What writing 500 obituaries taught us about living

Maclean’s is closing the door on The End, our beloved back-page obit. Before it goes, we asked writer Michael Friscolanti to read through 12 years worth and reflect on the lessons within.

Share

John Richard Ferguson was a corporate lawyer in Washington, D.C., but a big chunk of his heart belonged to Canada—to the crystalline waters of northwest British Columbia, to be specific. Every September, Ferguson spent cherished vacations with friends and family in B.C.’s gorgeous wilderness, fly-fishing for trophy steelhead. In the late-1980s, he even helped launch the Babine River Foundation, an advocacy group that, to this day, fights to protect one of the province’s most pristine bodies of water.

On Sept. 18, 2007, Ferguson was heading out for another day of fishing when he struck up a chat with a lodge employee. She told him about her father, another avid outdoorsman, who had recently died at home in his bed, surrounded by family. “It’s seldom given to a man to choose how he leaves this world,” Ferguson said, after hearing the woman’s story. “But given the choice, I would want to die with a fly rod in my hand and a steelhead on my line.”

That afternoon, the 73-year-old was up to his knees in the Kispiox River, reeling in yet another feisty steelhead. He died moments later, the victim of a massive heart attack.

I wrote about John Ferguson’s very full life on the back page of Maclean’s, in a regular feature affectionately dubbed “The End.” Although I pieced together many obituaries over the years (nearly 20, by my count), his was unforgettable: the rare person who left this life exactly as he’d wished. If only everyone were so fortunate—and yes, fortunate is the right word.

RELATED: Ignore the fear-mongering. Life is good, and getting longer.

I reread that article over the past few days, along with hundreds of other obits published in Maclean’s since November 2005, when the weekly feature first appeared. Why? After 12 years and 492 entries, we’ve reached the end of The End. Beginning in 2018, the back page of the magazine will no longer tell the touching story of a life lost. Nothing lasts forever, after all—as these articles so eloquently reinforced, week after week, year after year.

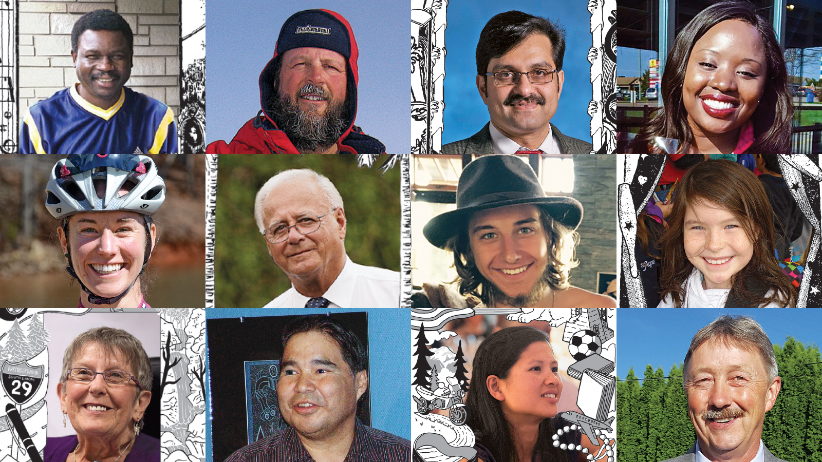

Loyal readers may be sad to learn of this sudden passing. For many subscribers, The End was the first page they turned to, a heartfelt window into a unique yet everyday person. Rarely was the subject an A-list celebrity or political big shot; they were “ordinary” men and women, usually Canadian, whose biographies resonated because they resembled our own. Mothers, fathers, sons, daughters. Plumbers, firefighters, loggers, cooks.

No two narratives were quite the same. One week, it was a master sword-swallower who succumbed to throat cancer; the next, a selfless nurse who refused to flee her burning house without her three beloved dogs. Most contained a poignant or ironic twist. The former manager of Montreal’s Mount Royal Cemetery, who asked to be cremated because he wanted to save space at the property he loved. The plumber who bought a Harley-Davidson after his wife died of cancer because riding helped ease the pain, only to be killed in a horrific crash. The prairie boy so obsessed with the ocean that he built a ship in his Saskatchewan backyard, then drowned when he finally took it to sea.

Yet as singular as each story was—woven together with the detailed memories of those left behind—the collection as a whole says as much about ourselves as it does about the dead. Read enough of those archived obituaries, and you’ll discover them soon enough: the common threads of a life well-lived.

Here’s what I learned.

Find love, if possible, and follow that love wherever it leads. To be loved—by partners, by children, by friends and family—is life’s greatest privilege, by every measure. Glen and Dorothy Baker certainly knew that. A couple for 60 years, they were both admitted to St. Thomas-Elgin General Hospital in November 2006, suffering from various ailments. As the couple’s conditions deteriorated, staff wheeled their beds into the same room so they could lie side by side, holding hands. Dorothy passed away first, Glen two hours later. “They were totally faithful to each other,” said their only daughter. “But in death they didn’t part—that vow they didn’t keep.”

RELATED: Psychiatrist George Vaillant on secrets to a long life and a bigger salary

Be yourself, whoever that is. Those who enjoy life to the fullest—who find happiness in what they do—follow their own path, not someone else’s. Many people featured in The End could never be tied down, bouncing from place to place, urge to urge. “I am where I am because I am,” wrote Graeme Loader (1989-2014), an Ontario photographer and cyclist, who was run over by an SUV while biking across the country for charity. Others found bliss in routine and familiarity, like Nicolas Huberdeau (1959-2009). A Manitoba dairy farmer, he could identify each of his cows by their spots—and until the day he died of exposure to the cold, he forever regretted shutting down the business. Asked once what he would do if he ever won the lottery, Huberdeau didn’t hesitate: “Buy back my cows.”

When the bell tolls, money really does mean nothing. The reaper doesn’t accept bribes. Yousif Youkhana (1949-2006) summed it up best. A once-successful entrepreneur in his home country of Iraq, he fled to Canada as a refugee, where he struggled to find work and was later killed during an altercation outside a Bingo hall. “As long as you’re safe and you eat bread from God, that’s all you need,” he would often say.

Spend some quality time watching Hockey Night in Canada. It’s good for the soul, apparently. And a cheap date.

RELATED: The sorrowful line between childhood hijinks and tragedy

Don’t feel sorry for yourself (and if you must, keep it short). Jacob Whitney (1992-2012) sure didn’t wallow in self-pity. Diagnosed at 12 with flesh-eating disease that annihilated his right leg, he spent two years teaching himself to walk—never once letting his mother park in a handicap spot. “There is someone who deserves it more,” he would tell her. When cancer forced doctors to amputate her right arm, Sophie Dwosh (1973-2013) had no time to be angry, either; a mother of three, she proceeded to teach herself to do everything left-handed, from writing to cooking, until the cancer ultimately won. “She could change the diaper of a squirming toddler with one arm,” her husband laughed.

More than anything else, these beautiful stories made us contemplate our own stories. Am I living as I should? Is there more I need to do, not just for myself, but for others? Have I left things better than I found them? If the end comes today, what would people say about me?

John Richard Ferguson knew who he loved and what he loved—and exactly where he hoped to be during his final seconds. Do you?