Queen Elizabeth: working mom

But nation caretaking, travelling and meeting people came at the expense of her kids

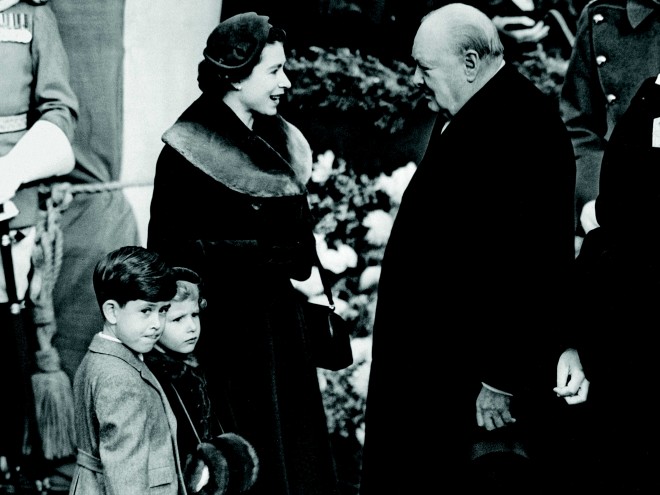

1953: Elizabeth II, Queen of England with Prince Charles and Princess Anne chatting to Sir Winston Churchill (1874 – 1965). (Photo by Central Press/Getty Images)

Share

Interested in more Maclean’s Diamond Jubilee coverage? Take a look at our e-book on the Queen and our special commemorative edition celebrating her 60 years on the throne.

When Queen Elizabeth II was just a young princess, her tutor would address her in an unlikely way: “Gentlemen,” the eccentric Henry Marten would say to her while outlining some concept of constitutional law or history. It may have been by force of habit—Marten had for years been teaching boys at the elite Eton College. Or it might have been a hint of what was to come.

The Queen is a woman, but it’s easy to overlook that fact. Easy to forget that, besides being leader of the Commonwealth, head of state of 16 nations, head of the armed forces and head of the Church of England, she has been or continues to be a daughter, sister, wife, mother, grandmother, great-grandmother. These other roles have always, at least publicly and perhaps rightly so, seemed less important than being the monarch. It’s more natural to think of her meeting with political leaders, taking official tours and sifting daily through government documents than exercising her maternal or feminine instincts.

“If you look at all the actions that the Queen has done, you could easily say she’s been doing a man’s job,” says Robert Finch, dominion chairman of the Monarchist League of Canada. That is no sexist crack: before Elizabeth’s reign, there was a string of four kings—and since the Norman conquest of 1066, only five other females have held the top spot. “In fact, I consider her to be one of the world’s greatest statesmen,” continues Finch. One who just happens to be a woman.

The significance of the Queen’s gender relative to her royal position hasn’t been lost on her grandson William, duke of Cambridge, who has commented on the “enormity of what she’s done” since ascending to the throne as a young woman in 1952. “Stepping into a job which many men thought they could probably do better—it must have been daunting,” he told biographer Robert Hardman, who wrote the recent book Our Queen. “There was extra pressure for her to perform.” As Sally Bedell Smith, author of the newly published Elizabeth the Queen: The Life of a Modern Monarch, has said: “She was a 25-year-old trying to prove herself in a world of men.” According to many observers, the Queen has far exceeded expectations. “Frankly, she does what she feels is right, and I think that’s very impressive,” says William. “She’s been put in some really difficult positions and yet she handles it very well. She’s a huge role model for me. She’s incredible.”

In this way, the Queen has served as a surprising role model for many people around the world. “Here is a woman who literally has given her whole life to service,” says Finch. “We don’t often think of the sacrifices the Queen has made.” She was, after all, one of the first modern working moms—struggling to balance her domestic responsibilities with her professional obligations, all in the public eye. She encountered and overcame chauvinistic notions about the proper place of women in society—her father, for one, was against her participation in the war, and her husband was aghast at her insistence on keeping her last name. In fact, in many ways the Queen has allowed her femaleness to inform her way of reigning—making reformations that would have once seemed outlandish. “And to do [all this] in an era where there’s much scrutiny and questioning of traditional institutions—to carry on diligently for 60 years—is absolutely remarkable,” says Finch.

Even before becoming Queen, Elizabeth had signalled her unwavering commitment to the job above all else during a speech she made at age 21. “I declare before you all that my whole life, whether it be long or short, shall be devoted to your service and the service of our imperial family to which we all belong.” Particularly noteworthy in this speech was her characterization of the 54 independent member states as family. “In her role as head of the Commonwealth, there has been a sense of her being a mother figure to all these diverse nations,” says Carolyn Harris, a Canadian expert on British monarchy and blogger. “That’s a role she has taken very seriously. She has travelled extensively.” In fact, during a recent address to mark the Diamond Jubilee, the Queen remarked that, over the years, she has learned that “the most important contact between nations is usually contact between its people.”

