The last days of the hockey brawler

Hockey is evolving—and the thirst for victory once again trumps the fans’ thirst for blood

Jarred Tinordi #24 of the Montreal Canadiens fights with Cody McLeod #55 of the Colorado Avalanche in the NHL game at the Bell Centre on October 18, 2014 in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. (Francois Lacasse/NHLI/Getty Images)

Share

It’s hard to argue against hockey fighting without sounding like you’re leading a seminar in applied ethics. No matter how deep your roots in the game, or how compelling your rationale, you invariably come off as the sort of chin-stroking moralist that folks watch hockey to get away from.

What kind of sport, you ask, exposes its fans with periodic sideshows of bare-knuckle fisticuffs? A great one! How can the NHL, in good conscience, cash in on fighting while exposing its players to perils that have nothing to do with putting the puck in the net? Who cares? Everyone involved—owners, players and fans—has entered the bargain with eyes wide open. Conn Smythe, the legendary former Toronto Maple Leafs GM, might have summed up best the game’s imperviousness to anti-fighting scolds: “Any more of this brawling,” he purportedly cracked, “and we’ll have to print more tickets.”

Now, as the NHL enters its 98th season, there’s change in the arena air. Fighting in the league is on the decline, even as blood sports like mixed martial arts have carved a place in the societal mainstream. Battle-hardened knuckle chuckers are being pushed out of the NHL, while those who do fight are compelled to show they have more tools in their kit than their fists. “We went through a phase where you had guys who could intimidate but do nothing else,” says John Shannon, an NHL analyst on Sportsnet TV and a former executive producer of Hockey Night in Canada. “That phase is coming to an end.”

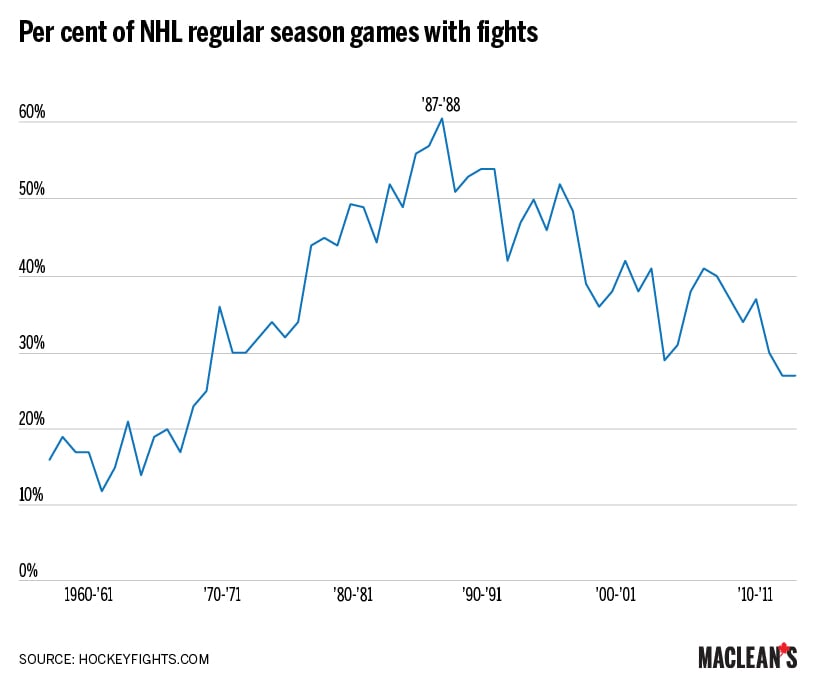

With a whimper, it seems, rather than a bang. Few hardcore fans seemed to notice last year as the share of games in which fights occurred dipped below 27 per cent, down about a third from averages seen in the 2000s, and far below those of the late 1980s, when marauders like Basil McRae, John Kordic and Joey Kocur roamed the ice (HockeyFights.com, the statistical authority on this subject, deems a fight to have happened if referees assess at least one fighting major).

