Meet Dr. Steven Zeitels, the man who saved Adele’s voice

Dr. Steven Zeitels explains the rise in vocal surgeries, like the one he performed on Adele, and how they’re helping in the fight against cancer

British singer Adele performs the song “Skyfall” from the film “Skyfall,” nominated as best original song, at the 85th Academy Awards in Hollywood, California February 24, 2013. (Mario Anzuoni/Reuters)

Share

When Adele won a Grammy in 2012 for best pop vocal performance—the first of six at an award show she took by storm, for the heartbreaking album 21—it seemed likely that she would thank her friends, her family, her colleagues. And while she did begin with a tribute to her co-songwriter, the next names up were, curiously, a crew of medical professionals. “Seeing as it’s a vocal performance, I need to thank my doctors, I suppose, who brought my voice back,” Adele said.

The first name on that list: Dr. Steven Zeitels, a Harvard professor and the director of the Massachusetts General Hospital Voice Center. When Adele visited his Boston office at the end of 2011, 21 was quickly accelerating into an unstoppable record-smashing force—but she was rendered silent, with a benign polyp in her throat causing recurrent bleeding. Zeitels admits he wasn’t familiar with her music before performing vocal cord microsurgery—but as she releases the hotly anticipated 25, he now knows it’s an incredible voice that’s hard to ignore.

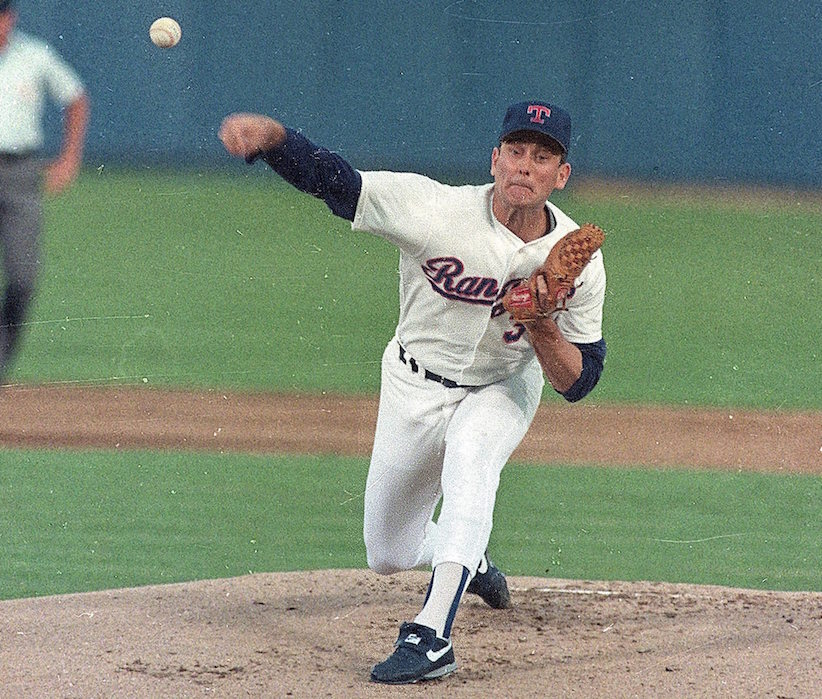

Adele’s isn’t the only one to go under Zeitels’ knife. He’s performed surgery on singers like Julie Andrews, Sam Smith, Steven Tyler, Cher, Lionel Richie, Roger Daltrey and more; he’s worked on sports commentators too, from Joe Buck to Dick Vitale. Maclean’s spoke to Zeitels about how helping singers is improving outlook for cancer patients, what it has to do with baseball, and the evolving perception of his surgical practice.

Q: What got you interested in this particular field of medicine?

I was inclined to do a surgical discipline rather than a medical one, and I actually had an older brother who was a few years ahead of me. His advice to me when I was a student was to research the best departments in the school you’re in. I was in Boston University doing the six-year med program, and over and over again, I was hearing otolaryngology. And the reason for that is that laser surgery as an approach to remove things out of human beings was actually created by my teachers, and it was the first time a laser was used to remove soft tissue from humans and it started in the larynx. I simply migrated to that chairman whose name is Dr. Stuart Strong who is about 92 today, and I walked into his office as a 22-year-old, and he said, ‘Well, let’s plan your life.’

