Who will be the moonwalkers of tomorrow?

Colby Cosh on the future of our outer-space ambitions

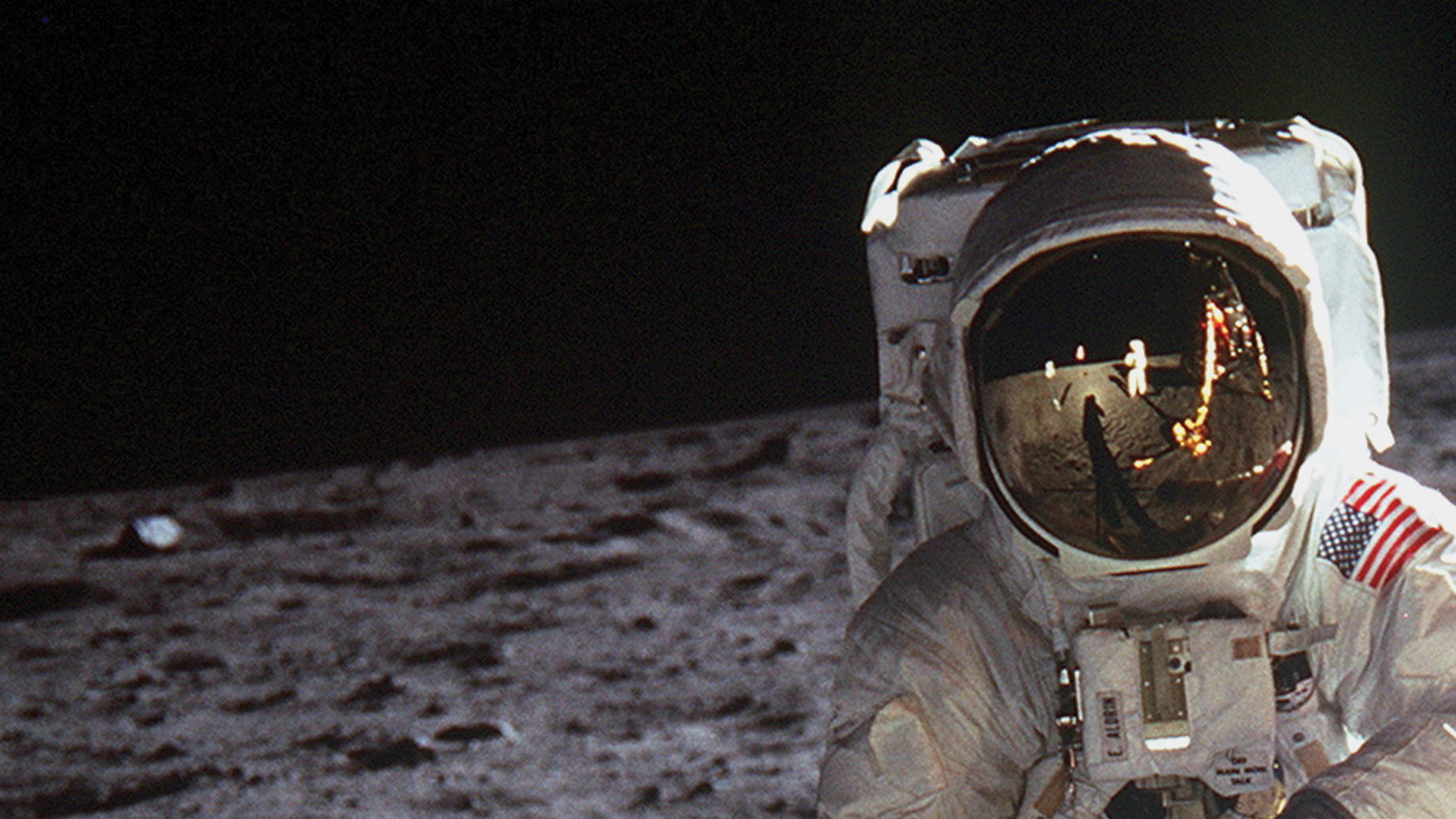

NASA/Getty Images

Share

It sometimes feels as though it took the world a generation to absorb humanity’s conquest of the moon. July 20 was the 45th anniversary of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin’s landing on the Sea of Tranquility. The date was, on this occasion, celebrated much more widely than I remember it being as a child space buff in the 1970s.

But, then, the story of spacefaring had not yet been interrupted. NASA had the Skylab space station in orbit and was readying the shuttle; Apollo 11 was just one step in a continuing outward journey. It was natural to expect that the dozen men who had walked on the moon would be joined by hundreds soon enough—and that eventually, as popular culture had been assuring us for 30 years, Luna would become a commercial colony of the United States, with pressurized underground hotels for tourists.

When Neil Armstrong died in 2012, we were suddenly made aware that the 12 moonwalkers—of whom eight remain—are an endangered species whose numbers have little hope of augmentation. It’s not just that nobody else is going to the moon any time soon: The very type of person we sent seems to be extinct. Today’s astronauts all have impressive academic and flying credentials, but the energy their predecessors put into war and deadly test piloting has been consumed with public-relations drills, and they come off more like schoolteachers than warriors.

This is part of what lets us regard the moon landing and the space dramas that bracketed it with something like the awe they deserve. Another factor, strangely enough, is the ubiquity of the electronic computer. The more dependent we become on devices, the harder it is for us to understand how men were sent to the moon using computers of inconceivable crudity—no more sophisticated than the pocket calculators of 1976.

The gulf that separates us from the near past is now so great that we cannot really imagine how one could design a spacecraft, or learn engineering in the first place, or even just look something up, without a computer and a network. Journalists my age will understand how profound and disturbing this break in history is: Do you remember doing your job before Google? It was, obviously, possible, since we actually did it, but how? It is like having a past life as a conquistador or a phrenologist.

The social and psychological explosiveness of the networked thinking machine can be seen in the ways in which we commemorate the moon landing. The 45th anniversary of Apollo 11 has features that were not present for, say, the 30th. One is the growth of conspiracy theories—not just their popularity, but their multiplicity. Poor Buzz Aldrin was told to his face so often that he was lying about going to the moon, he had to punch a guy to make it stop, and even that probably didn’t work. But others believe he did go—and that he saw aliens there. Or an Illuminati moonbase. Or the face of Satan. The various moon madnesses are a model of the way the Internet democratizes truth, whether in the form of history or news or scholarship or civics. Billions of ants, gnawing at the trunks of established narrative. Complete customized realities, set to electronic music and uploaded to YouTube.

But there is something else you’ll find on YouTube if you search for “moon landing”: clips of virtual-reality moon landings from a video game called Kerbal Space Program. I use “video game” as verbal shorthand, but “ballistics simulator” might be better. Kerbal Space Program allows you to build and man spacecraft and explore a fictional solar system with features like our own. Players have to deal with realistic gravitation, materials and pressures, and atmospheric effects. The “game” is not kidding around: Its complexity has made it popular at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and private rocketry outfits.

Which is to say that the line between a highly technical job and a pastime is becoming blurry. If you know (or are) a young person who plays Minecraft, Kerbal should remind you of it: an open-ended “game” that is really more of a toy universe. It is hard to escape the suspicion that people being raised on such recreations will be cognitively stronger than those of us who fumbled with Meccano sets. During the Cold War, a frightened America practically had to impress an army of young people into the discipline of physics. Now, tens of thousands train themselves on Newtonian orbital mechanics as a source of idle pleasure. If we ever do form a desire to return to the moon, we will have people who know the way.