Stick family feud

Trivial but powerful, those cartoon family decals—and the backlash against them—say a lot about our times

Share

Dean Pavlovic says he didn’t intend to make a social statement two years ago when he bought two white cartoon stick-figure decals—one to represent him as a dad and one to represent his two-year-old son—for the back window of his yellow Fiat 500. “I didn’t think too much about it,” the 42-year-old Toronto waiter says. “I saw them at Canadian Tire and thought they’d be cute to put in the back of my new car.”

Now, however, he sees that the purchase reflected a defiance he wasn’t aware of at the time. It was just three months after a difficult marital breakup, and he was figuring out his recalibrated life as a parent. He wasn’t trying to signal his newly single status, as a co-worker jokingly suggested. “That was so far off the mark,” Pavlovic says. “I was just proud of my little guy.” But he took definite pleasure in displaying his tiny family unit on the back of a new family car only slightly bigger than a toaster, he says, far removed from stick-figure families’ usual habitat: the rear windows of SUVs and minivans.

There, a conga line of figures, from tallest to smallest, provides smug proof of affluence, busyness and procreative prowess: You’ll see a barbecue dad and a shopping mom, followed by an older girl hockey player, a hip-hop teen boy, a girl ballerina and a baby boy, followed by dogs, cats, goldfish—all duly named underneath. Pavlovic admits that image was in his mind. “OK, maybe in the back of my head, I was thinking, ‘Oh, go screw yourself, SUV riders,’ ” he says. “You take up so much room, you have so much—don’t put it in my face that you also have seven kids.”

Whether you love them or hate them— and many do despise them—few trends reveal shifting family values in a mobile, personal-branding-obsessed society as do family stick figures. Equally telling is the blowback they’ve engendered, a quiet but visual culture war that has given rise to a “My family stickers suck” Facebook page, a stick-family-parody business, even academic attention.

Domestic-status stickers caught on in the U.S. in the early-aughts, the next iteration of yellow hazmat “Baby on board!” signs and “Proud parent of X hockey team player” bumper stickers that offered a way to brand the whole family unit. Neil Carter, a painter-contractor in Hamilton, obtained the Canadian rights to the Australian-based Sticker Family in 2011 after he saw them everywhere while holidaying down under in 2010. He immediately saw potential, he says: “Everybody loves their family and is proud of their kids and likes to show them off. And pets are as much a part of the family as the kids are.”

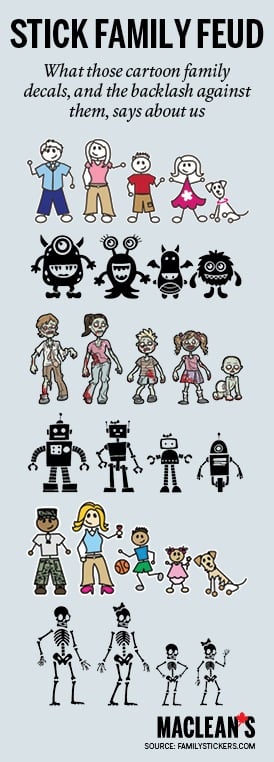

Mass-market stick figures have become increasingly individualized, or as individualized as stick figures can be: “Proud army” families, Star Wars families, cowboy families and robot families. You can buy pregnant-woman figures, figures in wheelchairs—even figures with halos denoting death—on decals, coffee mugs and iPhone skins.

One of the first in the market was San Diego graphic artist Janel Eaton, who runs Decalifornia. In 2006, she told the Los Angeles Times she got her first order from someone who saw them in the Midwest. Her custom orders, which include a four-foot decal of a cowboy surrounded by 23 animals and three mothers with six kids, reflect the expanding—and elastic—definition of family.

Sticker Family, one of many distributors in the field, sells more than 200 figures that can be combined into a family, for $4 each. Carter offers 89 in Canada; his bestseller is “D-4,” a dog they can’t keep in stock. A girl playing an Xbox, on the other hand, was a flop and discontinued. Carter’s own truck boasts a “golfing dad,” “chardonnay mom” and “angel baby girl.”

