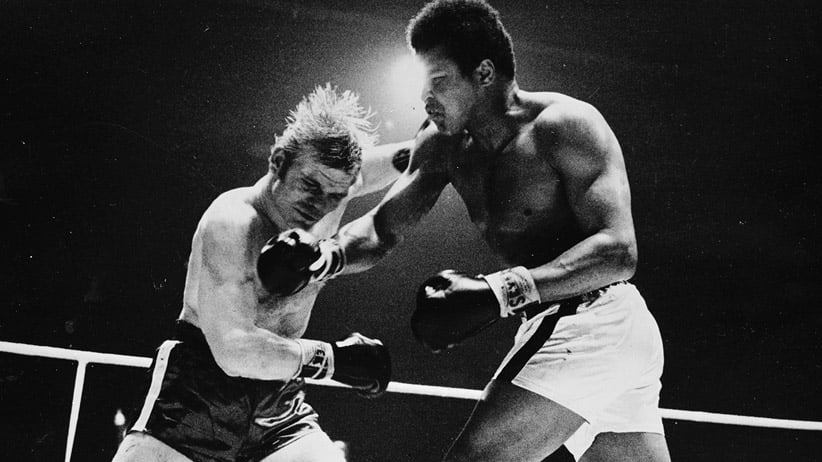

Muhammad Ali, the balletic boxer

Before Ali, heavyweights were clunky, ponderous lugs. He made boxing look pretty, dancing around the ring.

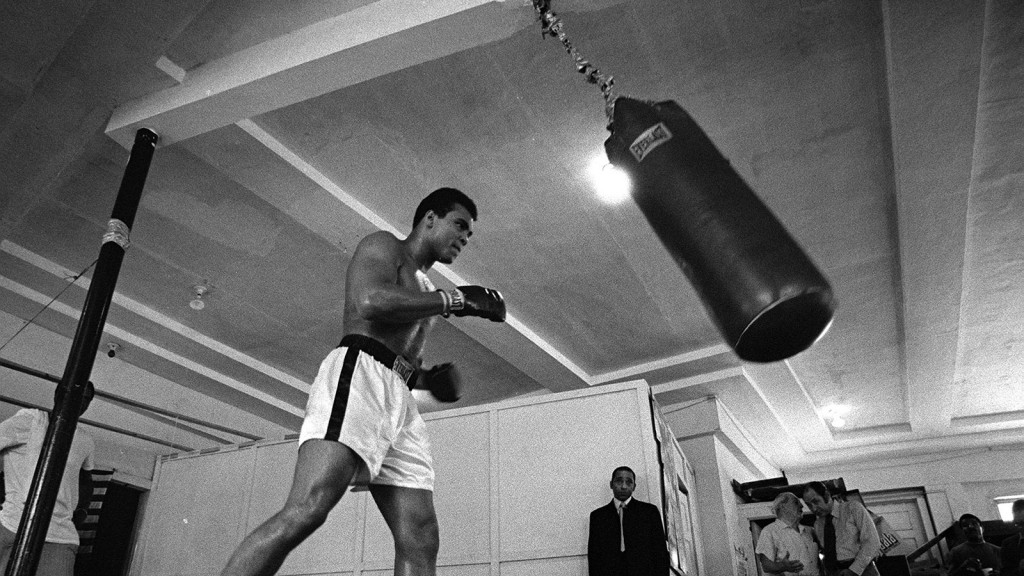

Sport, Boxing, Miami, USA, 6th March 1971, Former American heavyweight champion of the world Muhammad Ali pictured training for his fight with champion Joe Louis on March 8th. Popperfoto/Getty Images

Share

On paper, it was a tremendous mismatch. Gary Jawish, a 232-lb. veteran who had never been knocked down in his career, was slated to fight a 172-lb. high school student on a cold Monday night in March. It was for the 1960 Golden Gloves heavyweight championship. And it was going to be a bloodbath. More than 15,000 people showed up at New York’s Madison Square Garden to watch Jawish, a 25-year-old bear of a man with remarkable power, pummel this teenager. Some 18-year-old kid out of Louisville named Cassius Clay.

Little did they know at the time, Clay was in the process of reinventing heavyweight boxing. He was taking an indolent, thuggish division and breathing amazing life into it with astonishing quickness. All the matchups lied. No matter whom he faced, Clay was always younger, weighed less and didn’t punch as hard. He was a constant underdog. But all of that quickly faded away when he got in between those ropes and started dancing. All he needed were two feet flying in majestic, seamless motion to turn everyone into believers. “He just looked so pretty when he did his thing; when he was moving around the ring, doing the Ali shuffle,” says Sugar Ray Leonard. “I mean, everybody, not just me, most boxers tried to emulate that.” Before Muhammad Ali, heavyweight boxers were clunky, ponderous lugs who ambled around the ring in a half-crouch, throwing hands that carried the weight of mountains. They were powerful, sure. But they were like grizzly bears swatting away at one another until one dropped. They had no finesse. No air. No feet. Heavyweights simply hadn’t been taught to fight that way—that stuff was for the small guys. Boxing coaches of their day would emphasize getting low—planting the feet, bending the knees, slouching the head and raising the hands in order to form as strong a connection between earth and fist as possible. Then try to knock the other guy’s head off.

But from the beginning and through his prime, Ali was none of that. In most of his early fights his feet never seemed to touch the canvas. He was practically in flight as he boxed, darting in and out of danger. “His footwork was amazing,” said longtime Ali trainer Angelo Dundee in an interview with Sportsnet just before he died. “He was in and out so quick. But the press didn’t think this kid would make a fighter. He bounced around too much.”

