How to move on from unrequited love

An academic plumbs the roots of obsession to understand her own

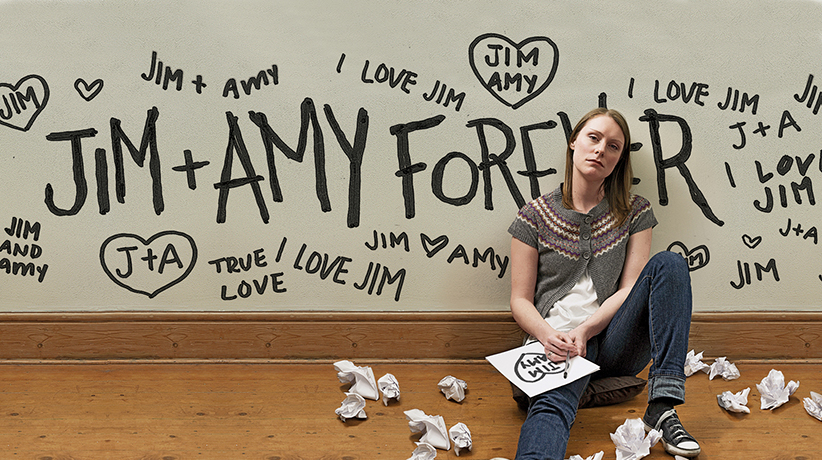

‘Narcissistic linking fantasy’: It is theorized that romantic obsessives idealize love and believe the perfect relationship will complete them. Photo illustration by Sarah Mackinnon and Richard Redditt

Share

Updated Jan. 28, 2018

Early one morning, nearly 20 years ago, journalism professor Lisa Phillips crossed a line. She had fallen madly in love with a playwright who was in a long-distance relationship. He planned to leave the other woman, he said, but then changed his mind. The situation ate at Phillips. She and the man had spent time together, on occasion kissing and cuddling. All she could think about was being with him. In her fascinating book, Unrequited: Women and Romantic Obsession, Phillips confesses she snuck into his apartment building, rode the elevator to the ninth floor and began knocking repeatedly on his door. “Who could reject this kind of desire, desire that walks through security doors and knocks and knocks and knocks?” she recalls thinking. When the man finally came to the door, it was with a baseball bat in one hand and a phone in the other. “Phillips,” he told her, “Get out of here. I’m going to call the cops.”

“My unrequited love became obsessive,” she explains. “It changed me from a sane, conscientious college teacher and radio reporter into someone I barely knew.” It got so bad that at one point, she checked into a psychiatric hospital, where a doctor prescribed a tranquilizer. Years later, she pledged to try to understand the transformation that overtook her when she was 30. She found self-help books aimed at women supplied simplistic advice, such as, “Move on,” or He’s Just Not That Into You, or “play hard to get.” Phillips found none of this helpful. It didn’t take into account the nature of obsession. Because she couldn’t find a good advice book, she wrote one.

Phillips surveyed 260 women about their experience of loving someone who didn’t love them back. She has delved into history and literature, examining famous cases such as the poet Dante Alighieri’s unrequited love for Beatrice Portinari. Dante’s love for Beatrice shaped his life’s work, but the torment was such that he decided not to see her—he would fall apart in her presence. He preferred, instead, to write “words of praise” about her. Phillips also studied the latest neuroscience to understand why romantic obsession happens, to whom it happens, what to take from it, and how to move on.

Narcissism plays a big role, according to psychologist Reid Meloy, who studies stalkers. Meloy’s theory of “narcissistic linking fantasy” explains how romantic obsessives idealize love, believing the perfect relationship will complete them. “I honestly believed this guy was the last man on Earth I could be with,” Phillips says. Facing down her own narcissism “turned the tables for me in a really crucial way,” she said. “Seeing it as very self-centred overturns it as a very cherished paradigm of people who have been rejected. They prefer to think that the other person is narcissistic: ‘You’re so selfish, you don’t want to love me,’ but that’s actually really mixed up,” she says.

If you can recognize that, and see the other person for what he represents, the state of unrequited love can be instructive. Phillips urges readers to consider: “What is our romantic obsession really about? In other words, what are we really yearning for?” One woman she interviewed concluded that her unrequited love represented the career she should have gone after. “There’s a phenomenon of wanting him because ‘I want to be like him,’ which, in adolescence, is called an identity crush but I think it exists for adults, as well,” said Phillips. “If you can recognize what’s happening to you, you can unhook from it and say, ‘Okay, this makes no sense to be in this completely ambivalent relationship with a distant person.’ ”

On the positive side, unrequited love can goad us to creativity. “It’s the phoenix rising from the ashes of disappointment,” she said. It happened to her with this book. “At a time when things were very dark for me, I had a very strong drive to make meaning out of it.” She thought, “I can use who I am as a writer and journalist to investigate this and hopefully offer something important to people who are stuck in unrequited love.”

The best way to move on is to either hear him say he doesn’t love you or be like Dante and cut yourself off. “For me, the magic words were [when he said], ‘We can never speak again.’ ”