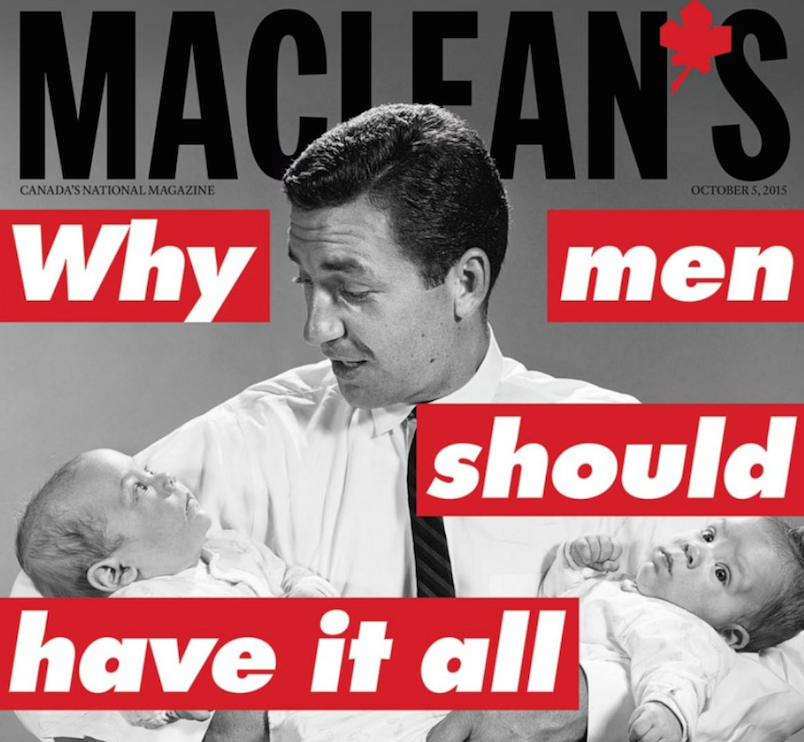

Why men can’t have it all

The case for men’s liberation—and why it matters to women.

Father carrying happy baby girl in park

Share

Andrew Moravcsik would seem an unlikely revolutionary. But the professor of politics and international affairs at Princeton University became a radical outlier this month when he shared his account of being the “lead parent” to his two sons, and a devoted beta husband to his alpha wife. In “Why I put my wife’s career first,” published in The Atlantic, Moravcsik writes of “being on the front lines of everyday life”—getting his children out of the house in the morning, taking them to appointments, being the parent “who drops everything in a crisis.” It was an accommodation he willingly made, he says. His wife has the bigger job; she’s rarely home for more than a couple of dinners a week. His wife will be familiar to many: Anne-Marie Slaughter, a dean of law, and director of policy planning for the State Department under Hillary Clinton, who made a huge splash with her 2012 article, also in the pages of The Atlantic, titled “Why women still can’t have it all.”

Moravcsik’s account, in some ways, was a familiar one, echoing the frustrations voiced by women and overwhelmed heroines of mom-lit classics such as Allison Pearson’s I Don’t Know How She Does It: “Juggling caring and career leaves me feeling that I am doing a bad job as both a parent and a professional,” he wrote, admitting family sacrifices have “unavoidably taken a toll on my professional productivity.” But he also made an admission rarely heard in discussions of work-family trade-offs—the immense satisfaction he got from caring for his children. “Despite many days of weariness, I would never give up being ‘the One’—the parent my child trusted to help master his first stage role, the parent who shared my child’s wonder at his first musical composition, the parent my boys called for when they needed comfort in the night,” he writes.

Moravcsik is something of a rarity as a professional male voice who doesn’t fill a Mr. Mom cliché, but supports a more professionally successful wife—and navigates the tensions surrounding work-family balance that have typically been debated by women in an endless loop for decades.

But he is becoming less of a rarity, as a growing number of male voices weigh in. In “What Ruth Bader Ginsburg taught me about being a stay-at-home dad,” also in The Atlantic, lawyer Ryan Park described leaving a coveted clerkship with the U.S. Supreme Court judge to care for his daughter while his wife returned to her medical residency. CNN journalist Josh Levs published All In: How Our Work-First Culture Fails Dads, Families, and Businesses—And How We Can Fix It Together, a memoir-cum-social policy book about the challenges facing fathers, whose title echoed Sheryl Sandberg’s female call to action, Lean In. Plumbing the frictions within the traditional breadwinner role is also explored in the forthcoming All Out: A Father and Son Confront the Hard Truths that Made Them Better Men, written by CTV news anchor Kevin Newman and his son, Alex. Kevin lost his American network anchor job at the same time Alex came out as gay; the experience forced a personal re-examination of the sacrifices he’d made for his career, and the things he’d given up, Kevin writes: “To become the father my son deserved, I had to re-examine my core beliefs about masculinity.”