Carter is part of the stick-family mainstream. But there’s also a Charles Bukowski-esque stick-figure counterculture, a joke-filled, profane, occasionally violent place populated with “We ate your stick family” zombies, “the ass family,” a family hanged with nooses, and former partners with giant “Xs” through them. There’s even quasi-stick-figure porn in the form of “Making my family” decals.

Between those extremes, a create-your-own-stick-family narrative has emerged. Sociologist Lisa Wade, an associate professor at Occidental College in Los Angeles, sees stick-figure families and their evolution as a profound cultural marker: “They’re so trivial, yet so powerful,” she says. “Their story suggests we do still have a family ideal, a norm.” At the outset, stick-figure families seemed to “represent what we’re allowed to be proud of,” Wade says. “They were strongly hetero-normative and supported the idea of having children.” That they showed up on SUVs first is predictable, she says. “When people have four kids, their entire life tends to revolve around their family; that’s their identity—so an opportunity to advertise family-orientedness is appealing.”

What interests Wade most is the blowback to “traditional” stick-family families, from people like Pavlovic. “This is activism happening, when you see couples with no children put decals of two people and piles of money on their cars, or women choosing to put a figure of a woman with a cat, or six.” Identifying yourself as a same-sex couple is another form of resistance, Wade says: “It’s very visible. They’re not coming out to somebody; they’re coming out to everybody.”

Taking those risks is a positive development, Wade believes, one that reflects increasing social tolerances: “Studies are showing that Americans have a pretty broad definition of what counts as a family these days,” she says, pointing to the American historian Stephanie Coontz’s observation that never before in history have so many variations of the family form lived together in the same time and place.

Though the trend of stick-figure families took off just as the “traditional” triangulation of male husband and female wife with kids was on the decline, it still reflects ingrained thinking about proper family hierarchy, affirming the old “man as the household head” model, Wade says: “They’re always ordered in ways that are about men being dominant; the man is usually the first figure. They also affirm the idea that all men are bigger than all women.” (The popularity of stick figures at a time when obesity is on the rise might be sheer coincidence, or not.) Their presence also reveals how stick figures in the public realm are, by default, seen as male, says Wade, who has written about gender roles and stick figures. Decal-makers may try to be gender-neutral, but they’re going to fail, because the stick figure is never gender-neutral, Wade says. “If it’s a stick figure with a soccer ball, it looks like a boy, and if it’s a stick figure without a soccer ball, it looks like a boy. And if you look at two figures and one is taller than the other, everyone reads the tall one as male. To make it a woman or girl, you have to use gender signals—a skirt or a ponytail.” It’s impossible to avoid reinforcing gender stereotypes, Wade says. “That’s how power works.”

Related:

Maclean’s long reads: Our collection of thought-provoking longform journalism

Stick-figure families may express family pride, but their popularity has also given rise to the fear-mongering, paranoia and sense of precariousness that can accompany modern parenting. “How car stickers are putting your family at risk” is a familiar headline, with both police and media issuing the self-evident warning that too much information about your life and children—their names, their hobbies—enables pedophiles. Although there has yet to be a case linking criminal behaviour to stick-figure profiling, worries are being aired that enterprising thieves will know which cars to target for sports equipment, or whether a dog is of “guard-dog” quality. Earlier this month, widespread media coverage was given to an Ohio search-and-rescue team’s warnings on Facebook that used the example of stickers depicting an “army dad” and “football son”: “The father is never home; he’s overseas . . . It’s likely his mother takes [the son] to practice after school, giving criminals ample time to raid their home.”

Despite such dire warnings, stick families, in all their permutations, show no sign of disappearing, something that surprises even people selling them. “I thought the business would have a two- to five-year lifespan,” says Carter, “and the first year was explosive.” Now in year three, sales remain steady, though he wonders if market saturation has been reached. Pavlovic says his own personal tolerance has hit the wall. He’d like to remove his stick-figure decals from his car, now that they’re so common. There’s only one obstacle: his four-year-old son. “He won’t let me,” he says. “He’s proud of them.”