So I became an ENT surgeon, and then started exclusively doing throat cancer and head/neck cancer. Then when I was in my 30s, the people I was seeing at shows started coming to my office for help with their voice, and I said, ‘Well, I could do this too.’ And in fact the field hadn’t matured fully—even though it had been around for 100 years, it was kind of stagnant, and I realized there was a lot that could be done to enhance the management of singers. I kept both those pathways going, even today—I spend a substantial amount of time treating cancer patients, and a substantial amount of my time taking care of performers and vocalists. If I was an orthopaedic surgeon, it would be the equivalent of doing the worst sarcomas, and also managing Olympic athletes.

Q: That’s a unique combination.

It requires an incredibly high level of precision. And what I’ve tried to do in the last 25 years or so is enhance both surgeries. I tried to bring ontologic thought processes into the management of singers, because there was kind of medicine that was more…it wasn’t precise, there wasn’t a lot of research. There were too many shots and too many potions. So I wanted to bring more scientific order to that. And I learned so much about human voice from watching the singers and their vocal cords vibrate that I was able to get much better cancer results.

Related: Say ‘Hello’ to Adele, 2015’s anti-pop-star pop star

Q: Has working with celebrities raised awareness inside and outside the scientific community for this kind of research?

I think you have it completely right. What’s been wonderful is the willingness of people have depended on their voice for their lives and livelihoods to participate. One thing we’re so proud of, and it’s still evolving, is the Voice Health Institute, where two patients brought themselves together and created a federal nonprofit. From that, the honorary chairwoman is Julie Andrews, and this was just after the period where I did several procedures to try to enhance her voice—I just couldn’t bring back her full voice because of what happened in the first procedure. And we’re still doing key research to try to solve that problem. It’s not going to happen tomorrow, but we’re building biomaterials, we just received two patents from the United States government on research we’ve been doing for over a decade, so that one day, we’ll actually not just restore singers, but we’ll be able to take many cancer patients and get their speaking voices back. That’s not something that’s going to take 10 or 20 years given how much we’ve done on this—I think it’s likely to occur under two years from now.

So it’s exciting stuff. Artists are willing to say, y’know, this is an athletic injury, and I was helped. And people shouldn’t ignore their voice. The overwhelming majority of things I have to remove and operate on to enhance someone’s voice have been there probably for over 10 years. People are scared to come in; they’re frightened they’re going to have something dangerous. And it’s getting younger and younger—I just had a 13-year-old child present to me with larynx cancer. So now people are getting vocal cord cancer who are not smokers, and that’s a change. So patients can create huge awareness—take someone like Tom Hamilton, the bass player for Aerosmith, he was open about it. He had chemo and radiation for throat cancer, and we used this newer technique six years ago, and he’s been cured, and he had an advanced lethal cancer.

Q: So you’ve worked with a wide range of artists, from opera singers to rock singers. Are there genres that are harsher on the voice?

Metal singers obviously—you’re screaming, that’s trauma. But most things singers get is just trauma. They go out and sing when they’re sick, they don’t want to let people down, the pressures of touring. Bleeding is very common, that was something Steve Tyler had, Adele had, Sam [Smith] had, Lionel had. I developed a newer approach about seven years ago with a specialized laser, which is also for cancer, which can stop the vocal bleeding and not burn the vocal cord at all—to the point that it can actually function better. Previously, it would cauterize them, and it would stiffen the cord. I think that changed the game: you have a precise way so singers didn’t have to be fearful that their voice would be ruined by treating the bleeding.

Q: Can you tell what kind of music your patients sing based on how they present symptoms?

Folks who have a little more trauma are musical theatre performers. The nature of what they do, they create a little more trauma because they’re higher pressure. But I can’t look at a set of vocal cords and say, ‘Ah, that’s what they do.’ There’s a lot of overlap.

Q: You’ve hinted at the fact that singers are fearful about this surgery because it’s their livelihood, their instrument, how they’ve defined themselves for much of their lives. Is that fear still a reality?

