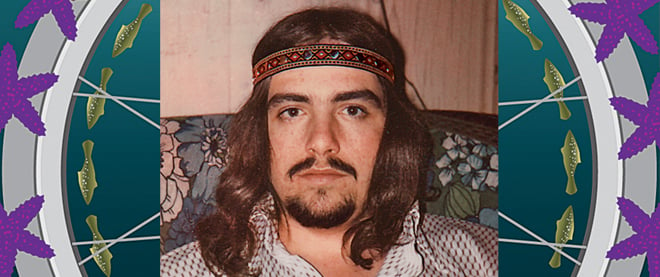

Peter Devoe

After a horrific car accident, he found a new lease on life in his wheelchair. But it was diving that really made him feel free.

Illustration by Marian Bantjes

Share

Peter Devoe was born on July 28, 1955, in Prince Albert, Sask., the oldest boy of six children. He had a Catholic upbringing, singing in the church choir, and he loved the outdoors, fishing and hunting with friends in his spare time. When Peter reached high school in the early ’70s, like most young men of the day, he grew a moustache and long hair that he would keep for good. At their school’s welding workshop, Peter and his friend, Grayden Tyskerud, learned to fix just about anything, a skill that would come in handy later.

In the summer of 1978, Peter was living in Cranbrook, B.C., working at a sawmill, when a car crash radically changed his life. Travelling with friends on the road leading from Yahk toward Cranbrook, their car hit a rock wall and crumpled. Peter suffered a spinal cord injury, lost two fingers and one of his friends. After the crash, Peter’s mother gave him a medallion of St. Christopher, the patron saint of travellers, which he wore around his neck.

Being in a wheelchair did not make Peter feel sorry for himself. To the contrary, he never moped, and wouldn’t let others do it either. In the lobby of GF Strong, B.C.’s largest rehab centre, Peter would meet other patients and say, “Okay, everybody, let’s get into a taxi and go for a ride.” They would get an ice cream or a couple of drinks—ordinary things that nevertheless may have seemed undoable to some. “When you have an injury like most of us had, to have somebody take the lead and get you back out doing something was major,” says fellow patient Robin Devoe. Peter was to blame for introducing Robin to his brother Joe, who ended up moving to B.C. because of her. They have been happily married ever since.

Peter eventually checked himself out of GF Strong. His long-standing motivation to fix things led him to build his own exercise equipment in his apartment. It wasn’t long until he could actually walk with the help of a cane, but he preferred the wheelchair, which was faster and less cumbersome. Grayden remembers his daughter and her uncle Pete zipping down a hill next to their place in Nanaimo, the two on Peter’s wheelchair, his long hair flying in the wind, the little girl with a huge smile on her face. “That was magic, just magic,” Grayden recalls.

Racing marathons, playing basketball and volleyball, Peter had found a new lease on life in his wheelchair. He took computer programming at what was then called Capilano College, and joined the Vancouver Cable Cars, a pioneering wheelchair basketball team on which Terry Fox had once played. A friend recalls Peter pointing to a skinny boy in a Cable Cars uniform before a game and saying, “This kid’s gonna go around the world on a wheelchair!” It was Rick Hansen, who was then preparing for his Man in Motion World Tour.

Peter developed a special skill to encourage people to get involved in sports, especially disabled youth. For Kathy Newman, the director of the B.C. Wheelchair Sports Association—where an award in Peter’s name was established for young athletes—he was “a role model for other wheelchair athlete participants.” Wendy Alden, an able-bodied volunteer at the organization, recalls that once, when she was soaked and struggling to finish a race under heavy rain in Vancouver’s Stanley Park, Peter, who had already crossed the finish line, wheeled his way back just to tell her, “You can finish this, come on. Run.”

In the early ’80s, Peter and his friend, Lenny Marriott, who has a polio-related disability, learned to scuba dive. Lenny, now a diving instructor himself, says that being underwater made them feel like astronauts stepping out of a spaceship. Peter fell in love with it: the freedom, the weightlessness. He became a deft diver, and would do it as much as possible, often with his brother Joe, while Robin and Peter’s fiancée, Linda, stayed out of the water as an onshore crew.

On March 13, 1985, Peter and Joe went hunting for crabs off Cates Park, in North Vancouver, where their family had gathered for a picnic. It seemed like just another dive, but Peter never resurfaced. He was 29. More than 26 years later, on Oct. 23, 2011, not far from where he had been diving, two fishermen pulling nets out of the water found a human body in scuba diving gear entangled in the mesh. Peter still had the St. Christopher medallion his mother had given him.