What is both remarkable and indicative of that kid’s stubbornness is the fact that Ali’s style hardly changed between the first time he threw a jab as a 12-year-old and the day he won the heavyweight title 10 years later. When Cassius Clay started training at Joe Martin’s gym in Louisville, he boxed almost like a ballerina—always on his toes, leaving his hands near his hips and bouncing around the ring in endless circles. That was about as wrong as heavyweight form could be. Your legs were supposed to be stable, your hands held high. But Clay’s unorthodox style bred a new brand of boxer. “He was more of a hit-and-run guy,” says George Chuvalo, who fought Ali twice. “Hands down, moving around left and right, in and out. He used it extremely well.”

Clay immediately favoured the left jab, which Martin taught him to snap from different angles to keep his opponents off balance. The style was born more out of necessity than genius because Clay was inherently undersized. He was long but not thick and couldn’t afford to get low and slug it out with the big boys. “He didn’t want to get hit,” Chuvalo says. “I don’t blame him.”

Clay began dazzling opponents by dancing around the ring, avoiding the wild swats of his teenaged foes before darting in to score points with jabs and hooks. Even at that earliest point in his career, Clay seemingly saw the action develop two steps ahead of anyone else. He had an astonishing ability to anticipate his opponent’s attacks, always leaning just far enough away so the worst damage he felt was a graze. One day at Martin’s gym, a 17-year-old Clay sparred with Willie Pastrano, who was 24 years old and one of the top contenders for the world light heavyweight championship. “Willie couldn’t find this kid,” said Dundee, who was there. “Cassius was so quick. You think he looks quick when you see him in his later fights, but that’s slow compared to what he was as a young man. Slap, slap, slap and gone.”

The biggest stage for amateur boxing at the time was the United States Golden Gloves championships, a series of tournaments featuring the top non-professional talent in the country. Clay began entering the competitions as soon as he reached the qualifying age of 16, winning the national light heavyweight title as a 17-year-old in 1959. The next year, in order to avoid fighting his brother, Rudy, Clay made the step up to heavyweight. It was a noble gesture but also a dangerous one for Clay, who was still developing physically. He would need to find the courage to fight opponents who were older, bigger, stronger. He would have to guzzle litres of water before weigh-ins just to make weight. And he would have to rely on his feet more than ever.

But there was never an ounce of fear or hesitation from Clay, who made his presence known in classic form the moment he walked into the Chicago Golden Gloves weigh-in. He was there to fight Jimmy Jones, the defending national heavyweight champion. Jones was 22 years old and had at least two inches and 30 lb. on Clay, who was just two months past his 18th birthday. But if the younger man was intimidated, he never showed it. “Mr. Martin, are you in a hurry to get away from here tonight?” Clay asked his trainer within earshot of Jones at the weigh-in. “Not really,” Martin replied, perplexed. “Why?” Clay motioned at Jones. “This guy over here, I can get rid of him in one round if you’re in a hurry. Or if you’re in no hurry, if you want me to box, I can carry him for three rounds.” Martin shook his head and chuckled. “No, I’m in no hurry.” Good thing—his young fighter would need all three rounds.

Clay was on the move from the opening bell at a sold-out Chicago Stadium, circling counter-clockwise from the hulking Jones as he tried to avoid his bruising left jabs. “I did a lot of footwork. A lot of dancing. A lot of moving in and out,” he said at the time. Clay used his lone advantage to avoid most of the punishment, but by continuously dancing away from danger he rarely scored. Jones landed more shots and was earning a narrow victory after the first two rounds. But by the third, Jones’s legs grew heavy from the constant chase. That’s when the teenager started to score. Clay didn’t do much damage to Jones. But what impressed the judges in lieu of power was that dazzling footwork. Several times in the third round, Clay backed away from Jones, moving his feet forward and back as if balancing on a log. The shuffle seemed to momentarily mesmerize Jones before Clay lunged forward with a long jab. He repeated it twice as the third round came to a close, exposing Jones’s fatigue and helpless defence. If there is a classic Clay, this was it. Always moving, never stagnant. That third-round performance earned Clay the decision, and a date with Jawish in front of 15,000 people at Madison Square Garden.

Yes, Jawish had 60 lb. on Clay. Yes, he punched harder and was seven years older. No, he had never been knocked down before. But Jawish was also heavy, slow and flat-footed, which played right into Clay’s strengths. Jawish hung in for two rounds before spending much of the third with his hands up in front of his face, absorbing blows. Clay systematically circled left and right, throwing stiff hooks in between and around Jawish’s dozy defence. The crowd ate it up. At one point, Clay got so confident that he stood perfectly still, hunched slightly in that trademark lean as he sized up his foe. The instant Jawish took a step toward him, Clay threw a stiff left jab between Jawish’s hands and through his jaw. But with Clay it was never just one punch, and as Jawish’s face compacted, a right hook was already in motion over his left shoulder. The resulting blow to Jawish’s ear sent his chin to his chest, and by the time he pulled it back up, Clay had already circled away. The kid kept hammering away at his opponent’s temples until a long left sent the big man sprawling into the ropes, where the referee decided he had seen enough. Clay raised his hands in the air; he had conquered the odds, a feeling that would become very familiar. The crowd could only cheer—believers, all of them.

A national Golden Gloves heavyweight title. Not bad for an overmatched, undersized 18-year-old with form that made most boxing purists laugh. “He did the best he could with what he had,” Dundee said. “He licked a lot of guys with that. Muhammad was the greatest thing that ever happened to boxing.” There are no stats for this. Greatness is not something you quantify. It is something so boundless and transcendent that you cannot define it; you only know it when you see it. And when those feet got going, everyone saw it. Those feet revolutionized the heavyweight division. They changed boxing. Matchups can always lie. Hands and hearts, and even feet, cannot.