Newly discovered letters show darkness of WWI POW camp

Some 3,300 Canadians were taken prisoner during WWI. One Winnipeg soldier’s secret-code letters shed new light on their experiences.

(Photograph by Nick Iwanyshyn)

Share

Canada is gearing up to mark the 100th anniversary of its greatest military victory, the 1917 Battle of Vimy Ridge. As acclaim is once again showered on Lt.-Gen. Julian Byng and his Canadian Corps, a forgotten part of Canada’s wartime service is getting new attention: the fate of some 3,300 prisoners of war held in Germany.

The officers and men “deserve to be remembered because of their duty and devotion,” even though they don’t fit the victorious narrative of Vimy, says author Nathan Greenfield, who explores their experiences in his new book, The Reckoning. It interweaves Great War battles with grim POW life into a readable, engrossing, at times funny tale of determination, hope and bloody-minded stubbornness.

Though often away from the dangers of frontline trenches, their confinement came with its own privations. Isolated from news of the war, except that gleaned from new arrivals, prisoners existed on thin soups, were forced into gruelling work in dangerous places including iron works and salt mines, and could be ferociously punished—sometimes for no reason at all.

Many arrived in the camps after being wounded on the battlefield. Such was the case of Pte. Frank MacDonald, who had steel splinters removed from his eye after he was captured in 1916. Soon, hunger drove him to search through garbage pails in the Dülmen POW camp, where he discovered that the inedible meat in that day’s soup had come from a dachshund.

Germany, starved for workers, ignored international conventions regarding prisoners’ rights and ordered them to perform some of the most dangerous labour. By one estimate, upwards of 75 per cent of POWs in 1916 (some 1.2 million men, many Russians) were working.

When MacDonald and fellow prisoners refused to work in a coal mine after a friend died in a cave-in, they were made to stand at attention with bayonets at their back; MacDonald eventually collapsed onto a barbed-wire fence. On July 1, 1915, Canada’s 48th birthday, German guards punished Pte. Fred Ivey by tattooing an Iron Cross on his face.

“They had a mental universe that said, ‘This is like hell.’ This wasn’t a cliché, it was a living, breathing belief,” says Greenfield, whose previous book, the critically acclaimed The Damned, focused on Canadians during the Battle of Hong Kong in 1941 and their subsequent treatment by the Japanese in POW camps. MacDonald and his fellow POWs did what they could to hinder the German war effort, including posting a lookout in the mine keep an eye out for guards while the others rested instead of digging out coal.

Related: A century later, Beaumont-Hamel is Newfoundland’s raw wound

They also used every opportunity to escape. On Nov. 7, 1916, MacDonald and Lance Cpl. Wallace Nicholson broke through two sets of fences and escaped. After five cold nights evading patrols, they were close to the border with neutral Holland. Only in the morning did they realize their error: They’d crawled through the mud into Holland, then kept going, back into Germany again, where they were captured.

“They were fearless in ways that only men who are young and who have survived battles are,” explains the author. Roughly 10 per cent of Canadians broke out of camps, some multiple times, with about 200 making it to safety. The British believed the Canadians escaped more often because they were used to being outside. Greenfield agrees the rural nature of Canada at the time helped: “Their field craft skills, beside what they learned as soldiers, came naturally to many of them.”

What sustained the prisoners were letters and parcels from home. So crucial were those food parcels to their survival that they hid desperate messages in their letters. Greenfield recounts how one soldier asked after “my old school chum, W.E.R. Starving.” (In 1917, those homemade packages were replaced by standard Red Cross issue.)

FROM THE ARCHIVES: The experiences of a Canadian prisoner of war, from 1917

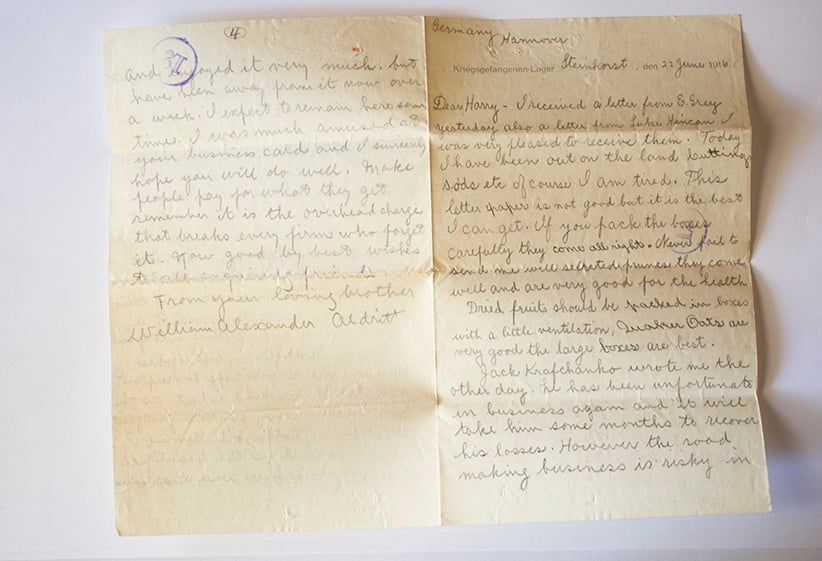

On June 22, 1916, Sgt. W.A. Alldritt wrote a seemingly innocuous letter to his brother Harry in Winnipeg. First there was his news—he was tired from cutting sod on a farm—then his food requests: dried fruits packed in ventilated containers; he also wanted large boxes of Quaker Oats.

