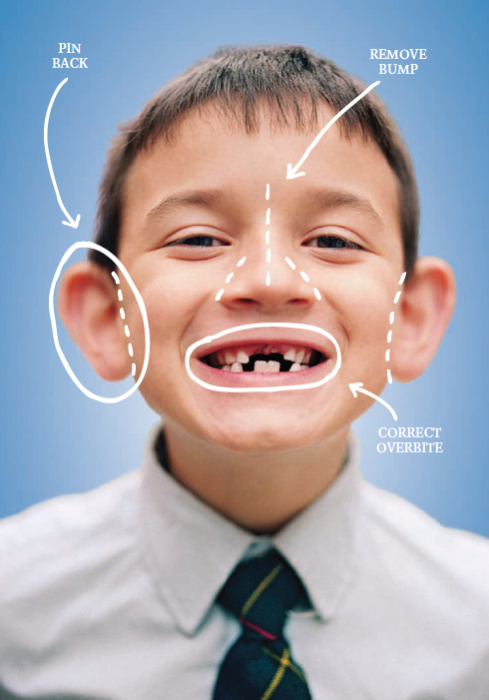

Plastic surgery: Where do parents draw the line?

Corrective procedures can’t guarantee an end to bullying

Share

Kelly Jarvis still remembers being called buck-toothed as a kid. The North Vancouver mother of two had a severe overbite that didn’t get fixed until Grade 8. Even after she got rid of her braces, the insults continued. “It really bothered me,” says Jarvis. “People still teased me about how my teeth were before.”

It’s a fate she wanted to spare her son, Adam, which is partly why she had him start two-phase orthodontic treatment at the age of 7. Now, at 10, his overbite is already corrected despite the fact that he only has eight adult teeth.

In the two-phase method, kids as young as 5 wear dental appliances for a year, before switching to retainers for three or four years, until all their baby teeth fall out. Then they have regular braces for at least one more year.

The treatment is not without controversy. A study by the University of North Carolina that followed 166 children over a 10-year period found that only in very few cases, where there is a severe under- or overbite, are two phases necessary. Most of the research concludes that it is more expensive, takes longer and has the same outcomes as the traditional one-phase method. But proponents argue that the main benefit, in many cases, is a boost to a child’s self-esteem that may help to fend off bullying.

In Adam’s case, Jarvis and their family dentist felt his overbite was large enough to warrant early intervention. Without it, his protuding teeth were at risk of getting knocked around and of chipping. But beyond that, Jarvis was concerned by the impact of teasing on her son, whom she describes as sensitive. “I thought, to be able to take any further issue away from him would be great.”

Jarvis is not alone in her worry. Bullying has been thrust into the spotlight in recent years, with everything from cyberstalking to teen suicide making international headlines. Parents are more concerned than ever about their children’s emotional well-being, and, to that end, some are turning to cosmetic procedures.

According to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, there were 230,617 teen cosmetic procedures, ranging from Botox to breast implants, in 2011. Rhinoplasty (nose jobs) were the most popular surgery, with more than 33,000 procedures, followed by 14,371 breast reductions for males. Comparable data for Canada are not available.

In August 2012, 14-year-old Nadia Ilse of Georgia attracted worldwide attention when she underwent plastic surgery to pin her ears back, reduce the size of her nose and alter her chin. The operation, worth approximately $40,000, was paid for by the Little Baby Face Foundation—a charity that provides corrective surgery to kids with facial deformities—and was the subject of a CNN documentary by Dr. Sanjay Gupta. At the outset, Ilse only wanted the otoplasty (ear-reshaping surgery), a procedure that is relatively common for children and, in Ontario, is covered under the provincial health plan for those aged 18 and under. She was tired of being tormented by classmates for her “elephant ears.”

But after meeting the teen, Dr. Thomas Romo, surgeon and founder of Little Baby Face Foundation, suggested changing her other facial features to get a better overall result. In the footage, Gupta is clearly uneasy about this, asking, “She never talked about the nose or the chin before, right?”

Still, when looking at before and after photographs, it’s hard to argue that her ears don’t look better post-op. “I look beautiful,” Ilse told CNN. “This is exactly what I wanted.”

Months earlier, Nicolette Taylor, 13, of Long Island, N.Y., was featured on ABC’s Nightline after getting a nose job to ward off constant name-calling, particularly online. Her father, Rob, told ABC he stood by her decision. “You send them to a good school, you’d buy them shoes. You’d get them braces, which we did. It’s that kind of thing,” he said.

