After every trip to the bathroom when he’s at home or in a hotel room, BJ Fogg will get down on the ground and do two push-ups. Then he’ll wash his hands. It sounds kind of weird, if you stop to think about it, but Fogg doesn’t think about it anymore. It’s a habit he has worked to develop over the past two years to help get in shape. Now, the push-ups come automatically and he gets a surge of energy each time. Often he doesn’t stop at two. On some trips, he might do 10 or 25. “I probably did 50 or 60 push-ups yesterday,” he says.

Fogg is perfectly placed to train himself into a healthy habit. He is an expert on the subject, having studied human behaviour for 20 years, mostly at Stanford University, where he’s the director of the Persuasive Technology Lab. From his research, he’s learned that the best way to automate a new habit is to set the bar incredibly low. Ergo, just two pushups. “You pick something so small, it’s easy to do. Motivation isn’t required to do it,” he says. Even though he’s become much stronger, he says, he’ll never raise the minimum. The goal remains two push-ups, and anything more is a bonus. “If you want to maintain the habit, you will always be okay with just doing the tiny version of it,” he says.

Habits are important because, as Gretchen Rubin puts it, “what we do every day matters more than what we do once in a while.” When Rubin published the massively bestselling The Happiness Project, she laid out personal commandments and explored the overarching principles in her year-long journey to enjoy life to the fullest. In her new book, Better Than Before: Mastering the Habits of Our Everyday Lives, Rubin narrows her view dramatically, turning to the daily routine actions that make up our days. “Habits are the invisible architecture of our lives,” Rubin says in an interview. In fact, studies have shown that approximately 40 to 45 per cent of what we do every day is a habit—something we do by default. When we wake up, we brush our teeth. We get in the car to go to work and, without thinking, we put on our seatbelt. There’s no decision-making at work. It’s automatic. “If you have habits that work for you, you’re much more likely to be happier, healthier and more productive.”

Habits are important because, as Gretchen Rubin puts it, “what we do every day matters more than what we do once in a while.” When Rubin published the massively bestselling The Happiness Project, she laid out personal commandments and explored the overarching principles in her year-long journey to enjoy life to the fullest. In her new book, Better Than Before: Mastering the Habits of Our Everyday Lives, Rubin narrows her view dramatically, turning to the daily routine actions that make up our days. “Habits are the invisible architecture of our lives,” Rubin says in an interview. In fact, studies have shown that approximately 40 to 45 per cent of what we do every day is a habit—something we do by default. When we wake up, we brush our teeth. We get in the car to go to work and, without thinking, we put on our seatbelt. There’s no decision-making at work. It’s automatic. “If you have habits that work for you, you’re much more likely to be happier, healthier and more productive.”

“We are what we repeatedly do,” wrote historian and philosopher Will Durant, paraphrasing Aristotle, in The Story of Philosophy. “Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.” And in his defining treatise on the subject, the 19th-century philosopher William James referred to humans as “mere walking bundles of habits.” But which ones? If almost half the things we do are out of habit, it’s a smart plan to make those habits the right ones. Good habits, in effect, can be the prelude to happiness.

But developing a good habit, or breaking a bad one, isn’t easy, as anyone who has made a New Year’s resolution can attest. The reason: There is no one-size-fits-all solution for habit change, and surprisingly little consensus on how we make habits or break them. Fitness magazines promise great abs in 30 days. Self-help books often deploy the magic 21-day number, suggesting that if you repeat an action for three weeks, it becomes a habit—even though the theory of 21 days may be a gross misinterpretation. In the 1950s, a plastic surgeon named Maxwell Maltz noticed that whenever he performed an operation, such as a nose job, it took the patient about three weeks to get used to the new face. Similarly, if someone needed to have a leg or arm amputated, the feeling of the phantom limb persisted for about 21 days. In 1960, Maltz published the bestselling book Psycho-Cybernetics, which contained his thoughts on taking at least 21 days to jell with one’s new image. From that, a plethora of “Learn to (fill in the blank) in 21 days” programs have taken flight.

