The First World War’s forgotten Southern Front

The latest in our monthly series looking at 1916, the year that marked the point of no return in the First World War

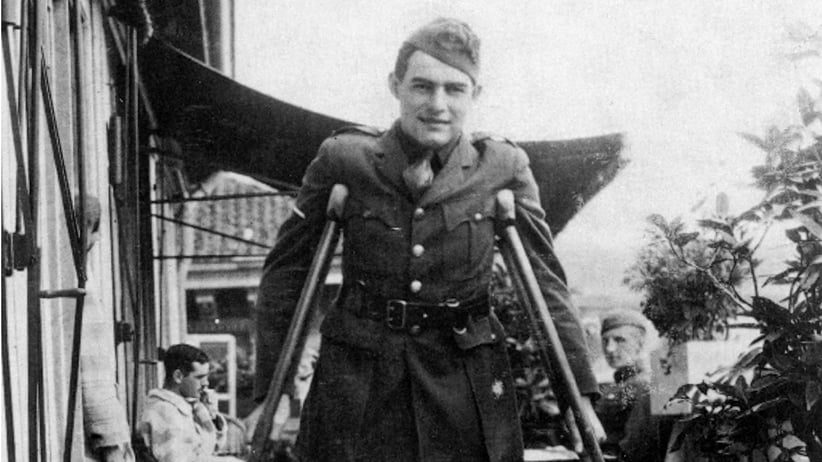

Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961) american novelist here during his convalescence in Milan, Italy, 1918. (Apic/Getty Images)

Share

To commemorate the centennial of 1916—an under-recognized turning-point year in world history—Brian Bethune will write a story highlighting a crucial event. Click here to read other entries in this monthly series.

With the notable exception of Gallipoli-fixed Australians and New Zealanders, the focal point of the English-speaking world’s historical memory of the First World War is the Western Front, the cauldron that consumed most of its war dead. There’s very little room in that memory for even the Eastern Front, except as a key contributor to the Russian Revolution, and virtually none for the Southern, the March subject of Irish historian Keith Jeffrey’s month-by-month 1916: A Global History. (See here for earlier months.) There, on a 600-km stretch of territory leading from mountaintops to more conventional battlefields near the Adriatic coast, Germany’s ramshackle ally, the Austro-Hungarian Hapsburg Empire faced off against the Western alliance’s weak sister, Italy.

Were it not for A Farewell to Arms, Ernest Hemingway’s novel based on his service on the Southern Front as an 18-year-old ambulance driver, it’s likely North America’s popular memory would have no room at all for a theatre of war where the casualties exceeded 1.3 million. That’s not only a tribute to the power of art, but a reflection of how grotesquely banal the war had become by 1916. Aside from the innovative use of avalanches as weapons of war—the two sides deliberately fired artillery barrages into the snowpack, killing 10,000 soldiers in December 1916 alone—the Italian Front was the quintessential demonstration of historian John Gooch’s summation that the war had become “instinctual,” rather than based on any rational or even emotional calculation of national interest.

In truth, although Jeffrey chose March to highlight the Italian Front, he could have shoehorned one of its endless, almost identical battles into almost half of 1916—there were 12 battles in all between June 1915 and November 1917. Five, from the fifth to the ninth engagement, were fought in 1916, and the fifth battle of the Isonzo River, March 9 to 17, is as representative as any. But no more than any other, and Jeffrey freely draws from the others to show what the Great War was doing to two belligerents whose institutions could not withstand the strain.

The Italian army, even more than French troops at Verdun, “were as much at risk from the actions of their own side as from anything the enemy might throw at them,” writes Jeffrey, and not just from friendly fire. The Italians had the most draconian military discipline of any belligerent. The state police, the Carabinieri had a line of posts behind the front from which they emerged authorized to shoot soldiers failing to obey orders; one army doctor’s records from November 1915 records 80 casualties from enemy machine-gun fire and 25 “shot in the buttocks by the Carabinieri.” By May 1916 the Italian high command was ordering decimations—in one case, after four companies had attempted to surrender, two men were selected by lot from each contingent and summarily shot. As for the Hapsburg forces, they exhibited their usual inability to communicate with each other, or with their captors for that matter: A British volunteer nurse noted her surprise when she found that of six wounded prisoners given over to her care, only one could speak even a few words of German.

The war, and the polarizing forces of nationalism that the old regimes could no longer bottle up, famously destroyed the Austro-Hungarian Empire. But it also fatally weakened Italy, despite that country being on the winning side. It was in the war for the territory it hoped to gain, but its minimal military success meant the Treaty of Versailles provided only crumbs. The bitterness of aggrieved Italian nationalists would become a major factor in fuelling the grand dreams of fascism, and Mussolini’s easy seizure of power in 1922. The six-decade-old Kingdom of Italy survived the seven-century-old Hapsburg dynasty by only four years.