At the same time, we are undeniably in the midst of a modern dad moment—from Justin Trudeau’s baby juggling and Barack Obama’s clear affection for Sasha and Malia to Joe Biden speaking emotionally about his late son Beau. Dads are cool—telegraphed in obsessive coverage of Brad Pitt travelling with his entourage of offspring and Kanye West carrying his daughter around New York Fashion Week. We’re witnessing high-profile men who acknowledge a home life, a personal self; their dadhood only burnishes their professional identities.

The modern model dad speaks to a rejection of the distant man in the grey flannel suit—the Don Draper dad—and a desire for an involved, emotionally open caregiver. But, as the voices expressing frustration with the constraints of their role make clear, there’s no system in place to support that kind of real-life father. Dads who take paternity leave face a stigma at work, and are penalized financially. The daddy track, like the mommy track, comes at a cost. Accommodations like flex time are framed as a women’s issue and extended—when they are —to mothers, almost never fathers. It took Levs filing a lawsuit against his employer to be granted leave to look after his three children after his wife developed severe pre-eclampsia after an emergency C-section. In the work-life question, there is a pre-scripted role for men, and it doesn’t leave room for a robust domestic life.

Related reading: Anne Kingston on the no-baby boom

The fault lines are captured in Anne-Marie Slaughter’s new book Unfinished Business: Women, Men, Work, Family, a follow-up to her Atlantic cover story in which she wrote of stepping down from a job she loved at the State Department to return to work as a law professor because she missed her husband and two sons. The admission that a woman so successful, with so many supports, couldn’t achieve work-life balance caused a sensation.

Now Slaughter turns her attention to the missing pieces of the feminist revolution: men. Twenty per cent of responses to the Atlantic article came from men, Slaughter tells Maclean’s. “Many of them said, ‘You think we have it all. But we’re as stuck in gender roles defined by social expectation as women used to be. I would love to be the primary caregiver; I would love to spend more time with children. But if I do it, not only do women think I’m not committed to career, they’re not sure what kind of man I am.”

The “unfinished business” of the title is in part about the need to re-evaluate caregiving, socially and economically—a decades-old conundrum we still haven’t solved since wives and mothers entered the workforce. But, more important, it’s what Slaughter calls “the second half of the women’s liberation movement,” for men to be liberated from the sort of gender stereotypes that limited women. Daughters are being raised with more life paths than sons, Slaughter writes. They’re told they can have that ever-elusive “all”—work and family; boys are handed the traditional messaging of the masculine-breadwinner model.

Slaughter’s words are destined again to resonate with a large audience, just as Betty Friedan’s The Feminist Mystique did in the 1960s. The “women’s movement” was the result of a congruence of seismic forces—economic, social, medical (the arrival of the Pill). Fifty years later, that moment may finally be here for men.

Slaughter’s call for a “men’s liberation” is not new. In his book The Masculine Mystique,” a “manifesto for men” published in 1995, lawyer Andrew Kimbrell made a similar case, arguing that social changes wrought by the Industrial Revolution more than 150 years earlier had put in place systems that reduced men and women to machines whose only concern is to work and turn out more products. The resulting “masculine mystique”—competitive, aggressive, insensitive— that defines the ethos of the working world, as well as male identity, was as insidious as the “feminine mystique,” Kimbrell argued. It was damaging to men in their relations with women, their children and other men.

Related reading: Sheryl Sandberg’s cosmic ‘Lean In’ moment

Kimbrell’s book, obviously, didn’t incite revolution. But two decades later, economic and social shifts have created a more receptive climate. We’ve seen the two-income family become a middle-class norm. According to recent StatsCan data, 69 per cent of “couple families” with at least one child under 16 years of age had two working parents in 2014, up from 36 per cent in 1976. The share of couple families with a single-earner had declined to 27 per cent.

Globalization, too, has tipped the balance for female involvement in the economy; a shift from manufacturing to female-dominated service sectors as well as a record number of women in professional schools has seen women increasingly outearning their husbands, a trend charted in high-profile books like Liza Mundy’s The Richer Sex: How the New Majority of Female Breadwinners is Transforming Sex, Love and Family, and Hanna Rosin’s The End of Men: And the Rise of Women. Another revolution, this one digital, is recalibrating the economy and, with it, male-female relations. Employee entitlements taken for granted a half-century ago—guaranteed jobs, a pension—no longer exist. The instability of work has made both sexes more dependent on each other; it’s all hands on deck.

