Will virtual body swapping reduce racism in America?

Researchers use virtual reality to expose white Americans to systemic racism faced by people of colour

(Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Maister et al.)

Share

There are at least two ways to walk from Harlem to Soho: as a white person, and as a black person. With research on “virtual body swapping,” in which participants use a virtual reality headset to enter a body of different race, Americans can wear both pairs of shoes.

“In Harlem, they’ll see the sheer volume of police standing on a corner on just your average Saturday afternoon,” says Courtney Cogburn, an assistant professor of social work at Columbia University. Although white participants might have noticed the police anyway, their experiences as black avatars will make them better understand “the racism that’s in the air,” she says. “It’s ambient.”

Beginning in September, and partnering with Stanford University in a $250,000 research project, Cogburn will equip white people with a virtual reality headset and motion tracking suit. Participants, including supporters of Bernie Sanders, Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, will operate a black avatar as they walk through a virtual New York City, hopefully better understanding systemic racism. Given the recent shootings in Louisiana and Minnesota, in which two white police officers each killed black citizens, Cogburn says this intervention “could certainly be applied to police.” Despite the retaliation in Dallas, where black protestors killed five white officers, the research will not introduce black people into virtual white bodies.

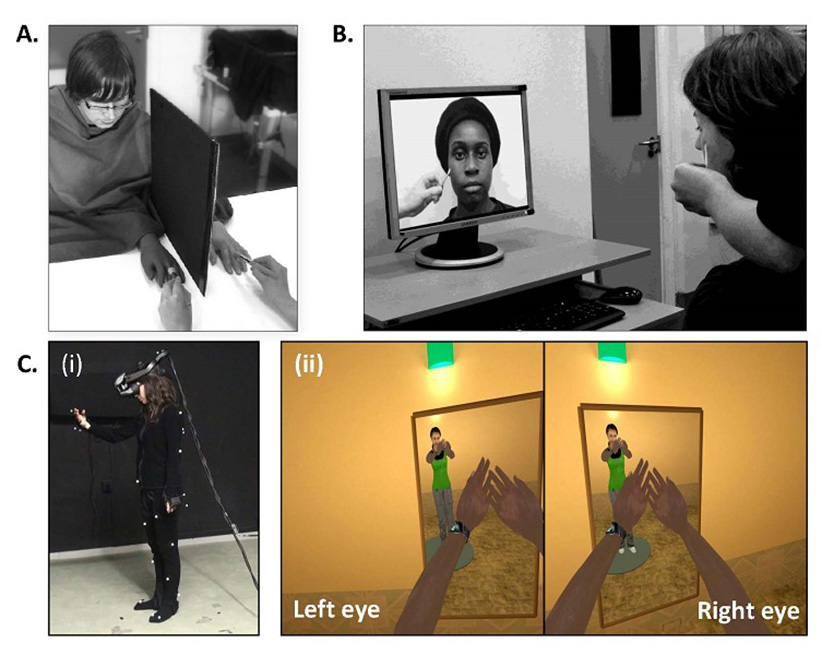

Cogburn’s team will be the first to take virtual body-swappers into a virtual real-world setting, she says. Since 2009, Stadford’s Virtual Human Interaction Lab has put body-swappers in a neutral setting, where they operate avatars of different races and simply look around a room. The goal has been to improve empathy. After just this five-minute experience, participants showed less white preference on an implicit association test, which measures how they associate words such as “love” and “evil” with race.

Body-swapping has proven more effective than simply imagining oneself as another race. In fact, when Stanford researchers asked students to imagine a day in the life of a black person, including attending a job interview, these participants afterward showed more white preference because they had imagined, or “activated,” stereotypes. In similar research related to age, Stanford has gotten participants to virtually enter older versions of themselves, reducing ageism and increasing motivation for financial planning.

Europeans have also used body-swapping to boost empathy between races. Mel Slater, a computer science professor specializing in virtual environments at the University of London, explains that white participants in a neutral setting quickly identify with their virtual black avatars. “People don’t go, ‘Wow, I’ve got a black body!’” he says. “They just take it. It just is … The most interesting thing is that nothing interesting happens.”

Virtual body-swapping works by tricking the participant’s brain into viewing the avatar as itself. “The brain doesn’t like uncertainty or confusion,” says Slater. “It tries to come up with answers. The simplest thing it can come up with is that it’s my body.” Slater’s team found that the empathy isn’t just temporary. One week after the body swap, participants maintained lower white preference scores, and Slater expects the effect might last even longer.

The ethics of changing people’s mindsets are unclear. Slayter says virtual body-swapping could be incorporated into games that are designed for general employee or police training. Ideally, white participants would have black avatars, unaware of the intent to increase empathy. “It’s better if the purpose isn’t explicit,” says Slater. However, “if they’re surreptitiously altering people’s attitudes, people would find ethical problems with that.”

Virtual reality holds other limitations. It can make people dizzy, and Slater doesn’t recommend it for children under age 13, as neurologists don’t yet understand how it might affect developing brains. Some say citizens could better develop empathy by spending time with real people of other races, rather than playing around with avatars. Further, in video games, the assignment of racialized avatars has proven to worsen prejudice. When the developers of a game called Rust randomly assigned white players to have black avatars, gamers posted racist rants on blogs, with one declaring, “if I’m black I’m asking for a refund.”

Cogburn says virtual body-swapping can supplement efforts to build real-world bridges, as many Americans don’t naturally spend time with people of other races. She says the real-world setting won’t worsen prejudice because the purpose of her project is to help people recognize racism, not necessarily feel it. “I’m still questioning whether empathy is the goal or if it really is possible,” she says. “What might be more important is to try to understand [racism].” Participants will have nothing at stake, not even points in a video game, as they walk through New York City—its neighbourhoods, its prejudices and its police officers. “It’s a vicarious observation of these things,” says Cogburn. “It’s not actually happening to you, and that’s the point.”