirm whether or not there’s a link between these and Zika infection, although mounting evidence suggests it is so. (None of the Canadians with Zika are believed to be pregnant.)

In the public health briefing, Ottawa health officials noted that there is a small possibility Zika could be transmitted sexually, or via blood transfusion, which is now being investigated. “The risk [of sexual transmission] is considered to be very low,” said Dr. Theresa Tam, deputy chief public health officer, adding that there has been limited detection of the virus in semen for up to two weeks. She mentioned studies from an earlier Zika outbreak, in French Polynesia, in which three per cent of asymptomatic blood donors had detectable virus in their blood. While there’s not yet international consensus on Zika and blood donation, as a “precautionary measure,” she said, Canadians returning from affected countries are being asked to wait one month before donating any blood.

On Monday, the WHO will convene yet another emergency meeting on Zika, where it will consider labelling the outbreak a public health emergency of international concern, as was done with the Ebola outbreak that spread through West Africa in 2014. “We’ll be watching that [WHO meeting] very closely,” Taylor said. In the meantime, Canadian officials suggest that any woman who is pregnant, or who plans on becoming pregnant soon, consider postponing travel to a Zika-affected area. Some Canadians have heard that message loud and clear: Air Canada and other carriers have announced that passengers can change or cancel flights to any of these regions, free of charge. Of course, not everyone will want to cancel their travel plans. In February, Brazil hosts its famous Carnival, a huge tourist draw; and in August, it’s the Summer Olympics. Australia, for one, has asked its female athletes to carefully consider whether they want to compete in these games, or sit them out.

Around the world, through the Americas and beyond, governments are urging citizens to take various precautions against Zika. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control says that pregnant women should avoid travel to any Zika-stricken region. England’s public health agency has taken the extraordinary step of telling couples who return from any of these places to delay their plans to conceive a baby for at least a month, as a precautionary measure. But the hardest-hit are those who live where the Zika virus circulates. Until a vaccine or treatment is available, they can only protect themselves with bug spray and window screens. El Salvador is among a handful of countries that has reportedly told its female citizens to avoid having children for at least two years, at which point they hope the virus will be contained.