Coffee pods: The new eco-villain

The K-Cup backlash has prompted the disposable coffee system’s inventor to change his tune

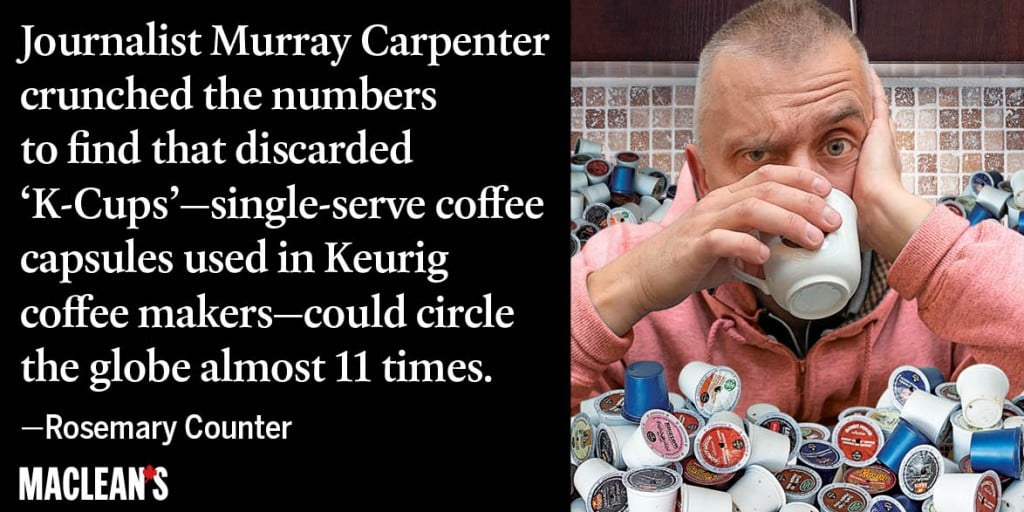

Man drinking a cup of coffee and drowning in coffee pods. Photo Illustration by Sarah MacKinnon and Richard Redditt

Share

Update, March 6, 2015: K-cup creator John Sylvan has said that he regrets creating the disposable coffee pod system because of the negative environmental effects. “I don’t know why people have them in their house,” he told the CBC.

In his 2014 book on coffee, Caffeinated, journalist Murray Carpenter crunched the numbers to find that discarded “K-Cups”—single-serve coffee capsules, or “pods,” used in Keurig coffee makers—could circle the globe almost 11 times. That meant 8.3 billion in 2013, and that’s not counting Tassimo or Nespresso or other big-name makers of coffee pods. Canadians are big fans of single-serve brewers; 20 per cent of households own one, compared to 12 per cent of Americans. But with massive growth comes massive garbage: Since they’re largely unrecyclable, almost all coffee pods end up in a landfill. They have not yet taken on the bad rap of the plastic water bottle, the eco-villain of our times, but mounting garbage piles of pods are becoming increasingly hard to ignore. A new video called “Kill the K-Cup,” featuring discarded pods in Godzilla form, is making the rounds on YouTube this week.

It dovetails with a broader K-Cup backlash, a response to the revamped Keurig . The “new generation” Keurig 2.0 won’t work with off-brand or even old K-Cups, and can no longer be refilled with your own grounds. Consumers have retaliated with a plethora of “hacks” to sneak off-brand pods into Keurig machines: KeurigHack.com suggests removing a K-Cup lid, with its proprietary logo, and taping it to the top of the machine’s infrared reader; meanwhile, a California coffee company is offering the “Freedom Clip,” a plastic clip that overrides Keurig’s lockout technology.

But right now, the EcoCup coffee pod, also made in Canada (and not without its isssues—critics say it cannot be recycled in many markets) can’t be used with the new Keurig. Nor could Club Coffee’s new compostable pod, whose ring, filter and lid are all made with different, compostable, components. The product launches later this year. Already there are bumps in the road. Toronto-based Club Coffee has filed a $600-million lawsuit in Ontario against Keurig, alleging the firm has misled retailers by claiming that off-brand pods are incompatible with their machines.

In Canada, at least, there is growing demand for greener options. As the company TerraCycle has discovered, we’re willing to pay to ease our eco-guilt. Specifically, we’ll pay $137 a pop for TerraCycle’s large Zero Waste Box, which launched last August. “There’s no question it’s expensive,” says Toronto founder and CEO Tom Szaky. But as more people sign up for the premium service, the price has fallen from its original $180. Szaky says it will drop further. Here’s how Zero Waste Box works: Customers choose from 69 different boxes at their local office-supply store, each with a different category of waste (from generics like “bathroom” to specifics like “makeup” and, of course, coffee pods). Fill up the box, UPS picks it up (postage is included), and TerraCycle recycles it. A large box fits 2,000 pods. These go to a processor in Fergus, Ont.; plastic components are made into park benches and the coffee residue is used by local farmers.

Coffee pods—maybe because you see them five times a day—are on the top end of the guilt hierarchy, Szaky says. TerraCycle’s pilot program in Ontario has proved so successful they’re now rolling out the coffee-pod box across Canada. “Recycling your coffee capsule is not the answer to waste,” he admits, “but for whoever chooses these capsules, here’s at least something you can do.”

Of course there’s another option. “I would never allow myself to purchase a single-use product like this,” says Stefenelli. “I modify my habits as to not fall into the trap at all.”