The very specialized issue is, ‘it’s not my knee, it’s my vocal cords.’ I think epople are getting more used to it in my view. It’s one of the outcomes that occurred when Julie Andrews’ procedure didn’t go well, this was this an initial procedure in New York I had nothing to do with. That was one of the most formidable voices of the late-20th century and after surgery she could no longer sing again. That creates fear. What I can say to you is that—that happened in the late 1990s, and I was able, with procedures, to enhance her voice but not to the point like it was the type of singing she could do before—but the fascinating thing was that when I was developing the procedures, people were learning about it from the late 90s to 2010s, what seemed to change thing substantially was the case with Adele. So many people knew about it, and she did quite well at the Grammys, and I thought that was very fortunate. In that time period was also when I helped Lionel Richie and Keith Urban and Paul Stanley of KISS, a whole range of people all of whom were realizing that the procedures were better. I think today, what ends up happening is that the real high-level fear, with what’s associated with Julie Andrews’ surgery, is diminished substantially. They’re realizing they’re athletes, and they might need restorative surgery, and tend to look today like it’s an opportunity to do better—not that you run to do it.

Q: I’m a big baseball guy, so when I think of the work you do, I think of Tommy John surgery in baseball—increasingly a reality for pitchers who have been throwing hard and frequently since they were young, and having this operation that can fix them, and arguably make them better and extend their career. Is that a fair comparison?

Yes and no. Here’s an example: Christina Perry has been a jewel, and she’s been so helpful, and she was transformed. She had a congenital cyst in her vocal cord and she didn’t know it. And when her career took off in her mid-20s, she was having trouble touring because she didn’t have the equipment, and I removed the cyst and she never had a problem again. More specifically with the Tommy John analogy, if you’ve been singing since you were 17 and now you’re in your 40s, and you got a lot of fame in your 30s and 40s, there’s going to be accumulated scars—and that can be regular scars, scars with vocal nodules, scars with vocal polyps—if this can be delicately removed, you put the tissues as if they’re younger. So it’s a kind of vocal rejuvenation, even though it isn’t really, you’re not rejuvenating the tissues, you’re just putting it closer to normal. And the remarkable thing is what separates the truly elite singers is their ability to continue to evolve and continue to become singers after the injury. The analogy I’d give you is Nolan Ryan pitching no-hitters when he was 40. He didn’t do it with a 102-mph fastball, he did it because he’s so good at what he does and knows the batters. So it’s a chance to use the experience you gained with a rearranged anatomy.

Of course, as I understand it, the Tommy John surgery also gives you a mechanical advantage, so pitchers sometimes do it volitionally, they want that advantage. But what we’re working toward with these biomaterials, that’s more like the Tommy John. What we do today is we remove things so vocal cords vibrate better. When we have these biomaterials, we’ll put it into the cords, which is the equivalent of rearranging the anatomy, and it’ll be just as important what you put in as you take out. The layer of the vocal cords that has to vibrate—we’ll be able to make it, and we can make it ultra-elastic. It’d be the equivalent of a pole vaulter going with less altitude. If we can control that, we can give them tissues that will let them sing later in life and with more precision.

Q: Tommy John is also controversial because it looks like a symptom—the idea that we’re pushing our kids to throw hard or too young, or not caring for their health with pre-emptive measures. Is that also the case with singers?

I think you need a coach who can help you discriminate the opportunities that are worthwhile. Most singers have to make judgment calls about their career, the kinds of gigs you have to do to advance your career. You need people who are loyal to you, not just the business of what you do, to make these kinds of decisions especially with young vocalists. Family is key there. But it’s a tension that’s always there.

Q: Is there an expectation, general rule, post-surgery?

Here’s an analogy: A woman could come in and they’re an aerobics instructor. It’s hard to be yelling loudly over the ambient music and the feet clomping and giving orders, and there’s a tendency for that population to have a husky voice and have vocal nodules. It’s not unusual to restore the vocal folds to what would be their typical vibratory pattern and have the woman say, ‘hey, you made me sound like a girl.’ Well, you are. There are characteristics that people use to manipulate the pathology—in other words, they use it for sound effects and like the husky sound. And if you have that and you’re fine, you don’t need the surgery. In summary, you have to remove pathologies for obvious reasons, and you have to work at sounding more husky. By overusing it you get a lump or a bump, and then you can use the lump or bump for a sound effect. There’s no one I know more talented than Steven Tyler who can use his vocal tissues in many different ways.

Singing is one of the most complicated brain functions there is. The motor wiring—the density of nerve fibres from the brain to the vocal cords is denser than anything in the human body. Nothing’s close. The face is a weak second; there’s probably 700 per cent less. So elite singing is probably the most complex motor task that human beings can do. It’s probably why society loves singers.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Update