Tracking the CFL’s longest yard

Canadian football’s chief statistician is reconstructing the league’s history, one play at a time

November 8, 2013 – Richmond, BC – Steve Daniel is responsible for keeping track and verifying statistics for the CFL, photographed in his home. Photo by Jimmy Jeong

Share

For decades, the record for most touchdowns scored by any single CFL player in a Grey Cup game was three, a record shared by three players: Red Storey in 1938, Jackie Parker in 1956 and Tom Scott in 1980. Then, in 2011, the record was shattered, not with any superstar performance in that year’s game, but through dogged research of a game played nearly a century earlier, before the days of the forward pass. One long-forgotten member of the Hamilton Tigers, Art Wilson, scored four touchdowns in the 1913 Grey Cup, and he finally got his due.

It was just one in a long line of efforts to set the record book straight by Steve Daniel, the CFL’s statistics guru, who has possibly the league’s loneliest job. In modern professional sports, statistics are invaluable. They are used by coaches and players to compare performances and analyze plays. The numbers also help create storylines about athletes or coaches chasing records in history books. Yet, until a few years ago, the CFL was barely in the statistics game. Front-line data gatherers at each stadium interpreted rulings differently, Grey Cup game reports from decades past didn’t include modern statistical categories such as “tackles,” and something as simple as a roster of the names of every player who ever put on a CFL uniform was incomplete because old game sheets only listed players’ surnames. Working from his home in Richmond, B.C., as the CFL’s top statistician since 2005, Daniel is the sole keeper of the entire league’s statistical history (every touchdown, tackle, sack and catch), a database of numbers he’ll be updating when the Grey Cup gets underway in Regina on Nov. 24. Coaches today rely on Daniel’s numbers to scout such things as how their teams fare on running plays against the Saskatchewan Roughriders, or how often quarterbacks throw interceptions against the Edmonton Eskimos’ defence. “My boss once said to me: ‘The Buffalo Bills of the NFL have three statisticians on their team. We have you, for our league,’ ” Daniel says. “I thought that was a pretty good statistic in itself.”

And it was in his role as chief stat keeper that Daniel helped rediscover Wilson’s record. Playing in front of 2,100 fans at the Hamilton Cricket Grounds a century ago, Wilson’s record day was long lost in newspaper archives. The league’s historian, Larry Robertson, had become aware of old news reports about the feat and, after bringing it to Daniel’s attention, the duo spent months combing through newspaper archives. Among the eight dailies covering the game that day, they found a tangle of conflicting reports for how many touchdowns he scored, a consequence of reporters sitting in the stands without the benefit of television or instant replay. Robertson has an additional theory. “Reporters in those days liked to have a drink or two,” he says. That Grey Cup was a blowout, with Hamilton defeating Toronto 44-2. “I would say, by halftime, half the reporters started to lose interest in who was scoring the points on the field.”

Regardless, drawing from the information they could gather, Daniel and Robertson created a chart to remake what they thought was the most accurate account of the 1913 championship game, including Wilson’s four touchdowns. “Statistics is not just science, it’s not just process,” says Daniel. “It’s interpretation. That’s the key that most people don’t get.” He took their conclusion to the heads of the CFL and the record books were quickly updated. “You are in fact affecting history,” says Daniel. “I think about that all the time.”

Daniel’s dream of being a statistician started in childhood. In his spare time, he’d lie on his bedroom floor, compiling stats from his little-league baseball games. “My dad would yell at me: ‘Do something with your life!’ ” Daniel recalls. After high school, he followed his father’s footsteps into a job at BC Hydro, where he toiled as a manager for 20 years before being laid off in 1994. With one year’s severance pay and his wife’s blessing, Daniel convinced the Portland Trail Blazers professional basketball team to let him compile the team’s statistics in games—for free.

A year later, when the Vancouver Grizzlies joined the NBA, then-general manager Stu Jackson hired Daniel to work with the expansion team. He’d compile the results of every play in practices and games, put them into a database and see which plays were most successful against which teams. “We gave him a nickname,” says Larry Riley, director of scouting with the Golden State Warriors, who previously worked with the Grizzlies. “We called him ‘Numbers.’ And we did it out of respect.”

Even though Daniel had no reputation in the basketball world, he soon found himself sitting at tables among general managers and coaches for the NBA draft. Daniel wasn’t there to measure a player’s heart or character, but he created a mathematical formula to determine a player’s efficiency on the court.

Modern-day sports fans have become obsessed with statistics, and both media and sports managers have caught on to their importance. Billy Beane, the general manager for baseball’s Oakland Athletics, was captivated by overlooked statistics such as “on-base percentage.” He believed he could create a winning club without having to break the bank with all-star players. Beane’s experiments with sports and statistics were captured in the book-turned-movie Moneyball. Meanwhile, Nate Silver, the statistician who correctly predicted the outcomes in all 50 states for the 2012 U.S. election, was recently scooped up by sports-media juggernaut ESPN to use his statistical expertise for data-driven sports analysis. Daniel may not have the name recognition of those two, but he has been employing the same types of strategies since he first entered the NBA.

