Dr. Sara Seager on unlocking the universe’s mysteries

A renowned Canadian exoplanet expert talks NASA’s big announcement and the allure of finding another Earth

Sara Seager. (John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation)

Share

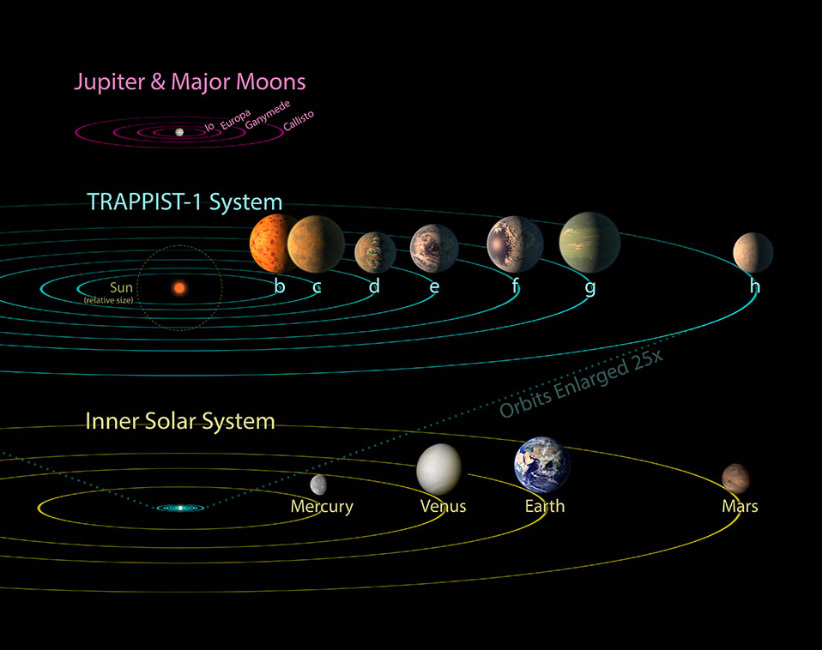

Finding a nearby Earth-sized planet with the right conditions to have water would be enough to get most astronomers excited. But to find seven Earth-sized planets a mere 39 light years away—all of them orbiting a dwarf star name Trappist-1? The news unveiled at a Wednesday news conference was enough for even Google to pay homage to the major discovery with their home page Doodle the following morning. But what does this mean for all the amateur astronomers out there—or perhaps those simply curious why this was such a big announcement?

To get a better understanding of the discovery, Maclean’s spoke with Sara Seager, the Canadian-born astrophysicist and planetary scientist at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (who was awarded a MacArthur Genius grant for her work on exoplanets) who was on hand as an independent expert at the NASA announcement on Wednesday.

Q: Why is this such a big deal?

A: People are making a big deal about it because it’s the first time we’ve had a bunch of planets we could actually study further for signs of water and life. We have thousands of exoplanets already, but the ones that we really care about are the ones that have potential.

Q: Every time I read about a newly discovered planet outside our solar system—an exoplanet—there’s always this excitement about them having water.

A: We definitely have a concern that it’s confusing the number of times astronomers make announcements about this stuff. Until now, including these planets, we only speculate that they might have liquid water. The difference here is that there are seven small planets. And unlike any planet we’ve talked about before, these ones can actually be studied further to see—without speculation—whether there’s water vapour.

Q: So not only can they be studied closer, seven planets mean the odds are seven times better at a breakthrough?

A: Exactly.

Q: These seven exoplanets are, what, 39 light years away?

A: That’s right.

Q: So what good is that for us?

A: It’s pretty far. We can’t travel there. But in astronomy, compared to everything in the universe that we’ve studied, that’s right next door. The reason it means something to us is that it’s close enough for us to study in detail. There are lots of other planets that have been found, but they’re just too distant. In this case, closer means brighter. The fact that it’s close and bright means we can look at it in more detail.

Q: What’s the best-case scenario? Life on one of the planets?

A: I think so. The best-case scenario is if we can find signs of life and be fairly confident in attributing it to life.

