Oy vey, that’s not funny: What happened to Jewish comedy?

Modern comedy was shaped by Jews. That’s ancient history now.

Share

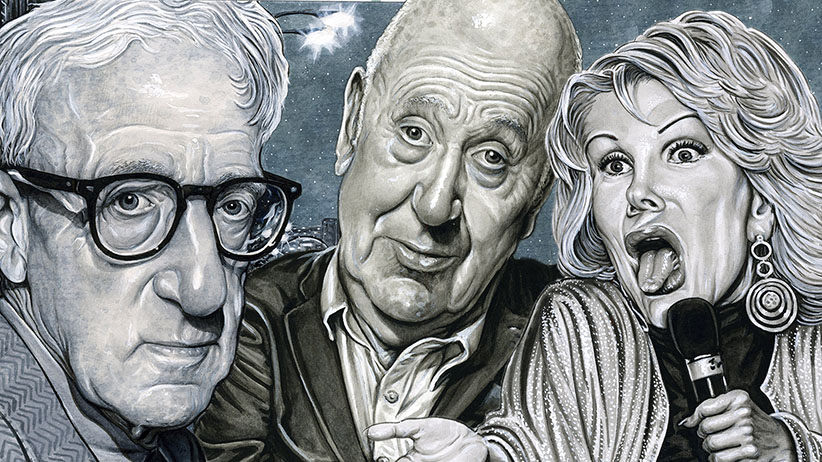

When sitcom king Norman Lear released his autobiography in the fall, he was upfront about the biggest influence on the classic shows he created, such as All in the Family and The Jeffersons: “At age nine I learned that people disliked me because of my Jewishness,” he told the Jewish Daily Forward. “It was a profound discovery and influenced everything I ever felt about the human species, the human condition,” not to mention the characters he helped create, like Archie Bunker or Maude. The title of Lear’s book itself, Even This I Get to Experience, uses an inverted word order derived from Yiddish. But Lear is 92 now, and as he promotes his book, he’s reinforcing a surprising new feeling a lot of people seem to have: Jewish humour, once dominant in North American comedy, is starting to fade as an influence in the modern world of entertainment.

Not that there are no Jewish comedians or comedy writers. But many of the most successful ones are over 50, like Judd Apatow, Jerry Seinfeld, Larry David, or Big Bang Theory creator Chuck Lorre. The biggest star comedians are just as likely to be lapsed Catholics, like Louis C.K., or practising Catholics, like Stephen Colbert. Compared to an earlier generation, “there are fewer Jews as the dominant comedians, in terms of the Jack Bennys, the Eddie Cantors, the Sid Caesars, the Woody Allens,” says Joseph Dorinson, a history professor at Long Island University and an authority on Jewish humour.

The Jewish strain in comedy is increasingly viewed as belonging to a lost era. When Joan Rivers died, she was celebrated as an old master who defined what we thought of as a Jewish comedian: a New Yorker with an unmistakable accent and inflections, whose broad insult humour “attacked the beautiful people, who were mostly non-Jewish, or Jewish converts like Elizabeth Taylor,” says Dorinson. Alan Zweig, a Canadian documentary filmmaker, made a film called When Jews Were Funny, which premiered last year at the Toronto Film Festival, where he argues that Jewish humour is a dying art in general. Zweig says he has told audiences that while today’s best Jewish comics may be as funny as the old ones, “in my experience, the average Jew in the deli might be less funny than their grandparents. I didn’t get a lot of disagreement.”

It might seem a strange thing to mourn, but then, the prevalence of Jewish comedians and comedy writers was more than just a statistic; it was a point of cultural pride for many North American Jews. “Growing up, I too was proud of the domination of Jews in comedy,” Zweig says. “Though I was also confused. I had been brought up to believe ‘they all hate us and they won’t let us succeed,’ so how had we managed to get around their prejudice so thoroughly in this one field? But that probably made me more proud.”

It’s particularly significant that these comics were able to appeal to a mainstream audience without ever hiding their Jewish identity or influences. Writer-director-comedian Mel Brooks, who is being honoured starting this November with a program of his films at Toronto’s TIFF Bell Lightbox, saw most of his movies become big hits while being full of lines like “May the Schwartz be with you” (Spaceballs) and with Brooks himself playing parts like a Yiddish-speaking Indian chief (Blazing Saddles). “He made movies in a variety of genres, like Young Frankenstein or a Western, but the Jewish references, sometimes Yiddish, are always present in all of these different milieus,” says Jesse Wente, who is programming the Brooks retrospective. “Even a non-Jewish character can have Jewish traits in a Mel Brooks movie.” That was part of the style that Rivers, Brooks, Don Rickles and others worked in—comedy for a mostly Gentile audience, but suffused with Jewish content.

