Why can’t the FBI hack an iPhone?

An explainer on Tim Cook’s stand against a court order demanding Apple to create a ‘master key’ to unlock a terrorist gunman’s phone

An iPhone is seen in Washington, Wednesday, Feb. 17, 2016. A U.S. magistrate judge has ordered Apple to help the FBI break into a work-issued iPhone used by one of the two gunmen in the mass shooting in San Bernardino, California, a significant legal victory for the Justice Department in an ongoing policy battle between digital privacy and national security. Apple CEO Tim Cook immediately objected, setting the stage for a high-stakes legal fight between Silicon Valley and the federal government. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Share

Apple is refusing to help the FBI crack a locked iPhone belonging to San Bernardino gunman Syed Rizwan Farook. Yesterday, following a court order compelling the tech company to assist law enforcement agents, Apple chief executive Tim Cook published a statement damning the request as a “dangerous precedent.”

But why does the FBI—part of the same government that built Stuxnet, the world’s first digital weapon—even need help to unlock an iPhone?

Why can’t the FBI hack into the phone?

The only way into an iPhone is through the four-to-six-digit front door—the passcode. Most of the information on the device is encrypted, and punching in that number (or flashing your fingerprint) initiates the decryption process.

To learn the password and unlock the phone, the FBI wants to use a “brute force” attack—rapidly attempting number combinations until it stumbles on the correct one. However, three things stand in the FBI’s way:

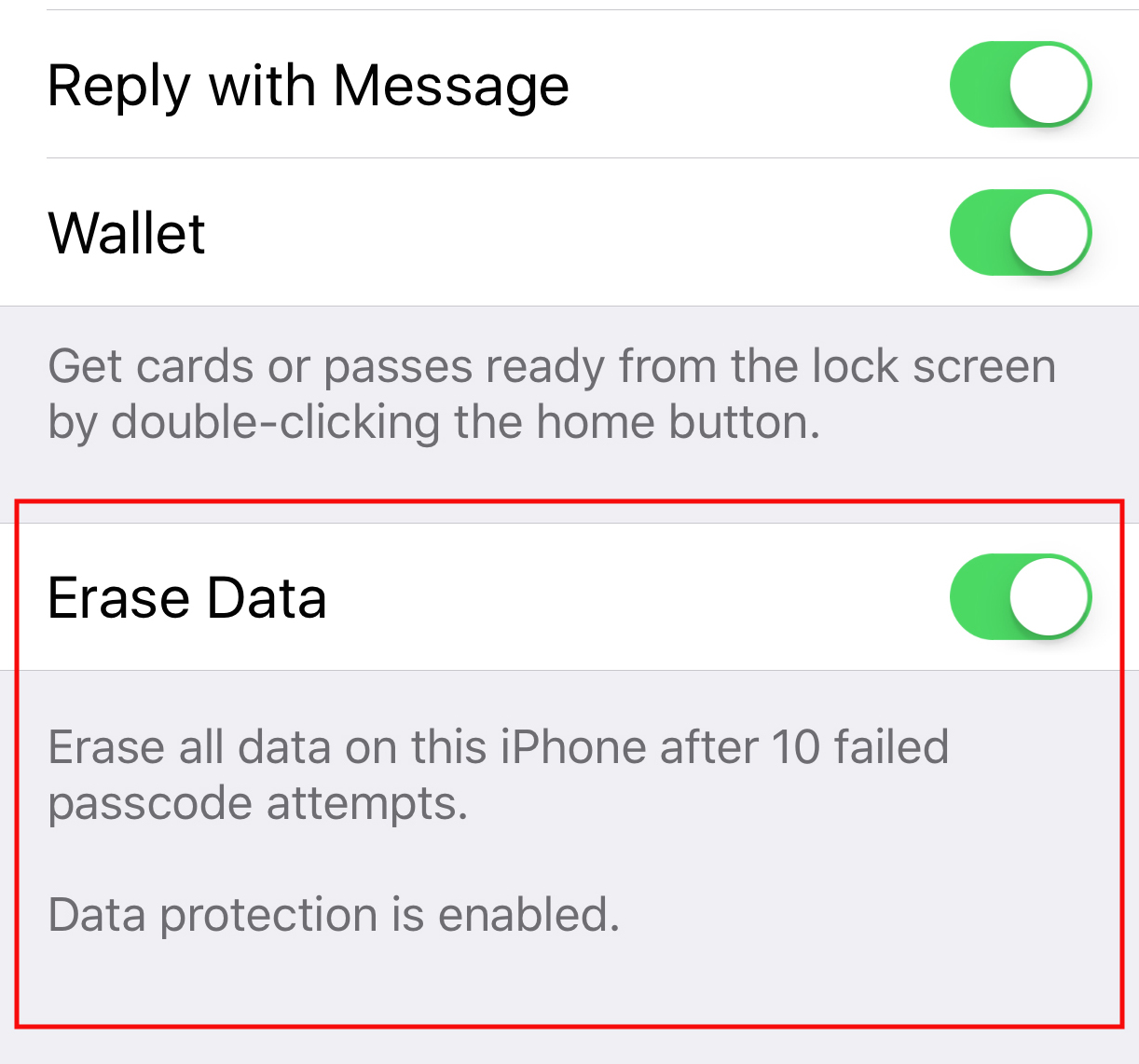

– Entering an incorrect password 10 times consecutively will automatically erase the phone’s data (if the “data erase” option is enabled)

– Passcodes must be entered by hand, one at a time

– The Apple operating system introduces a delay after every incorrect password attempt

What does the FBI want Apple to do?

The FBI has requested that the company develop a way to offer federal investigators unlimited attempts at accessing the phone’s data—without the risk of erasing it. Only Apple has the digital keys necessary to force an iPhone to accept such a firmware update, which is why the FBI can’t do this on its own.

The FBI wants Apple to create a special version of their operating system that:

– Disables the 10-strikes-and-you’re-out safeguard

– Disables passcode-entry delays

– Allows the FBI to connect an external device that helps crack the passcode. That would avoid manually inputting 10,000 possible combinations (and that’s only if Farook used a four-digit passcode. There are a million combinations of six digits!)

Why is Apple refusing?

In his Feb. 16 statement to the public, Cook says the request is “something we consider too dangerous to create.” The FBI’s demand for a backdoor into the iPhone would not only provide the government with a way to unlock Farook’s phone, but allow for the potential development of ways to undermine security features in all iPhones.

“While the government may argue that its use would be limited to this case, there is no way to guarantee such control,” wrote Cook. “Once created, the technique could be used over and over again, on any number of devices. In the physical world, it would be the equivalent of a master key, capable of opening hundreds of millions of locks.”

Related: Jameel Jaffer on the hard fight to make America care about privacy issues

Can Apple even do what the FBI asks?

While Apple doesn’t hold the key to directly unlocking the phone, they potentially have the ability to make changes to the phone’s operating system that would allow the FBI to pick the lock using brute force.

“It’s difficult to say with any degree of certainty—Apple does not disclose enough about its operating system to know,” says a cybersecurity expert interviewed by the BBC.

Dan Guido of the security company Trail of Bits, however, believes that the request is possible—but only because the phone in question is an iPhone 5C, which lacks an additional complex security feature called the Secure Enclave.

“If the San Bernardino gunmen had used an iPhone with the Secure Enclave, then there is little to nothing that Apple or the FBI could have done to guess the passcode,” he writes on the company blog.

How can the courts demand this?

The courts are using the All Writs Act, an 18th-century law that compels a party to help the government in its law enforcement efforts. Apple argues that the judge’s demand represents an “unprecedented use” of the act.

A similar case is before the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York. In that case, the judge has yet to decide whether the government can use the All Writs Act to compel Apple to unlock the iPhone.