Only 45 of 1,230 games last year featured multiple fights, while the season’s most prolific pugilists dropped the gloves nowhere near as often as their forebears. Colorado Avalanche forward Cody McLeod topped the league with 19 scraps, but that number paled next to the 35 per year routinely racked up by the mullet-headed warriors of the ’80s and early ’90s. Statistically speaking, the NHL hasn’t been this peaceful since Bobby Orr was a rookie.

How did this happen? It doesn’t seem long ago, after all, that NHL commissioner Gary Bettman was channelling Smythe (albeit in more lawyerly terms) when asked about the dangers posed by fighting. “Our fans,” he said at an all-star game in 2009, “tell us that they like the level of physicality in our game.”

We shouldn’t discount the effect of broad-based cultural shifts, says Shannon. Hockey has been dragged into the 21st century, with prominent players speaking out against racism, homophobia and, more recently, bullying and violence at the amateur level, he notes. But coaches and managers are a lot less responsive to social currents than to competitive pressure, he says, which in recent years has punished teams that relied on intimidation. “This is a copycat league,” says Shannon, “and right now every coach wants to run four lines. Shifts have shortened, the pace has sped up and your fourth-line guys have to be able to play 10 minutes a game. There’s no room anymore for the fighter who plays five minutes a night.”

Indeed, you might soon see them on the endangered species list. Some, like Colton Orr (Toronto) and George Parros (last with Montreal) have been pushed out of the game in the last couple of years, while others, including Anaheim’s Brian McGrattan and Arizona’s John Scott, have been forced to settle for bargain-basement contracts from which they can be easily released. Columbus’s Jared Boll, the league’s fourth-most prolific fighter in 2014-15, came close to having his contract bought out after averaging 7:16 in ice time a game last year. He spent the off-season getting leaner and working on his speed in hopes of securing one of the last spots in the Blue Jackets’ lineup.

But to survive much longer, he might need to change his DNA, because players like him are up against third and fourth liners who have much more to their games. Of the five most frequent fighters last season, all but Boll reached double digits in ice time, and several were key cogs in their teams’ lineups. McLeod, a seven-year veteran, averaged 11:11 in ice time per game while pitching in a respectable seven goals (Boll scored one). Brandon Prust, traded by Montreal this summer to Vancouver, fights, kills penalties, forechecks and, when needed, takes faceoffs. In Ottawa, defenceman Mark Borowiecki racked up 13 fights yet played a vital 16 minutes a night on the Senators’ blue line.

To David Singer, the founder and keeper of HockeyFights.com, those numbers suggest fighting is maintaining its place in the sport by changing its nature. Such players safeguard their teammates with gusto, he notes, “but you probably wouldn’t give those guys the same label you might have 10 or 20 years ago, like ‘enforcer.’ You’d simply refer to them as tough players.” That’s because few engage in the sort of pre-arranged fights common among designated goons, says Singer, where the players converge at an agreed-upon time of the game and drop their gloves.

Such demonstrations of brawn—once thought to discourage cheap shots against more talented players—are giving way to spontaneous fights arising from in-the-moment confrontations, or score-settling bouts linked to incidents that might have occurred a shift or two earlier. It bears more resemblance to enforcement as done in the age of John Ferguson and Ted Green. For lack of a better term: the organic hockey fight.

As a matter of player safety, that’s probably good news. Over the past five years, an alarming number of NHL tough guys have succumbed to some combination of physical and mental ailments—most recently Todd Ewen, a former career fighter who committed suicide two weeks ago. A class-action suit filed against the league by retired players cites a growing body of science linking concussions with depression, mental illness and permanent brain damage. With that in mind, it’s tempting to think NHL owners and GMs are hedging against the possibility they’ll wind up in front of a civil jury. Knowing the potential risk, how could they justify signing players to do nothing but rain blows on each other’s heads?

Shannon doubts it. “Managers, coaches and owners are really more committed to winning than anything,” he says. “I think the way Conn Smythe ran the Maple Leafs is the same way [owner] Ted Leonsis runs the Washington Capitals today—to put up points.” That’s a revealing comparison, suggesting not only that hockey is evolving by reverting to earlier form, but that the thirst for victory has trumped fans’ thirst for blood. If the competitive urge has taken a bite out of fighting, it has achieved what no principled argument ever did.