Q: And the worst-case scenario?

A: The worst case is somehow these planets have no atmospheres at all. Winds and radiation from the star has literally eroded the atmosphere so that they’re lifeless. Rocky worlds. That’s the worst-case scenario—but it’s still not terrible. Understanding different planets in their environments is still really important. So if these planets are dead lifeless worlds, it will still be useful for us.

Q: Why not talk up the possibility of aliens with these kinds of discoveries?

A: The reason why we’re hesitant to talk about aliens is because it’s an even longer shot. We believe hydrogen and oxygen are pretty common and they’re going to pool together to form water. It’s inevitable that some planet will have the right conditions. But the right conditions for life is even more speculative.

Think of it like an emergency room. We have a triage process. The first step is to find the planets and identify the ones we think might have the right temperature for liquid water. The next step is look and see if there’s water vapour. After that, we’re going to look for gases. We’re trying to manage expectations.

Q: So for these seven planets, the next step is finding water vapour?

A: Yes. That’s why you often hear about water.

MORE: Scott Feschuk on what we learned from the NASA announcement

Q: You’ve defined your research goal on your website as “to find and identify another Earth.” I know you weren’t part of this particular research team, but is this a big deal for you on a personal level?

A: I don’t know if we can call these ones “the other Earth” because they orbit a star so different from our sun. The star is so cold and so dim. It it was any smaller and colder, it wouldn’t be a star. It wouldn’t be able to have fusion in its core.

But yes, it is exciting because it’s a lifelong goal and the thought that we can study a planet to see if there’s anywhere remotely like Earth in the next few years is a really big deal. It’s accelerating my hopes.

Q: Do you ever get the feeling of, ‘Dammit, this better be it’?

A: No. (laughs) We don’t know what nature has in store and nothing is guaranteed here. At some level, we might have to really wait for the true earth twin, the earth orbiting the stars like our sun.

Astronomy is one thing because it’s so hard to find these planets, but every time we have new technology, it opens up a new set of planets we can study. The team that found this [discovery], they purposely went looking for the easiest type of stars to find planets around. The harder ones comes later and, arguably, the sun-like star is one of the hardest.

Every time there’s a discovery in space, it seems to hit the front page of the newspaper. Why are space discoveries so special?

A: I think at some level we all have a fascination with the mysteries of the world around us and the universe out there. And, sometimes, I think people just want a distraction. It’s something you can get excited about that doesn’t have to do with politics. It makes you think there’s something larger than ourselves—and that can be very powerful.

Q: Is there worry about these major discoveries happening so often that people will become disillusioned because the best-case scenarios don’t pan out?

A: I used to worry about disillusionment and I used to get worried about the steady amount of press, but most of the enthusiasts—the ones who read and tweet about it—don’t mind. I hear people say, “I know and I don’t care. Keep this stuff coming.” That’s surprising to me.

Q: I’m looking at a newspaper front page right now with all seven planets in a perfect line—and they’re all so perfect looking, colourful and beautiful. But they couldn’t even see some of these planets, I understand.

A: That’s right.

Q: But the artist renderings that make the planets look so cool when, well, who knows what they actually like?

A: Yeah. I agree with you. I think they wanted something you can look at because we don’t have pictures and showing you a transit light curve—the real data we look at—is really meaningless in terms of speculating what the planet might look like.

When finding Jupiter-sized planets used to be the frontier, they all looked like Jupiter—which is silly, right?

Q: What does this discovery mean for children?

A: You know how children are quite self-centred, it turns out? I don’t think it has a huge meaning for them now, but what it means is the world they’re growing up in is very different from children of previous generations. We had Star Trek, Star Wars and Futurama—and we still do—but for children today, they will grow up in a world where other stars were known.

Q: So Futurama won’t be as outlandish for today’s kids as it might have been for us when it debuted almost 20 years ago?

A: It might seem outlandish because we don’t have a way to travel to these other stars—or cryogenically freeze ourselves for 1,000 years—but the fact that planets are out there will no longer be a made-up thing.