Where did this style come from, and why does it seem so lost? According to another documentary, When Comedy Went to School, it was partly shaped by resort hotels in the Catskill mountains, which catered to a predominantly Jewish clientele in the mid-20th century. Many comics got their start performing at these resorts. “Danny Kaye, Jerry Lewis, Jackie Mason, they all had one kind of connective tissue, which was this Catskill hotel experience,” says Larry Richards, writer-producer of the film, which will be released in Canada on January 27, 2015. Those places are gone now, and with them, a lot of the training in that brand of humour.

The Catskill era also coincided with an awakening of Jewish identity. After the war years and the early 1950s, when Jewishness tended to be more muted, writers like Mordecai Richler and Philip Roth, or comedians like Woody Allen and Brooks, began to express the point of view of the North American Jew who is assimilated but doesn’t quite feel assimilated. Wente describes these artists, including Brooks, as “aware that there is this division, that there are stereotypes that can play to both sides.” This type of humour continued to be common well into the 1990s, when Adam Sandler popularized The Hanukkah Song on Saturday Night Live, and the world’s most popular television show was originally dismissed by NBC as being too Jewish: “The Seinfeld phenomenon was definitely Jewish humour reheated and updated,” says Dorinson. “Even George, who has an Italian surname, is Jewish.”

For some, the decreased visibility of Jewish humour can be traced to the lack of the alienation, the sense of being at home and not at home in North America, that gave this kind of humour a lot of its distinctive flavour. “I think a lot of people agree with me that success and contentment have not had a positive affect on the humour of the people,” Zweig says. It may also be that Jewish comics had so much influence that their self-deprecating style has been co-opted by the industry. “Most modern standup comedy still strikes me as ‘Jewish’ even if it’s not as easy as it once was to pinpoint the influences,” Zweig continues. “But there’s been so much cross-pollination that [it’s] not as recognizably Jewish as it once was.”

It may be that what has vanished is not so much Jewish humour, but what many people grew up thinking of as Jewish material. Veteran comic Paul Reiser told a Forward interviewer that the decline of Jewish comedians is a myth: there are plenty of them, he said, “but they’re just not playing to the same sensibilities you recall. They’re not talking about the immigrant experience.”

A comic like Sarah Silverman embodies a different kind of Jewish experience, making jokes about the fact that many North American Jews are conscious of having white privilege, even as they’re conscious of being a minority group. “People are always introducing me as ‘Sarah Silverman, Jewish comedienne,’ ” she said in her act. “I wish people would see me for who I really am — I’m white!” The increased prevalence of Jewish-Christian intermarriage is also a subject for comedy: Both Amy Schumer and Lena Dunham make jokes about being the product of mixed marriages, and Seth Rogen incorporated it into his film Neighbors, where his wife (Rose Byrne) snaps at him: “What is it with you f–king Jews and your mothers?” These jokes may play to modern Jewish life just as traditional Jewish humour did.

Dorinson notes that the older kind of Jewish humour, too, “constantly resurfaces, in times of crisis particularly”—the kind of crisis that could be brewing thanks to increased tension in Europe and elsewhere. Raymond Simonson, head of the British-Jewish culture centre JW3, told the Independent earlier this year that comics are occasionally “being booed when they talk about their Jewish heritage,” and Chelsea Handler, the only major female host in late night, told the Huffington Post that her people “are underdogs—not in my world,” the world of entertainment, she noted, “but there’s still a lot of anti-Semitism going on.”

Of course, most Jews would rather be unfunny but happy than be funny underdogs. But in a world where Jews are increasingly split on issues like Israel and religion, Dorinson says humour could be “a stabilizing force in the Jewish community, more significant than religious rituals.”

That might help explain the increased sense of longing to preserve Jewish humour, which is almost like preserving Judaism itself. JW3, which opened last year in London, is devoted to secular Jewish culture, including a comedy festival: “I hope people who might never think of going to a synagogue will come here,” Simonson said. And Zweig talks about making When Jews Were Funny almost as if it were a religious reawakening: “It was this huge reminder of how much I love Jewish humour, which I hadn’t been all that exposed to in recent years.” As observance declines, reverence for Jewish comedy and its dying traditions may continue to increase. “When I hear my kids quote Mel Brooks records,” Reiser told the Forward, “it’s as warm to me as if they quote the Torah.”