There’s no magic time interval to make a habit, however. “The speed of the habit formation is directly connected to the strength of the emotions you feel,” says Fogg. “It has nothing to do with 21 days.”

Rubin’s own quest to discover how habits work was sparked by a conversation with a friend who was on the track team back in high school, and therefore very fit. But now that her regular workout habit was long gone, she couldn’t get it back. Rubin wanted to figure out why.

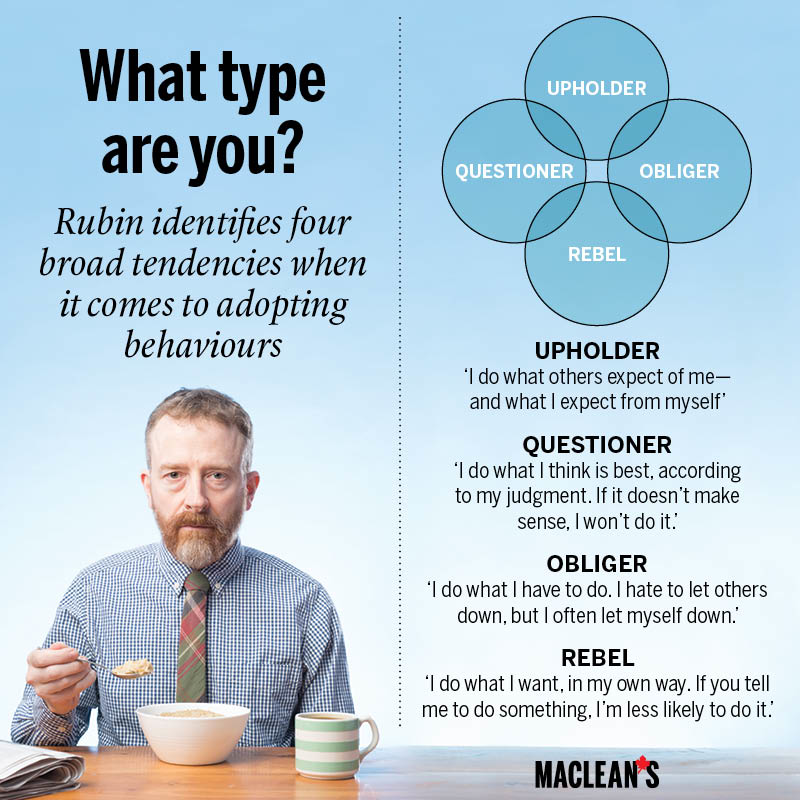

In looking at how we develop routines, she identifies four broad human tendencies in her book. There are “upholders,” such as Rubin herself; she wakes up to a to-do list, knows any expectations of her—whether from other people or herself—and avoids letting anyone down. There are “obligers,” who are motivated by external accountability. “Questioners” respond to expectations, if they make sense based on their own judgement, and “rebels” resist control, even self-control. The iconic line, “Don’t mess with Texas,” Rubin points out, started out as a slogan for an anti-littering campaign. Over five years, visible roadside litter fell by 72 per cent. Texans identified with the slogan. In their own lives, rebels may respond better to an angle that reflects their individualism, instead of, say, being lectured about the benefits of a spin class.

Rubin believes that knowing how you tend to behave better equips you to shape your habits—and, sometimes, to outwit yourself. We may be lovers of familiarity, who enjoy rereading a favourite novel, or novelty-seekers, for whom the same breakfast day after day is anathema. For an abstainer, cutting back on that bad ice-cream habit may require never bringing ice cream into the house, whereas a moderator may be able to take a spoonful or two and put it back in the freezer.

