The lonely death of Chanie Wenjack

Chanie was 12, and Indigenous. He died as the white world’s rules had forced him to live—cut off from his people.

Chanie Wenjack. (The Wenjack Family)

Share

In 1967, Maclean’s told the tragic tale of Chanie Wenjack, an Indigenous boy who died after running away from his residential school in northern Ontario. Gord Downie had explained that this story is the inspiration for his Secret Path project. The frontman of the Tragically Hip worked with Toronto illustrator Jeff Lemire on Secret Path, which includes an album, graphic novel and animated film. We have republished that cover story below in its original form, in which Chanie’s teachers misnamed him Charlie.

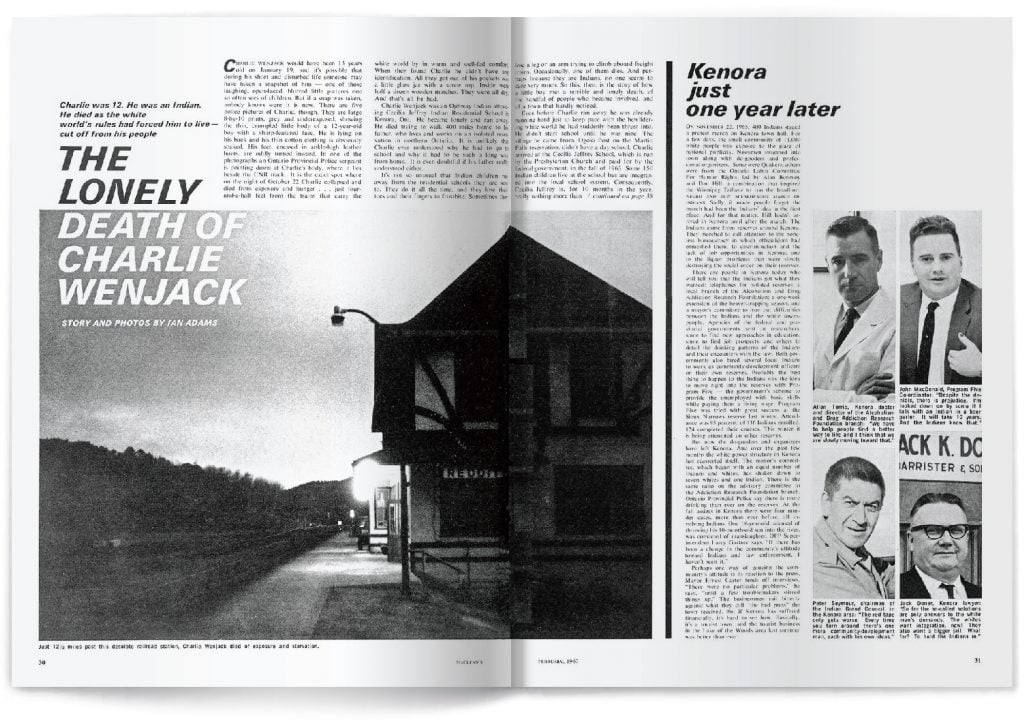

CHARLIE WENJACK would have been 13 years old on January 19, and it’s possible that during his short and disturbed life someone may have taken a snapshot of him — one of those laughing, open-faced, blurred little pictures one so often sees of children. But if a snap was taken, nobody knows where it is now. There are five police pictures of Charlie, though. They are large 8-by-10 prints, grey and underexposed, showing the thin, crumpled little body of a 12-year-old boy with a sharp-featured face. He is lying on his back and his thin cotton clothing is obviously soaked. His feet, encased in ankle-high leather boots, are oddly turned inward. In one of the photographs an Ontario Provincial Police sergeant is pointing down at Charlie’s body, where it lies beside the CNR track. It is the exact spot where on the night of October 22 Charlie collapsed and died from exposure and hunger . . . just four-and-a-half feet from the trains that carry the white world by in warm and well-fed comfort. When they found Charlie he didn’t have any identification. All they got out of his pockets was a little glass jar with a screw top. Inside were half a dozen wooden matches. They were all dry. And that’s all he had.

