Last call for bartenders

Singles don’t need bars anymore, and the rest just don’t seem to want to go

Photo Illustration by Sarah MacKinnon and Richard Redditt

Share

The history of many a country can be traced through its watering holes. There’s the Wolf’s Head bar in American Revolution–era Newbursport, Mass., and the Star Tavern in London where plans were hatched for the Great Train Robbery. But as York University professor Christine Sismondo notes in America Walks into a Bar, even the most nondescript bars with no pedigree have had an indelible effect on public life. They bring together strangers from disparate classes, inspiring friendships, spirited conversations and much more.

Tell that to Steve Pauls, who bought the sports bar Monashee’s in 2008, part of a package deal to own the adjacent 30th Street Liquor Store. If Vernon, B.C., locals wanted to stay for a pint or grab a two-four to watch the game at home, he had them covered. But the bar struggled to make a profit. Pauls tried various strategies, including reconfiguring it to give it a nightclub atmosphere on weekends. At first, “We’d be busy from 10 p.m. to 2 a.m.—four hours of steady traffic,” he says. By last year, many weren’t showing up until midnight or 12:30 a.m., leaving Monashee’s only an hour and a half of steady customers. The bar was seeing a six-figure loss every year.

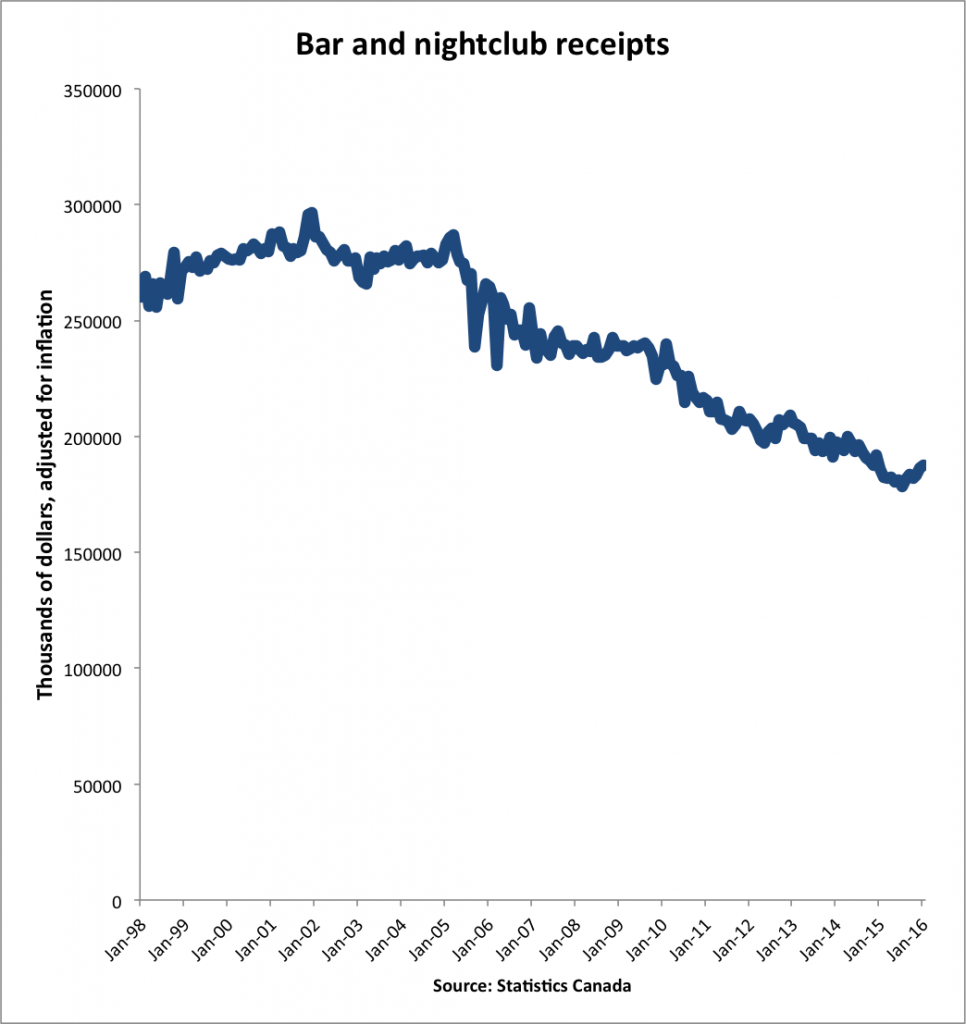

For all the whisky bars staffed by moustachioed hipsters popping up in fashionable districts of Toronto, Vancouver and Montreal, a recession of drinking venues is under way. According to Statistics Canada, revenues for drinking establishments—from taverns to nightclubs to your neighbourhood pub—have declined by more than 35 per cent, in real dollars, since 2001.

And it’s not just the Monashee’s of the world—the barcession, so to speak, has hit legendary venues, too. The iconic Railway Club in Vancouver was put up for sale last year and the Brunswick House, a mainstay in Toronto since 1876, is rumoured to be making way for, of all things, a Boston Pizza.

“The traditional beer hall that I would have attended is going the way of the dodo,” says Geoff Wilson, president of Toronto-based food-service industry consulting firm fsStrategy. One factor: More Canadians seem to want a full dining experience, rather than an excuse to go drinking, he says. “A lot of these taverns have evolved into full-service restaurants.” Another game-changer is the shift in attitude toward drinking and driving, coupled with the fact that minimum legal blood alcohol levels for impaired driving have dropped from 0.08 to 0.05 in several provinces. “Even if it’s just the designated driver not drinking anymore, that’s one out of a party of two or three,” Wilson says. That has an effect on revenue.

Pauls, who came of age spending weekends on Electric Avenue in Calgary, has another theory: the evolution of the cellphone. “These days, with texting and instant messaging, you know what your friends are doing every second of every day,” he says. “Do you really need to sit down with them at the bar for three hours to catch up and talk about life?” Nor do singles need bars to meet new people: Tinder has replaced that with one swipe.

Economics is part of it, too. Since 2004, the price of beer sold at a licensed establishments in Ontario has risen by 32 per cent, while the retail price has increased by only 16 per cent. That could be because of rising labour costs at bars, higher insurance rates and increased rents, but bar owners also pay upwards of 30 per cent more for beer than the rest of us. A customer buying a two-four of Labatt Blue at the Beer Store pays $32.95. A bar owner pays $45.75, and must price that beer even higher to make a profit. “It’s not good value for your money,” Pauls says. “It’s too expensive to go out and drink.”

Hence the popularity of pre-drinking. “People used to say, ‘Let’s meet at the bar,’ ” says James Rilett, vice president, Ontario at Restaurants Canada. “Now they say, ‘Let’s meet at our place and we’ll see whether we go out or not.’ ” More and more, they end up staying in; the bar’s not the only place with a big-screen TV. “Today, if you don’t have a 50-inch TV in your house, you’re living in the Dark Ages,” Pauls says.

Last fall, Monashee’s poured its last pint. Pauls decided the bar was no longer worth it. Instead, he’s using that space to expand his increasingly busy liquor store.