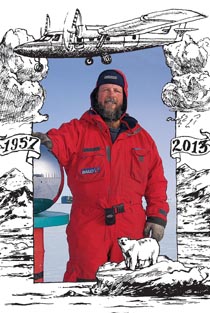

Robert Murray Heath

He’d spent his life flying around the world—he even married his wife on a flight

illustration by team macho

Share

Robert Murray Heath was born Nov. 7, 1957, in Mississauga, Ont. His father, Robert, was an engineer and his mother, Betty, was a telephone sales operator. Robert Sr. owned a hobby plane and Robert spent as much time as he could beside his dad in the cockpit, falling in love with planes.

Robbie to his parents and one older sister, Gail, “Bob” to most everyone else, he attended Mississauga’s Allan A. Martin Public School. When he was 12, he joined the Air Cadets, where he learned to fly gliders, then small planes, and earned his pilot’s licence. After graduating from Gordon Graydon Memorial Secondary School, he moved to Moncton, N.B., to do commercial and instructor flight training.

In 1985, Bob took a job with Sabourin Airways in the small community of Red Lake, in northwestern Ontario. He flew small planes—the Beechcraft 99 and Piper Navajo Chieftain—mostly to remote reservations and on hunting and fishing trips. On a medevac flight, he met Lucy Geno, a dark-haired nurse who worked at the Red Lake hospital. She was 10 years his elder, and he courted her with gifts of doughnuts and rabbit-trimmed hats. Lucy was the mother of three grown children when the couple met, and Bob soon became Papa to them all. The couple married on Nov. 17, 1990, in a Twin Otter flying at 5,280 feet—exactly one mile—above Red Lake. Lucy wore an embroidered red parka; Bob wore his flight suit.

Bob, who had a beard, sparkly eyes and a full belly laugh, was “mum’s soulmate,” says Helen Prest, Lucy’s daughter. With his quirky sense of humour, he was “always up to some sort of shenanigan,” says pilot Norm Wright.

In 1991, Bob found work in Inuvik, N.W.T., just north of the Arctic Circle. He piloted Twin Otter planes for Kenn Borek Air Ltd., serving remote Inuit communities and delivering what he called “mad scientists” to ice floes on polar-bear research expeditions. Lucy followed two years later. They settled into a burgundy townhouse, which quickly filled up with Bob’s books and collections of Aboriginal paintings and Inuit carvings. Bob soon became a legend in the Arctic flying community.

For the past 15 years, he’d leave the Arctic in the fall and fly a Twin Otter all the way to Antarctica, the bottom of the Earth, a four-day trip; he spent the Canadian winters there, delivering scientists to research stations and snapping photographs of the striking, barren landscape in his spare time. A man of insatiable curiosity, he never failed to ask what they were doing, why and how he could help, and collected patches from various countries’ research outposts to stitch to his leather aviator jacket. In the spring, he’d fly back to the Arctic, stopping off to see family in Winnipeg or Toronto, regaling them with tales of his latest exploits at the frozen ends of the Earth. (He was a talented, if long-winded, storyteller). When he wasn’t at either pole, Bob zig-zagged over the globe, ferrying planes to Asia or South America for Kenn Borek.

To Bob, “flying was an adventure,” says his son-in-law Joe Prest. “Flying in the Arctic on Monday,” Bob once wrote on a pilot message board. “Golfing in Scotland on Wednesday, and seeing the Pyramids two days later.” It was quite the life. Once, a woman gave birth in the back of a Navajo plane he was piloting. Bob loved teaching younger pilots and had a talent for foreign tongues. Fluent in Spanish and Italian, he spoke passable Ojibwa and Tagalog, a language spoken in the Philippines.

Still, every adventure took him home to Inuvik to Lucy, and Bob’s little bichon frisé, Sebastian, who waited atop his big leather chair. On the ground, Bob spent his days with his nose deep in a book or whipping up elaborate meals for his large family, which included six grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren. He loved to eat and cook, especially shrimp, but Helen says he’d leave the kitchen “a right wreck.”

Last October, Bob took off for another season in Antarctica. On Jan. 23, he was flying a Twin Otter with two other crew members over the remote, jagged Queen Alexandra mountain range, en route to an Italian research station at Terra Nova Bay. They never made it. Two days later, rescue crews spotted the plane’s tail jutting from a steep, 3,900-m slope, embedded in snow and ice. They deemed the crash “not survivable.” Bob was 55.