CHARLIE WENJACK would have been 13 years old on January 19, and it’s possible that during his short and disturbed life someone may have taken a snapshot of him — one of those laughing, open-faced, blurred little pictures one so often sees of children. But if a snap was taken, nobody knows where it is now. There are five police pictures of Charlie, though. They are large 8-by-10 prints, grey and underexposed, showing the thin, crumpled little body of a 12-year-old boy with a sharp-featured face. He is lying on his back and his thin cotton clothing is obviously soaked. His feet, encased in ankle-high leather boots, are oddly turned inward. In one of the photographs an Ontario Provincial Police sergeant is pointing down at Charlie’s body, where it lies beside the CNR track. It is the exact spot where on the night of October 22 Charlie collapsed and died from exposure and hunger . . . just four-and-a-half feet from the trains that carry the white world by in warm and well-fed comfort. When they found Charlie he didn’t have any identification. All they got out of his pockets was a little glass jar with a screw top. Inside were half a dozen wooden matches. They were all dry. And that’s all he had.

Charlie Wenjack was an Ojibway Indian attending Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School in Kenora, Ont. He became lonely and ran away. He died trying to walk 400 miles home to his father, who lives and works on an isolated reservation in northern Ontario. It is unlikely that Charlie ever understood why he had to go to school and why it had to be such a long way from home. It is even doubtful if his father really understood either.

It’s not so unusual that Indian children run away from the residential schools they are sent to. They do it all the time, and they lose their toes and their fingers to frostbite. Sometimes they lose a leg or an arm trying to climb aboard freight trains. Occasionally, one of them dies. And perhaps because they are Indians, no one seems to care very much. So this, then, is the story of how a little boy met a terrible and lonely death, of the handful of people who became involved, and of a town that hardly noticed.

Even before Charlie ran away he was already running hard just to keep pace with the bewildering white world he had suddenly been thrust into. He didn’t start school until he was nine. The village he came from, Ogoki Post on the Martin Falls reservation, didn’t have a day school. Charlie arrived at the Cecilia Jeffrey School, which is run by the Presbyterian Church and paid for by the federal government, in the fall of 1963. Some 150 Indian children live at the school but are integrated into the local school system. Consequently, Cecilia Jeffrey is, for 10 months in the year, really nothing more than an enormous dormitory. And Charlie, who understood hardly any English, spent the first two years in grade one. He spent last year in what is called a junior opportunity class. That means he was a slow learner and had to be given special instruction in English and arithmetic. This fall he wasn’t quite good enough to go back into the grade system, so he was placed in what is called a senior opportunity class. But there was nothing stupid about Charlie. His principal of last year, Velda MacMillan, believed she got to know him well. “The thing we remember most about him was his sense of humor. If the teacher in the class made a joke, a play on words, he was always the first to catch on.”

Charlie wasn’t a strong boy. In fact, he was thin and sickly. He carried an enormous, livid scar that ran in a loop from high on his right chest, down and up over his back. It meant that in early childhood his chest had been opened. Nobody knows exactly when. “Indian children’s early medical records are practically impossible to track down,” explains Kenora’s public-health doctor, P. F. Playfair. The postmortem that was later performed on Charlie by Dr. Peter Pan. of Kenora, showed that his lungs were infected at the time of his death.

On the afternoon of Sunday, October 16, when Charlie had only another week to live, he was playing on the Cecilia Jeffrey grounds with his two friends, Ralph and Jackie MacDonald. Ralph, 13, was always running away —three times since school had started last fall. Jackie, only 11, often played hooky. In the three years he had been at the school Charlie had never run away. He had played hooky for one afternoon a week earlier, and for that he had been spanked by the principal, Colin Wasacase.

Right there on the playground the three boys decided to run away. It was a sunny afternoon and they were wearing only light clothing. If they had planned it a little better they could have taken along their parkas and overshoes. That might have saved Charlie’s life.

Slipping away was simple. The school, a bleak institutional building, stands on a few acres on the northeast outskirts of Kenora. For the 75 girls and 75 boys there are only six supervisors. At that time the staff were all new and still trying to match names to faces. (That same day nine other children ran away. All were caught within 24 hours.)

As soon as they were clear of the school, the three boys hit that strange running walk with which young Indian boys can cover 10 miles in an hour. They circled the Kenora airfield and struck out north through the bush over a “secret trail” children at the school like to use. The boys were heading for Redditt, a desolate railroad stop on the CNR line, 20 miles north of Kenora and 30 miles east of the Manitoba border. Because Charlie wasn’t as strong as the others, they had to wait often while he rested and regained his strength. It was on the last part of this walk, probably by the tracks, that Charlie picked up a CNR schedule with a route map in it. In the following days of loneliness that map was to become the focus of his longings to get back to his father. But in reality the map would be never more than a symbol, because Charlie didn’t know enough English to read it.