All that mothering of nations—which, taken together, account for nearly one-third of the world’s population, as the Queen also noted—has arguably come at the expense of her own children: Charles, Anne, Andrew and Edward. It’s a painful point that has haunted the Queen since she came into power with two toddlers, and became the public face of working mothers, and eventually a punching bag, too. “She was one of the first women of her social class and of her generation who really had to balance a full-time career and motherhood,” explains Harris. Of course, the Queen had plenty of money and hired help to compensate for her absences, but her challenge is one that still plagues women today. “She endured that [struggle] decades ago. That’s something many of us can relate to; how do you make time for yourself, your kids and your family?” says Finch. The dilemma would have been all the more difficult given the all-encompassing nature of her job. “It’s not one where you can pick up the phone and say, ‘I’m sick today.’ So at the end of the day, her duty to her people came first. And her own family had to come second.”

That the Queen’s profession trumped her husband’s also meant that this was a most modern family. Elizabeth became a female breadwinner long before it was a contemporary social trend. Prince Philip had enjoyed a fulfilling naval career when word arrived that his wife’s father had died in the middle of the night from a blood clot. It was Philip who delivered the news to Elizabeth, but it no doubt was a shock to him, too: “He had to leave his career at the age of 29 to basically support his wife in her position. That was a sacrifice not many men of his social class and generation had to make,” says Harris. Acquiescing to her decisions wasn’t always easy, according to Bedell Smith. When the Queen chose to keep her last name, Windsor, rather than take on Mountbatten, Philip was deeply hurt. “He said he felt like an amoeba. He was the only man who could not pass his name to his children.” (Years later, the name was changed to Mountbatten-Windsor.)

Philip should have known that Elizabeth possessed a strong sense of independence. She had, after all, married him despite the opposition of her parents, who would have preferred she attach herself to a wealthy British aristocrat. For a woman whose life was almost entirely determined for her at birth, the choice to marry whom she preferred rather than whomever was prescribed by her parents was an incredible act of autonomy. “One of the biggest decisions you’ll make in life is choosing your partner, and Elizabeth was adamant that Philip was the man” for her, says Finch. “And it speaks to her judgment because they’ve been married a very long time.” In fact, during her recent jubilee address, the Queen went out of her way to pay homage to her husband for his loyalty and support during her reign. “Prince Philip is, I believe, well known for declining compliments of any kind. But throughout he has been a constant strength and guide.”

The Queen would exhibit her sense of independence many times over the years. During the Second World War, she felt strongly that she too should be participating. “Elizabeth was insistent she wanted to do her bit,” says Harris. Against her father’s wishes, Elizabeth joined the Auxiliary Territorial Service in February 1945, and was registered as No. 230873 Second Subaltern Elizabeth Alexandra Mary Windsor—she had become a mechanic and driver. Historical footage shows her dressed in the same army-issued coveralls and cap as everyone else, reaching into the engine of a military vehicle. “There’s a certain confidence and determination in her character,” continues Harris, “that when she sees a certain course as being right then she’s interested in pursuing that.”

In the years since she became Queen, Elizabeth has met with the sitting British prime minister every Tuesday to discuss the affairs of the country. While the details of those gatherings are never revealed, the Queen has been known to express her views as she sees fit. She was, for example, against the attempted takeover of the Suez Canal, and was furious at the invasion of Grenada ordered by American president Ronald Reagan. She also broke from the tradition of previous sovereigns in attending the funeral of one of her subjects, former prime minister Winston Churchill, in 1965. She has reformed the monarchy by cutting expenses, and increasingly opened up Buckingham Palace to a broad cross-section of society. “She’s very interested in keeping the monarchy a dynamic institution that changes with times while maintaining some of its traditions,” says Harris. She is said to email her grandchildren often.

The Queen’s defiance has been sometimes subtle, too—and has even struck “a feminine chord,” according to Hardman in Our Queen. Whereas previous kings created medals that reward the chivalry, gallantry and excellence of the men who have fought in war, she chose to recognize an entirely different type of virtue: sacrifice. The Elizabeth Cross “is awarded to the families of members of the armed forces who die in the service of the country,” explains Hardman. “Inevitably, it is widows and mothers who tend to wear it. And it is entirely in keeping with the style of the monarch who has created it.”

For a woman who has been pilloried for being a detached mother, a villainous mother-in-law, a cold and stoic Queen, the significance of this gesture cannot be overstated. She might be more maternal than most have been led to believe. She might, in her old age, be seeking the sorority that eluded her previously. She has taken William’s wife, Catherine, duchess of Cambridge, under her wing. She has granted Camilla, the mistress-turned-wife of Charles, a new and personal honour, dame grand cross of the Royal Victorian Order. Having just celebrated her 86th birthday, the Queen may realize her reign is approaching its final days—and she will be replaced not once but twice by men: Charles and William.

And then? Elizabeth, it seems, has set it up so that another female could readily take over. “The lasting legacy of the Queen’s rule will be the reform of the royal succession acts,” says Harris, which will allow the eldest child to inherit the Crown, regardless of the sex of subsequent siblings. “So if the duke and duchess of Cambridge’s first child is a girl, she will ascend to the throne.” And she can thank her great-grandmother for that.