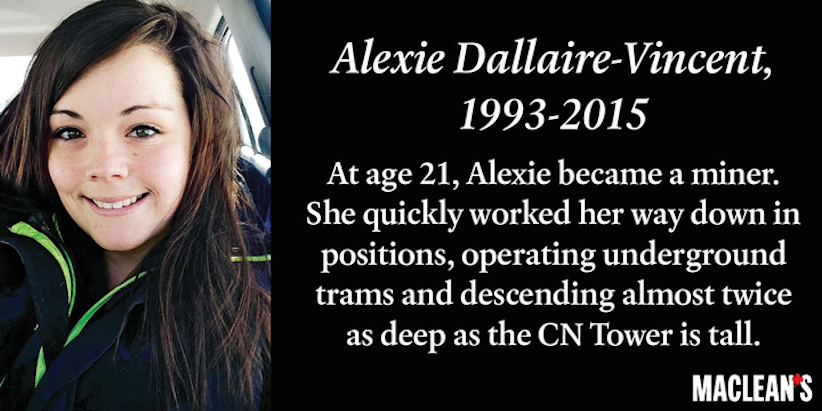

Alexie Dallaire-Vincent, 1993-2015

She stood just four foot ten, but, ever persistent, could lure a yes out of anybody. At 21 she became a gold miner, just like her father.

Alexie Dallaire-Vincent. No credit

Share

Alexie Dallaire-Vincent was born on April 15, 1993, in Virginiatown, Ont., to Mario, a gold miner, and Marcelle, a stay-at-home mom. Her earliest words were French, like her parents, although she soon picked up English to make more friends.

While Mario headed to the mine each day, Marcelle taught Alexie and her older sister, Emmanuelle, to snowshoe and sled. Mario built them the biggest playroom on the block, with Lego, a teddy bear big enough to hide in, and low-set light switches so the kids could flick them off, slip in a video recording, and dance around with Barney.

After Alexie started Grade 1, she accepted little help with homework, often wanting her father to talk less so she could work more. To not be mistaken as younger than she was, she would sometimes cite her exact age to the month and day when asked. Alexie grew up and found jobs in Virginiatown and, later, Matheson, Ont. She refilled the ketchup dispensers at a chip stand, waitressed for restaurants, and, in the gig that sparked her most, ordered parts for a car garage. “If she had kept working there, she would’ve become a mechanic,” says Mario.

On her adult tip toes, Alexie stood just four foot ten. But based on her energy, she seemed to have been at least five feet. Hockey, hiking, renovations—she buzzed. Upon adopting a puppy, she said she couldn’t wait for it to grow up—a rare impatience for the owner of a German shepherd-mastiff mix. Alexie dressed in the flashiest jackets she could find, and for shoe colour, only neon pink would do. The sole time she seemed tired was in the mornings, tasking her mother to repeatedly shout, “reveille!”

Alexie could lure a yes out of anyone. Although incomes restricted Christmas presents to boots and new razors, she knew how to get the things she prioritized—like her mother’s rice pilaf. “You could not say no to her, not with that smile,” Mario remembers. “She would ask and ask, and then her mother would say, fine.” Rice pilaf it was. When her local hockey arena closed down in Grade 7, she spearheaded a rally. “She convinced me it was time to reopen the rink,” says Merdy Armstrong, the town councillor at the time. “As soon as you saw her smile, your day got a hell of a lot better.” At 18, Alexie moved in with her boyfriend, Travis Pepper, a mechanic’s assistant she met at one of her hockey games in high school. Travis became her common-law spouse.

While Alexie never wanted much for herself, she was saintly to others. Her dad once lent her grocery money, only to later discover she gave a quarter of it to a friend for the same purpose. Animals, too, enjoyed her care. As a kid, Alexie slept outside with the pet Labrador, Lucky, during storms, in a doghouse half the size of the kitchen fridge. “Lightning wasn’t allowed to hurt Lucky,” says her father. As an adult, she would lie in bed with her mastiff, both on their backs, sharing the mattress in a 20 to 80 ratio for the dog.

At age 21, Alexie became a miner. Mario suggested she get a job at the St. Andrew Goldfields Holt Mine, where he worked, near Timmins, Ont. She quickly worked her way down in positions, operating underground trams and descending almost twice as deep as the CN Tower is tall. She was the only full-time female employee at the mine, and the managers initially worried about her petite frame. “Mining is a man’s world,” says Mario. “They were afraid she might not have the physical strength.” But with the same smile and “please please please” that got her mother’s rice pilaf, she convinced the managers otherwise. Mario once asked her about getting an easier job on the surface. “She basically told me to take a walk.”

When the guys at the mine complained about their lives, Alexie would perk them up. “Let’s be happy,” her dad remembers overhearing. “We have jobs for the next 10 years.” Her smile couldn’t be tamed, not during her years of braces, and not in the depths of that gold mine.

Last month, Alexie got certified as a search and rescuer at the mine. “It was amazing that they trained her like that so early on,” says Mario. On May 23, 2015, Alexie was working her regular shift, 925 m underground, when she was killed in what the company calls a “rail haulage accident.” The mine paused operations for the day of her funeral so her co-workers could attend. She was 22 years, one month and eight days old.

![THE END [Brown] ROUGHS](https://cms.macleans.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/MAC24_THE_ENDMERGE_POST.jpg)