It was late at night when the three boys got to Redditt: it had taken them more than eight hours. They went to the house of a white man the MacDonald brothers knew as “Mister Benson.” Benson took the exhausted boys in, gave them something to eat, and let them sleep that night on the floor.

Early the next morning the boys walked another half mile to the cabin of Charles Kells. The MacDonald boys are orphans — their parents were killed in a train accident two years ago. Kelly is their uncle and favorite relative. Kelly is a small man in his 50s. When he talks he has a nervous habit of raking his fingers through his grey, shoulder-length hair. Like most of the Indians in the area, he leads a hard life and is often desperately hungry. It’s obvious he cares about his nephews. “I told the boys they would have to go back to school. They said if I sent them back they would run away again. I didn’t know what to do. They won’t stay at the school. I couldn’t let them run around in the bush. So I let them stay. It was a terrible mistake.”

That same morning Charlie’s best friend, Eddie Cameron, showed up at the Kelly cabin. He, too, had run away from the school. Eddie is also a nephew of Kelly’s. This gathering of relations subtly put Charlie Wenjack out in the cold. The Kellys also had two teenage daughters to feed and Kelly, who survives on a marginal income from welfare and trapping, probably began to wonder exactly what his responsibility to Charlie was. Later he and his wife Clara would refer to Charlie as “the stranger.” The Kellys had no idea where Charlie’s reserve was or how to get there.

“He was always looking at this map,” said Mrs. Kelly, “and you couldn’t get nothing out of him. I never seen a kid before who was so quiet like that.”

Nobody told Charlie to go. Nobody told him to stay either. But as the days passed Charlie got the message. So it must have been with a defiant attempt to assert his own trail existence that he would take out his map and show it to his friend Eddie Cameron, and together they would try to make sense out of it. And Charlie would tell Eddie that he was going to leave soon to go home to his father. But as Eddie remembers. Charlie only knew “his dad lived a long way away. And it was beside a lot of water.’

On Thursday morning Kelly decided he would take his three nephews by canoe up to his trapline at Mud Lake, three miles north of Redditt. “It was too dangerous for five in the canoe.” said Kelly, “so I told the stranger he would have to stay behind.”

Charlie played outside for a while, then he came in and told Mrs. Kelly he was leaving and he asked for some matches. Nobody goes into the bush without matches. If the worst comes to the worst you can always light a fire to keep warm. Mrs. Kelly gave him some wooden matches and put them in a little glass jar with a screw cap so they would keep dry. She also gave him a plateful of fried potatoes mixed with strips of bacon. Then he left. “I never seen him again,” said Clara Kelly.

Nobody will know whether Charlie changed his mind about leaving or whether he wanted to see his friends one last time, but instead of striking out east along the railroad tracks, he walked north to Mud Lake, arriving at the cabin by the trapline before Kelly and his nephews got there in the canoe. That night all there was to eat were two potatoes. Kelly cooked and divided them among the four boys. He didn’t eat anything himself but he drank some tea with the others. In the morning there was only more tea. Kelly told Charlie he would have to walk back because there was no room in the canoe. Charlie replied that he was leaving to go home to his father. “I never said nothing to that,” says Kelly. “I showed him a good trail down to the railroad tracks. I told him to ask the sectionmen along the way for some food.”

But Charlie didn’t ask anyone for anything. And though he stayed alive for the next 36 hours, nobody saw him alive again.

When he left Kelly and his nephews and set out to walk home to his father. Charlie had more than half of northern Ontario to cross. There are few areas in the country that are more forbidding. The bush undulates back from the railroad tracks like a bleak and desolate carpet. The wind whines through the jackpines and spruce, breaking off rotten branches, which fall with sudden crashes. The earth and rocks are a cold brown and black. The crushed-rock ballast, so hard to walk on, is a pale-yellow supporting ribbon for the dark steel tracks. Close to the tracks, tall firs feather against a grey sky. And when a snow squall comes tunnelling through a rock cut it blots out everything in a blur of whiteness. The sudden drop in temperature can leave a man dressed in a warm parka shaking with cold.

All Charlie had was a cotton windbreaker. And during those 36 hours that Charlie walked, there were snow squalls and freezing rain. The temperature was between –1° and –6° C. It is not hard to imagine the hopelessness of his thoughts. He must have stumbled along the tracks at a painfully slow pace — in the end he had covered only a little more than 12 miles. He probably spent hours, huddled behind rocks to escape the wind, gazing at the railroad tracks. Somewhere along the track he lost his map or threw it away. Charlie must have fallen several times because bruises were found later on his shins, forehead and over his left eye. And then at some point on Saturday night, Charlie fell backward in a faint and never got up again. That’s the position they found him in.

