How geologists found the world’s oldest fossils in Canada

The geologist who dated what appear to be the world’s oldest fossils on what it took to make the discovery in Quebec

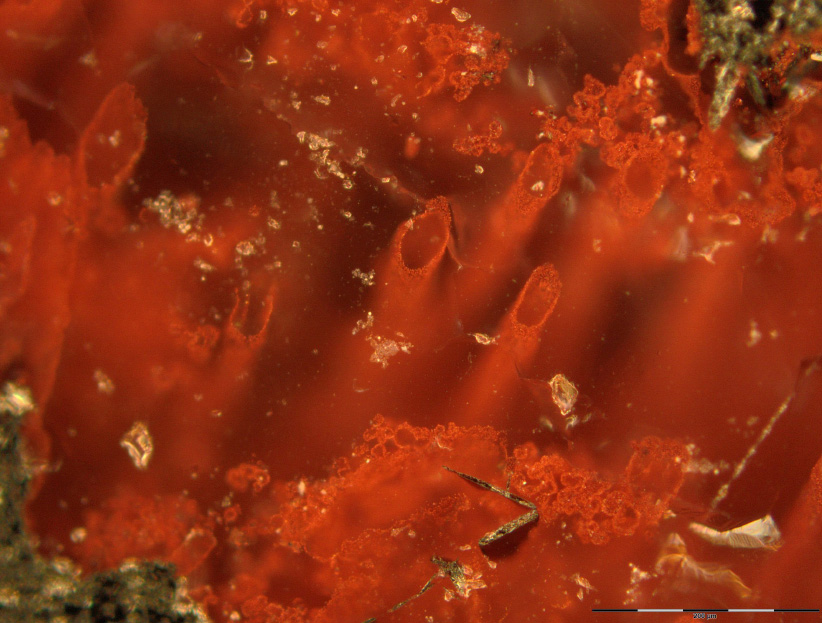

This microscope image made available by Matthew Dodd in February 2017 shows tiny tubes in rock found in Quebec, Canada. The structures appear to be the oldest known fossils, giving new support to some ideas about how life began, a new study says. (Matthew Dodd/AP)

Share

The oldest proof we have of life on Earth is in Quebec, according to a team of international researchers. On the edge of the Hudson Bay, geologists and biologists from England, Australia, the United States and Canada collected fossils of microscopic lifeforms. On March 1, 2017, they published an article in the journal Nature, suggesting that these lifeforms existed 3.7 to 4.3 billion years ago, before the planet had oxygen or oceans—meaning life could begin in other barren parts of the universe, too. For a look behind the scenes of the discovery, Maclean’s spoke with Jonathan O’Neil, a geologist at the University of Ottawa who dated the fossils.

Q: Can you describe the moment of discovery?

A: I was with some of my colleagues at the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington. The first moment, you don’t even believe it. You say, “that can’t be.” So you reanalyze it, and you get the same result. You redo it again, redo it again, redo it again, and you start coming back with the same data, same results, same numbers, and you start to believe it. It’s a weird feeling. It pushes everything back.

Q. Why is the finding controversial?

A: Rocks are always dated with radioactivity. We use that as a timer. The golden standard for us is we’re trying to date a certain mineral, a Zircon. We’re excellent at it. We can get super nice and precise and robust dates. The only drawback is you need Zircons to do it. These rocks from northern Quebec, they don’t have them. We used a different clock. It’s only good for rocks that are 4 billion years old. We’ve done it for some rocks from the moon, but it’s the first time we’ve done it on Earth.

Q: What was the hardest part of this unprecedented research?

A: The weather. First you need good weather to get there. If it’s cloudy or foggy, the planes are not going. You take a flight from Montreal to [the village of] Inukjuak. You find someone who has a boat and go 35 or 45 km south. It takes an hour and a half. In the field, when it’s rainy, it’s difficult—not because we don’t want to get wet, but the lichen gets slippery, and it can be dangerous. We’re itching to put our hiking boots on and go out and do fieldwork, but we’re stuck in our camp for three or four days.

Q. Can you describe the camp?

A: There’s nothing. It’s the middle of the tundra. When we first went, no [scientists] had been there. We had to scratch our heads—what is this rock, what is that? You have to fly all your stuff, all your gear, all your food there. You set up your kitchen stove and your tents, and you’re good to go.

Q: Is the site now blocked off to protect the rocks from animals?

A: No, it’s their kingdom. It’s where they’re living. Frankly, I don’t think animals could do much to them. I mean, they’re still rocks.

Q: What about humans?

A: Technically, anybody could go. It’s the Inuit’s backyard, so you can’t just show up there, but you [can] get in touch with the right people. You’re not supposed to go collect samples without asking their permission. They were pretty happy and very, very helpful. If you’re going for the right reasons, they’re pretty happy to see you there.

Q: Over time, will the debate about your findings be resolved?

A: First, people will doubt it. Some people will come up with other explanations. I’ve seen it many times. If you ask me, I’ll say [the rock is] 4.3 billion years old. If you ask someone else, they’ll say, ‘no, this old guy is full of crap.’ But then once we pass over this … if it stands this scientific scrutiny, that’s when you know it’s solid.