But where do parents draw the line? And at what point are practitioners, be they orthodontists or plastic surgeons, fostering and capitalizing on their fears?

Andrew Miller is a New Jersey plastic surgeon who says about 25 per cent of his business comes from adolescents. In a blog entry posted to his clinic’s website in January, he describes how children as young as 6 get picked on for their prominent ears. Otoplasty “helps build the confidence that is needed to flourish in society,” he says. “It creates the courage and ability to fit in that everyone desires and deserves.”

A similar post by Toronto physician Oakley Smith cites a study out of Britain’s University Hospital of North Staffordshire that claims otoplasty resulted in a reduction or elimination of bullying in 100 per cent of surgeries performed on children aged 5 to 16. Of the children in the study, 97 per cent also reported an increase in happiness, and 92 per cent, a boost in self-confidence.

A similar post by Toronto physician Oakley Smith cites a study out of Britain’s University Hospital of North Staffordshire that claims otoplasty resulted in a reduction or elimination of bullying in 100 per cent of surgeries performed on children aged 5 to 16. Of the children in the study, 97 per cent also reported an increase in happiness, and 92 per cent, a boost in self-confidence.

Most of the procedures Smith performs are nose jobs, a third of which are entirely cosmetic; the remainder are either reconstructive or a blend of the two. He says patients are getting younger and younger and estimates that 10 per cent of his business comes from teenagers.

One of them, Sandra Annan, 18, had her nose altered two years ago in the summer between Grades 11 and 12. Annan had a deviated septum she needed corrected, but decided to have cosmetic work done at the same time to get rid of the bump on her nose.

“When I was younger, I didn’t have great self-esteem. I felt like it didn’t complement my face very well,” says Annan, sitting in a study room at the University of Toronto. She endured teasing in middle school and high school, and recalls an anonymous Facebook account that posted nasty comments onto her profile and those of her friends. Although Annan wanted her nose “straightened,” she didn’t want it to look unnatural, she says. Prior to seeing Smith, she consulted with another plastic surgeon who suggested making more changes than she was comfortable with. “I did not want people to say, ‘Oh my God, you got a nose job,’ ” she explains. Afterward, she says she liked her new nose but didn’t feel all that different.

Smith says that before agreeing to perform purely aesthetic surgery on younger clients, he needs to determine whether or not they are mature enough. “It forces the surgeon to confront what is appropriate and inappropriate,” he says.

The former president of the British Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons argues that for a doctor to even suggest a cosmetic procedure as a solution to bullying is inappropriate. “That, to me, sounds like drumming up business rather than caring for the children,” says Fazel Fatah. “If a child is not teased and you just suppose they may be teased and subject them to treatment that is costly and unnecessary, it is just unethical.”

Fatah, who supports a full ban on advertising plastic surgery in public spaces, says if families come forward because a child is getting harassed, the pros and cons must be weighed carefully. “Children should not be put in an environment where they are encouraged to have plastic surgery. They should be protected and they should be counselled, even if they come forward, unless there is an absolute need.”

Then there’s the matter of how well a superficial solution such as cosmetic work or early braces stands up to a problem as complex as bullying.

Both Miller and Smith believe that well-executed plastic surgery can make a dramatic difference in a young person’s life. “If you do a good job and have a successful result, you are clearly benefiting that person,” says Smith. “Their personality changes, they’re more confident, they just blossom.”

But they might still get picked on, says Vivian Diller, a clinical psychologist in New York. “Bullying isn’t that rational. There are smart boys who get bullied, or popular girls, or rich girls who are also targets, so the notion that you can change someone’s appearance to avoid bullying is something that you don’t want to assume.”

Diller has seen patients on both ends of the spectrum. One woman, who had her breasts reduced as a teenager after being teased and having difficulty playing sports, says it was the best decision of her life. But another, who got her nose done while in high school, became extremely depressed—she continued to be taunted by peers and spent years changing other parts of her face, eventually developing anorexia. “As we looked a little further, we realized it wasn’t really about her nose,” says Diller.

She implores teens to think long and hard about making a permanent change to their bodies, and she wants parents to know that trying to take away their children’s pain with a cosmetic fix is not always the healthiest option.

This trend, she says, is sending out a very disturbing message that kids need to conform to a physical ideal if they want to fit in. “There’s an ‘ick factor’ in putting the responsibility on the victim to alter something about themselves rather than . . . encouraging greater tolerance of differences among teens.”