Part of the trick is actually seeing our habits as such. Routine actions can be so ingrained, we continue to take them, even when they don’t make sense. At the University of Southern California, psychology professor Wendy Wood conducted a study in which she gave moviegoers old, stale popcorn that had been kept in plastic bags. Those who didn’t have the habit of eating movie popcorn ate a handful or two, but since it didn’t taste good, they stopped eating. Habitual popcorn eaters at the movies, meanwhile, dug right in. “They told us they didn’t like it, but they still ate it,” says Wood. “The habit was clearly cued by the environment.”

The study also demonstrates the trade-off in habit performance. On the one hand, habits are reliable and consistent, which frees us up to think about more important things. On the other, “You’re not asking yourself, ‘Is this something I want to do?’ ” Wood says. “Instead, you just find yourself doing it.”

A habit has three components, says Charles Duhigg, a New York Times reporter and author of The Power of Habit. There’s the cue, which is the trigger for an automatic behaviour to start. There’s the routine, which is the behaviour itself. Last, there’s the reward, which is how one’s brain learns to latch onto that pattern in the future. “When most people think about changing their habits, they just focus on the behaviour,” he says. “What studies have shown is it’s really diagnosing and understanding the cue and the reward that gives you the ability to shift automatic behaviour.”

Duhigg had a bad habit of going to his work cafeteria every afternoon for a chocolate-chip cookie. The daily snack caused him to put on eight pounds, so he decided to study his craving. It happened consistently around 3 p.m. That was his cue: the time of day. His routine was straightforward. He got up from his desk, went to the cafeteria, grabbed a cookie and chatted with his colleagues while eating it. Figuring out the reward he was seeking took some trial and error. “Is it that I’m hungry, in which case, eating an apple does the job?” he says. “Or a boost of energy, so coffee should work just as well?” Duhigg tried buying a candy bar and eating it at his desk. He tried going to the cafeteria, buying nothing, but socializing as he normally would. It became clear that the reward was the social time. Now, he’ll just get up and chat with a colleague for 10 minutes before going back to his desk. The cookie has become a thing of the past.

One of Rubin’s bad habits was night snacking, so she developed the new habit of brushing her teeth right after dinner. “It signals to your brain, ‘We’re done here. The gates are coming down. The locks are on the doors,’ ” she says. Now the urge to snack at night is gone. The cue to snack has been disrupted by another habit. “People will say, ‘Make healthy choices,’ ” Rubin says. “I would argue: Don’t make healthy choices. Make one choice and then no more choosing.”

And be patient. New habits, on average, take 66 days to form, according to research from University College London. Depending on the person and the habit, it can take months longer. Meanwhile, there are temptations. A mother says her child can’t have a popsicle after soccer practice, but the child convinces her to make this time the exception. With enough persistence, the exception becomes the rule.

William James equated suffering each lapse in a good habit to dropping a ball of string. Every fall undoes enough string to require many turns to wind it back to where it was before. And loopholes come in many forms. There are moral licensing loopholes: giving ourselves permission to eat a bag of chips as a reward for losing pounds. Or false choices, such as avoiding the gym because there are so many emails to catch up on. “We are just masterful advocates for ourselves and why we should be off the hook,” says Rubin, who lists 10 potential loopholes in her book, but adds she discovers more all the time. And yet, she says, by catching ourselves trying to use a loophole, we can choose to reject it. “Just spotting them is enough to disrupt their power.”

Little fixes can make a big difference. Disorder in our lives can act as a “broken window,” Rubin writes in her book, citing the 1980s crime-prevention theory that claimed communities that tolerated little things such as graffitti or the breaking of windows were more likely to attract more serious crimes. So what are the “broken windows” in our everyday lives? It could be letting the laundry pile up at home or having a cluttered desk. Making your bed each morning, Duhigg writes, is correlated with better productivity and an ability to stick to a budget. The bed-making itself doesn’t lead to smarter shopping choices, but it lays the right foundation for other good habits.