Social shifts have been equally profound, among them increased male participation in childbirth—from attending birthing classes to being the coaches in the delivery room. Nor does that involvement stop as their children grow. According to StatsCan, fathers spend, on average, 19 more minutes a day with their families than in the mid-1980s. In 2008, the Families and Work Institute found that 60 per cent of American fathers polled reported conflicts between work and home life, close to double the number in 1977.

The legalization of gay marriage—and with it the increasing visibility of same-sex parenting—has also blurred default gender roles. The cover of the current Architectural Digest features Nate Berkus, Oprah’s decorator, with his decorator husband, Jeremiah Brent, proudly holding their baby daughter. There’s no traditional default “lead parent” in gay marriages, and the uptick in non-traditional unions has shifted the cultural baseline.

One response to all of these changes has been hand-wringing about the besieged state of manhood, as seen in Susan Faludi’s 1999 book, Stiffed: The Betrayal of the American Man. But a new generation of fathers is reframing that debate, arguing that manhood isn’t under attack but in need of a new definition that finally reflects what men actually want.

If ordinary men are not having that conversation in a political arena, they are online, on dad blogs, forums like Daddit, and summits like Dads 2.0, a three-day event discussing everything from paternity leave to new thinking about what it is to be a man. The event, launched in 2012, was encouraged by women, co-founder Doug French tells Maclean’s: “As long as dads were not treated seriously as parents, not only was that bad for dad—but it also put an unfair burden on moms.”

What we’re seeing is gender catch-up, says Stephen Marche, a Canadian author who wrote “Manifesto of the new fatherhood” for Esquire. A father of two, he is currently writing a book on the state of men and women in the 21st century: “Gender has preoccupied our thinking for 50 years now, but we’ve only thought through half of the equation,” he says in an interview. “There is no academic sociology on masculinity, which is bizarre,” Marche says. “People have written about it. But compared to the amount of work on femininity, we’re 50 years behind.”

Marche identifies an inherent paradox: “Part of the reason masculinity is marginal is because thinking about masculinity is unmasculine,” he says. “Asking yourself what it is to be a man is itself not part of what it is to be a man.” Fatherhood is one part of masculinity that has no complications to it, says Marche, who notes all of his friends with kids—“from the playboys to the geeks”—define themselves as fathers first. Marche says he goes to the playground with his kids: “It’s all dads there.” Studies suggest family life can be more fulfilling for men than work: Slaughter cites a 2013 Pew Research study that found 60 per cent of men described their child care hours as “very meaningful”; only 33 per cent of men said the same about their paid work. On a broader scale, Marche defines engaged fathers as “a vital social good,” citing a 2014 Harvard study that looked at 40 million households and found the presence of a father in the home is a better correlate for success than schooling. “To underrate the value of fathers is a big mistake,” he says.

It’s not all sociological; neuroscience has identified the “daddy” brain, finding men acquire additional neurons after having children. A 2014 study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found dads’ brains can switch between a network geared toward social bonding and vigilance and one designed for planning and thinking.

Related reading: Inside the daddy wars

There’s also a growing recognition that dads, particularly younger ones, represent an untapped market. A June 2015 story in Marketing magazine noted that dads spend more on domestic purchases and are more brand loyal than moms. Kimberly-Clark felt the wrath of millions of fathers when it ran a commercial for Huggies diapers that played on the stereotype of the bumbling dad. The company showed up at Dad 2.0 to apologize. That the ads aired during the last Super Bowl—once a showcase for beer ads and their bevy of attractive female models—told the tale. Dove Men+Care, a product line courting the dad market, ran an ad for its deodorant and shampoo with the tagline, “What makes a man stronger? Showing that he cares.”

But if marketers and neurologists are adapting to the modern dad, the rest of the world has been much slower. Paternity leave is a case in point. Rarely used, it’s an indicator of the value we assign paternal labour. “You don’t see a chorus of men asking for paternity leave,” says Marche. In Canada, one in 10 men take it. Stigma surrounds it, according to a 2013 Rotman School of Business study.

Yet it’s vital to domestic equality. Cornell University economist Ankita Patnaik charted the experience in Quebec, which greatly expanded paid leave entitlements in 2006 with a “use it or lose it” five weeks for fathers. Patnaik documented a sharp and significant increase in paternal participation—up to 80 per cent in 2010. She also found that fathers who were eligible for the program increased their time cooking and shopping, while mothers reported more time in paid employment. Slaughter points to emerging legal challenges, like the one Levs filed, and this week the New York Times reported men suing for paternity leave on ground of discrimination. Men who take pat leave are claiming that snide remarks about being Mr. Mom creates a hostile work environment, Slaughter points out. “That was one of the big legal tools women in the ’60s and ’70s used.”

