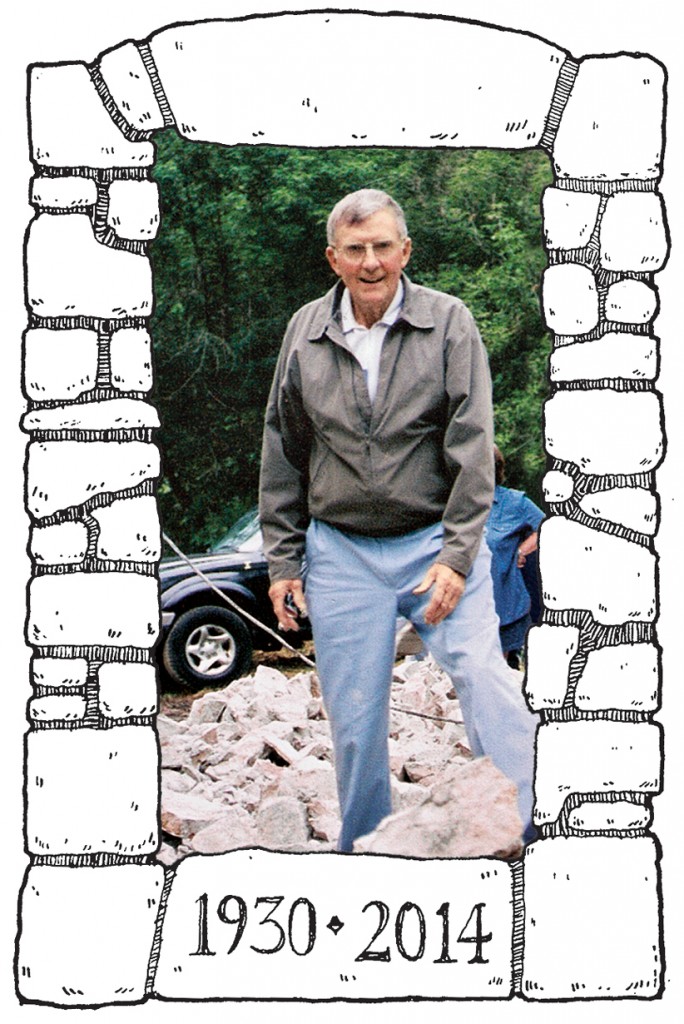

Orval Leslie Ladd, 1930-2014

A natural when it came to fixing and building things, he turned his skills to preserving the history of his beloved hometown

Share

Orval Leslie Ladd was born Sept. 28, 1930, in the village of Lyn, Ont., 64 km northeast of Kingston. He was the youngest of five kids born to Arthur Ladd, who delivered milk from surrounding farms to a nearby processing plant, and Hazel, a homemaker.

Orval Leslie Ladd was born Sept. 28, 1930, in the village of Lyn, Ont., 64 km northeast of Kingston. He was the youngest of five kids born to Arthur Ladd, who delivered milk from surrounding farms to a nearby processing plant, and Hazel, a homemaker.

Orval pitched in early to help with the family business. By 12 he was driving the milk truck. His brother, Lawrence, two years older, also helped. Tragedy struck in 1942 when Arthur accidentally backed the milk truck over Lawrence, then 14, killing him. Orval deeply missed his brother. Even many decades later, recalling the accident brought tears to his eyes.

Orval attended Lyn Public School, the two-room schoolhouse in the town of 1,500. A joke-teller and prankster to his core, one winter night he snuck over to the school. Holding the school bell upside down, he poured water in until the clapper froze solid. The next morning he watched with a smirk as the teacher tried to ring the morning bell.

Orval also had a lead foot. In his teenage years, a local constable often tried to nab him for speeding. But he would hide behind a building or a barn and wait for the police officer to go through and then take off in the other direction, honking at the constable.

In his teens, Orval started dating Pat Clow. They married on Aug. 8, 1953; Orval was 23, Pat 20. Orval built their first house, just prior to the wedding. On Dec. 23, 1955, it burned down. Their first son, Michael, was born four days later. Orval rebuilt on the same spot, and over the years he would build and sell a slew of other houses and cottages in the area.

Orval and Pat raised four children in Lyn. After Michael came Ann, Joan and Peter. The couple’s romance never faded. “He always said that he first knew he was going to marry me when he was in public school and saw me riding to school on this little bicycle that I had. He said I was the cutest thing he’d ever seen” recalls Pat. “And he told me he watched that scene in his mind every night.”

Orval worked as a salesman for Myers Pumps. Despite only having a Grade 8 education, he became Myers’ territory manager for eastern and northern Ontario, and western Quebec. He often racked up to 130,000 km a year travelling for work. While school was not Orval’s thing, he was a natural when it came to figuring out how to fix and build things. His house was stocked with copies of Popular Mechanics. He taught himself electrical work, carpentry and stone masonry. He excelled at them all, says his friend, Rolf Rugge. “He hated anything to do with paperwork. Most of his projects were in his head.”

Orval’s real passion, which ramped up after he retired, was preserving Lyn District history. He loved the village that he called home his entire life. “He’d say, ‘I can’t see chasing a golf ball around a field when I could be doing something more productive,’ ” says Pat. In 1999 as he entered his 70s, Orval, still happiest when covered in mud and mortar, initiated the Lyn Heritage Place Museum, which focused on the town’s original flour mill. Orval did three-quarters of the stone work to create the museum.

Orval, says friend Michael Brown, “always stuck to his guns,” sometimes to the chagrin of the municipal authorities he dealt with. Orval, along with Rolf and Michael, felt Lyn deserved a public war memorial. Council was lacklustre on the notion, but, says Brown, Orval got an article in the local paper extolling the idea. Within days, nearly $10,000 in donations came in. Orval built the base of the Lyn Veteran’s Memorial with stones from the old mill. He was lauded with awards for his heritage work, including the Queen’s Golden Jubilee Medal and Lieutenant Governor’s Ontario Heritage Award. But he hid the medals away. “He was pleased, but he wasn’t one to flaunt them,” says Pat.

On Feb. 7, after helping his son Peter with a remodelling project, Orval went to the old firehouse in Lyn to pick up building materials he was storing there. He arrived home that evening and mumbled something to Pat about getting hit on the head—possibly by the overhead door at the firehall, or the rear hatch on his van. Pat, seeing the swelling on his head, said she was taking him straight to the hospital. He argued he was too dirty to go so she quickly cleaned him up first. Doctors, discovering a brain hemorrhage, transferred him to Kingston, but no one could stop the bleeding. He was 83.