The key is not to think about grand, sweeping changes, but rather, small ones. Fogg would say very, very small. Back at Stanford, Fogg used his research to develop the “Tiny Habits” formation by keeping it deliberately simple. It runs counter to the way we think about changing habits. No one tries to meditate for three breaths; it’s often 15 or 30 minutes. Maybe we think aiming big is important because, that way, at least we’ll do half of it. It turns out the exact opposite is true.

To build a habit, Fogg says, you use an existing routine, such as brushing your teeth, as the anchor. That anchor becomes the reminder. Next, you do an incredibly simple version of the target behaviour. If you want to develop the habit of flossing, you make your goal to floss one tooth. That’s it. The habit isn’t learning how to floss, because everyone knows how to do it. The habit, Fogg says, is remembering to do it. Then, the final step is to celebrate instantly. Maybe shout “Victory!” or think of the theme music to Rocky. “What you’re doing is, you’re hacking your emotional state,” says Fogg. “You’re deliberately firing off an emotion right after you floss.” It sounds odd, especially because your fingers are probably messy and your gums could be painful. But, says Fogg, “emotions create habits. The habits that form quickly in our lives have an instant emotional payoff.”

For Tony Stubblebine, a self-described “human potential nerd,” that emotional payoff comes from productivity. It’s the reason he wears the same style of shirt every day. He only buys one type of socks. “I think you have to have a lot of time to dress like [rapper] André 3000,” he says. Very much influenced by Fogg’s research, Stubblebine founded coach.me, an app that promotes developing habits. Users can choose a goal and set up free or paid coaching help—such as reminders, Q&As or a personal coach—and track their progress. Need extra encouragement? A daily check-in from a coach, for example, will cost $15 a week, while phone or video consultations have varying prices depending on the coach. The coach.me app has more than one million users, Stubblebine says, and no habit is too small. That includes flossing, as one journalist from Wired magazine, who hired a flossing coach, found out. “I feel like I want a keynote at the American Dental Association, we’ve helped so many people floss,” Stubblebine says.

Jo Masterson’s My Pocket Coach app offers a similar service. When users choose a goal to lose weight, the app will prompt them with smaller habits to try. Take the stairs, drink water after each meal, or use smaller plates. “We’re simply a tool to help them track their progress and remind them if they get off-track,” says Masterson, who is COO and co-founder of 2Morrow, the parent company. “We’re not trying to be the cue for them.” That’s important—otherwise, says Wood, “what you’re doing is you’re developing a coach habit, not a behaviour habit.”

We all have habits; companies have figured this out. “That’s why every soup can looks the same and is red. Everyone is trying to piggyback on the Campbell’s soup can,” Wood says. “They figured out that shoppers go into stores and just look for the red can, so all the competitors make their cans red to trigger the same habitual buying.”

Similarly, when psychology students at the University of British Columbia used hidden cameras to compare students’ recycling habits in two campus cafeterias—one caf was in a “green building,” the other in the dingy, old student union building—they found those in the former were more likely to recycle.

Convenience has a major influence on our choices. It’s the reason hotels have mini-bars or leave the overpriced chocolate bars on the counter in plain sight. The converse strategy, for individuals, is to make bad choices harder. Regret pushing the snooze button on the alarm clock each morning? Put the alarm clock on the other side of the room. And, no matter the routine, it’s only a habit if it actually sticks. That’s the reason Rubin thinks timed habit changes—the 30-day detoxes or the year without sugar—can be dangerous. “Why a year? And what happens in month 13?” she says. “You need to have a plan for that.”

Rubin identifies four broad tendencies when it comes to adopting behaviours: Upholder, obliger, questioner and rebel.

Upholder: ‘I do what others expect of me—and what I expect from myself’

Obliger: ‘I do what I have to do. I hate to let others down, but I often let myself down.’

Questioner: ‘I do what I think is best, according to my judgment. If it doesn’t make sense, I won’t do it.’

Rebel: ‘I do what I want, in my own way. If you tell me to do something, I’m less likely to do it.’