When the Grizzlies moved from Vancouver to Memphis in 2001, Daniel followed for a few years, but with his family still back in Vancouver, he opted to leave the job and return home. When his former Vancouver colleagues heard he was back in town, they quickly got him a job with the B.C. Lions as a press-box PA announcer.

It was from the sidelines of the 2005 Grey Cup where Daniel came to understand fully the shortcomings of the CFL’s system for gathering stats. As he watched, Anthony Calvillo, the legendary Montreal Alouettes quarterback, threw a pass to Dave Stala. Daniel was ready to announce Stala’s catch over the PA to the 59,000 fans in attendance, but the front-line statistics crew had mistakenly recorded another player, Ben Cahoon, as making the catch. “Cahoon is the all-time leading receiver in the history of Grey Cups,” says Daniel. “And here’s the guy being credited for a catch he didn’t make.”

Given the conflicting information, Daniel chose to announce what the stat crew reported about Cahoon making the catch. But he made note of the error. The next day, he was promoted to chief number cruncher for the B.C. Lions and set about filling the many gaps in the club’s history books—no easy task since, according to club folklore, Vancouver stock promoter Murray Pezim had thrown all the records into a garbage bin when he bought the team in 1990 because he wanted the team’s primary focus to be selling tickets. “So I started rebuilding,” Daniel says.

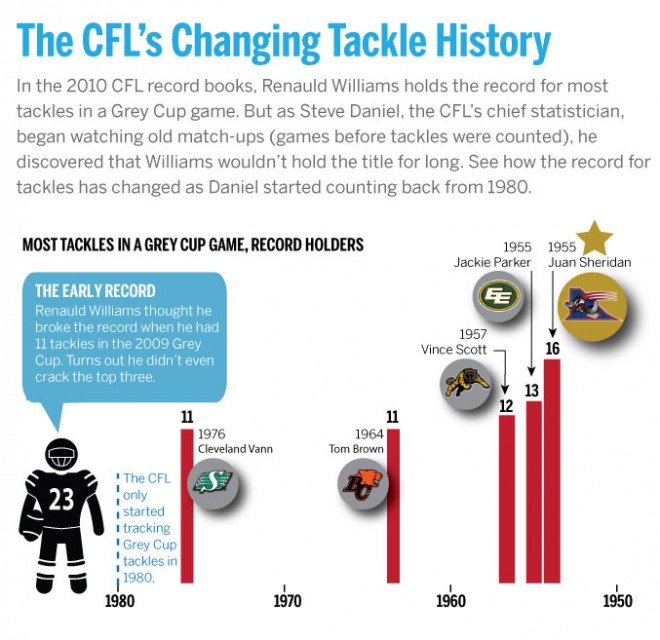

When the CFL saw how Daniel revamped the Lions’ statistics database, the league hired him to standardize every team’s numbers. One of Daniel’s very first orders of business in his new role was to go into the Grey Cup history books and reverse that one catch by Cahoon, taking the receiving yards away from the record holder and giving them to the rightful recipient. Then he started digging deeper. “To me, a player who played in the 1956 season is every bit as important as one playing now,” Daniel says. To that end, Daniel has since gone back and watched every Grey Cup game from when it was first televised in 1952 to update every number, including “tackles,” which weren’t officially tallied until 1980. “So now, if someone asks me the record for most tackles in a Grey Cup game, I can tell you it was Juan Sheridan [with the Montreal Alouettes] in 1955, with 16.” Prior to Daniel’s research, that record belonged to Saskatchewan’s Renauld Williams from 2009. During the CFL season, Daniel has little time to focus on the history books. Fans expect numbers updated in real time on their smartphones, something stats crews at every stadium collecting data can provide. Even with his promotion, Daniel remains as the stats crew chief at all Lions home games. “It’s no fun just sitting in your office watching TV,” he says. But the 56-year-old will diligently watch every single play afterward—even if the game was boring or a blowout—to make sure there were no mistakes on his part or that of the other stats crews gathering info for him. “He’s a lens on every game, and he’s our sole point of end accountability for corrections,” says Kevin McDonald, vice-president of football operations for the CFL. “Steve is the keeper of our information. It’s a pretty big responsibility.”

During the CFL season, Daniel has little time to focus on the history books. Fans expect numbers updated in real time on their smartphones, something stats crews at every stadium collecting data can provide. Even with his promotion, Daniel remains as the stats crew chief at all Lions home games. “It’s no fun just sitting in your office watching TV,” he says. But the 56-year-old will diligently watch every single play afterward—even if the game was boring or a blowout—to make sure there were no mistakes on his part or that of the other stats crews gathering info for him. “He’s a lens on every game, and he’s our sole point of end accountability for corrections,” says Kevin McDonald, vice-president of football operations for the CFL. “Steve is the keeper of our information. It’s a pretty big responsibility.”

And yet, numbers can only go so far. They don’t capture the person off the field: his character, background or history. Since Wilson wasn’t a star player and never received much attention in the press, one mystery still largely eludes Daniel and CFL historians: Who, exactly, was Art Wilson?