Related: The Battle of Jutland was chaotic, bloody and a mass of ironies

While most of his writing slanted forward, some tilted to the left. Those backhanded words, when pieced together, asked for special additions to the package: road maps of Hanover and Westphalia. The cipher was recently discovered by W.A.’s grandson, Robert. He doesn’t know if Harry sent off the maps, but points out that Alldritt staged four unsuccessful escapes during his time as a prisoner and appears to have helped other prisoners with their own plans.

Until a few years ago, Robert Alldritt knew only shards of his grandfather’s experiences during the Great War. His own father was a toddler when W.A. Alldritt died in 1933. In 2011, Robert inherited four plastic totes stuffed with letters, photographs, newspaper clippings and scrapbooks. “It was jumbled, disorganized and quite overwhelming,” Robert says. It was also extraordinary.

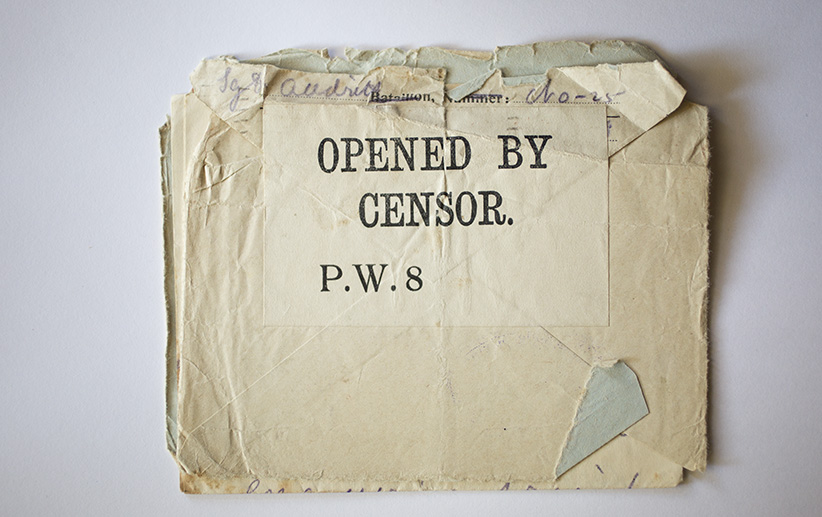

Those totes contained some 400 letters, many in their original envelopes, stamped with censor’s markings and postmarked from the eight camps he stayed in after his capture in 1915. “The letters were calling to me,” Robert’s wife, Danielle Giroux, says. She arranged them in chronological order and they began reading. Soon, they realized the uniqueness of the collection. According to Greenfield, it’s perhaps the most complete in existence. Indeed, the Alldritts are in the process of transferring the letters to the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa.

Meanwhile, they keep teasing new information from the collection, helped by W.A. Alldritt’s wartime diary, found by a German soldier on the battlefield after his capture. It eventually ended up at Library and Archives Canada in Ottawa.

In one of the postcards made from a picture taken inside the Steinhorst work camp near Hamburg, Alldritt wears a rough cardigan. His grandson thinks it’s the large blue sweater that he mentions knitting in one letter. Some of the other letters referred to a friend, Jack Krafchenko, a name unknown to the family. The answer popped up when Robert typed the name into Google: Krafchenko had staged a daring escape from a Winnipeg police station in 1914; W.A. Alldritt used the then-recognizable name to slip word of his own prison breaks past unsuspecting German censors.

While Alldritt, MacDonald and others endured harsh treatment; the fate of the prisoners often depended on the commandants of the camps. “Some treated them as well as they could,” Greenfield notes, in an era where food and supplies were increasingly scarce.

Sometimes, it was the inmates who helped the Germans. In 1917, food was so meagre that Canadians working on German farms gave chocolate from their parcels to hungry children. While prisoners fared better on the Allied side, Greenfield notes both sides violated treaties by making prisoners work in trenches in the direct line of fire. In June 1917, the British and Germans agreed to keep POWs more than 30 km from the front.

Many found their wartime suffering made life after 1918 difficult. Before he enlisted, W.A. Alldritt was a big strapping athlete. After being gassed and captured at Ypres in 1915 covering his company’s retreat with machine-gun fire, he worked in salt and iron mines. He contracted Spanish flu before returning to Canada in 1919; by then, Alldritt was almost unrecognizable.

Like many POWs, his claim for financial reparations for continuing disabilities was rejected by the Canadian government. In 1938, his widow, Agnes, was awarded a war widow’s pension. She’d successfully pleaded her case by submitting clippings and letters from that remarkable collection.