Culturally we’re watching a fascinating tableaux of gender-bending masculinity. In fashion, there’s the man bun, designer Rick Owens heels for men and the arrival of the lumbersexual, a beard-sporting, flannel-wearing, unapologetically sensitive man. At the same time, there’s 50 Shades of Grey, with its dominating, controlling, unemotive billionaire character, a cartoon— the last gasp of a masculinity that’s giving way to a more complex, whole reality.

Still, entrenched attitudinal and structural inequities remain. Slaughter points to the Oscar-winning 1979 movie Kramer vs Kramer, about a father who’s a primary caregiver to his son. Thirty-six years later, only eight per cent of Americans feel their children are better with dads at home; over half say they’re better off with their mothers.

“Children don’t need their mothers more than other loving adults in their lives,” Slaughter writes in her book, yet men are routinely told they’re not equipped. Newman writes of feeling incompetent when his son was born; whenever the baby cried when he held him, “instant experts” swept the baby away. Two decades later not all that much has changed. The New York Times parenting blog is called “Motherlode.” (A more apt name might be “The Parent Trap.”) We still talk about a father “babysitting” his child, or being “Mr. Mom.” (Slaughter prefers “lead parent, anchor parent or full-time parent.”)

Slaughter calls for women to get over the Prince Charming construct of masculinity that requires partners be older, taller, richer: “We have to find and embrace an image of a man who can care for children; earn less than we do; have his own ideas about how to organize kitchens, lessons, and trips; and still be fully sexy and attractive as a man,” she writes.

The larger barrier to fathers participating fully is structural, Slaughter argues, stemming from the cultural and economic devaluing of caregiving, which has also resulted in a female underclass of caregivers. Why don’t we ask young men how they plan to achieve work-family balance, the way we do women? “We need to refer to CEOs as working fathers, the same way we refer to working mothers,” she tells Maclean’s.

Slaughter isn’t the first to call for a re-evaluation of “caring labour,” a term coined by American economist Nancy Folbre. It’s only when caregiving has quantifiable economic value that masculinity as we know it will be expanded to include caregiving attributes. Possible structural changes incude making household labour part of GDP; Slaughter notes a new study, about to be announced by Melinda Gates, will quantify the value of domestic work. Caring labour is not just physical labour, she says; it’s the shaping of another human being, be it a child or an adult: “When you do it in the workplace it’s called management or leadership. It’s investing in others.” Her own husband wrote of being shunned, and being left out by mothers. The response to his article has been remarkable, says Slaughter: “He’s getting steady, steady emails and Facebook posts from other men who are telling one story after another. They’re thanking him, particularly younger academic men and men saying, ‘I’ve made the same choice.’ They say, ‘It’s been great for me but I face discrimination in all sorts of ways.’ ” Interestingly they’re raising an issue no one is talking about, says Slaughter. “Men are saying, ‘When I am a primary caregiver, I can’t hang out with moms because their husbands don’t like it—they say it’s one thing if my wife hangs out with other moms, it’s another if she’s having coffee with a man. It’s a threat.’ ” She waves it off. “We heard similar talk in the ’70s when women found their husbands working with young doctors and going on business trips with women. “But we got past it then, we can get past it now.”

The glimpse into the Slaughter-Moravcsik household, as privileged as it may be, offers greater insights into the complexity of work-family balance than a thousand how-tos. It’s similar to another behind-the-scenes look we had after the sudden death earlier this year of Sheryl Sandberg’s husband, Dave Goldberg, a Silicon Valley entrepreneur. At his funeral, five separate eulogies honoured Goldberg as a friend, a dad, and a husband. Very little of what they said was about business. Sandberg’s Facebook post about the grief of losing her partner in all things was a poignant revelation of the other half of the Lean In story: What it took to allow a Sheryl Sandberg to flourish was an involved, active husband with an ambitious career of his own, who negotiated with her the work-life conundrums many women face on their own. In that post, Sandberg vowed to her husband to continue to “be the parent he would have wanted.”

In the 1970s, Gloria Steinem famously declared that “women’s liberation will be men’s liberation, too.” The truth is more complicated. Ruth Bader Ginsburg came close with her line: “When fathers take equal responsibility for the care of their children, that’s when women will truly be liberated.”

Segregating men’s and women’s movements is counterproductive, says Marche. “You can’t get at the interesting problems—which are the way men and women live together and the actual negotiation between genders. That is the actual way we live our lives as men and women together.”

Update