At 11:20 a.m. on Sunday, October 23, engineer Elwood Mclvor was bringing a freight train west through the rock cut near Farlane, 12 1/2 miles east of Redditt. He saw Charlie’s body lying beside the track. An hour later a section crew and two police officers went out to bring Charlie’s body back.

“It’s a story that should be told,” said the section foreman, Ed Beaudry. “We tell this man he has to send his son to one of our schools, then we bring his boy back on a luggage car.”

The Sunday they went to pick up Charlie’s body, intermittent snow and sleet blew through Kenora’s streets. The church services were over, and the congregations from Knox United Church and the First Presbyterian Church, which face each other at Second Street and Fifth Avenue, were spilling out onto the sidewalks. Just two blocks west at Second and Matheson I walked into a hamburger joint called the Salisbury House. An Indian woman in an alcoholic stupor was on her hands and knees on the floor, trying to get out the door. None of the half-dozen whites sitting at the counter even looked at her. A young well-dressed Indian girl came in and, with a masklike face, walked around the woman on the floor. The girl bought a pack of cigarettes, and then on the way out held the door open for the woman, who crawled out on her hands and knees and collapsed on the sidewalk.

One man at the counter turned and looked at the woman. “That’s what they do to themselves,” he said in a tone of amused contempt.

The kid behind the counter suddenly turned whitefaced and angry, “No, we did,” he said.

“We? No, it was the higher-ups, the government,” replied the man.

“No,” insisted the kid, “it was you, me, and everybody else. We made them that way.”

The men at the counter looked at him with closed, sullen faces. The kid wouldn’t give me his name. “I just work here part-time,” he said. “I work for the highways department . . .I guess I’ll have to learn to keep my mouth shut. Because nothing ever really changes around here.”

Charlie Wenjack finally did go home — the Indian Affairs Department saw to that. They put him in a coffin and took him back to Redditt and put him on the train with his three little sisters, who were also at the Cecilia Jeffrey School. Colin Wasacase, the principal, went along with them, too. Wasacase, in his early 30s, is a Cree from Broadview, Sask. He knows what Indian residential schools are all about. He has lived in them since he was a child, and taught in them. He was at one such school at the age of six when he broke his left arm. The arm turned gangrenous and was amputated.

At Sioux Lookout the little party picked up Charlie’s mother. She was taking tests for a suspected case of TB. From Nakina they all flew 110 miles north to Ogoki. It’s the only way you can get to Charlie’s home.

Charlie’s father, grief-stricken, was bewildered and angry as well. In his 50s, he is known as a good man who doesn’t drink and provides well for his family. He buried Charlie, his only son, in the tiny cemetery on the north shore of the Albany River. He has decided not to send his daughters to school but to keep them at home. Wasacase understands that, too. His own parents kept him out of school for two years because another boy in the family died much the same way Charlie did.

There’s not much else to say about Charlie Wenjack, except that on November 17 an inquest was held in the Kenora Magistrate’s Court. Most of the people who have been mentioned in this story were there. The coroner, Dr. R. G. Davidson, a thin-lipped and testy man, mumbled his own evidence when he read the pathologist’s report, then kept telling the boys who ran away with Charlie to speak up when answering the Crown attorney’s questions. When Eddie Cameron, Charlie’s best friend, entered the witness box, Davidson unnerved Eddie with warnings about telling the truth and swearing on the Bible. “If you swear on that book to tell the truth, and you tell lies, you will be punished.” Which seemed unnecessary because, as Crown Attorney E. C. Burton pointed out, a juvenile doesn’t have to be sworn in at an inquest. Eddie later broke down on the stand and had to be excused. Davidson let Burton deal with the boys after that. Burton was gentle enough, but the boys were withdrawn and for the most part monosyllabic in their answers.

“Why did Charlie run away?”

Silence.

“Do you think it was because he wanted to see his parents?”

“Yeah.”

“Do you like the school?”

“No.”

“Would you rather be in the bush?”

“Yeah.”

“Do you like trapping?”

“Yeah.”

Before the boys were questioned, the constable in charge of the investigation, Gerald Lucas, had given the jury a matter-of-fact account of finding Charlie’s body. In telling it simply, he had underlined the stark grimness of Charlie’s death. But it was now. through the stumbling testimony of the boys, and in the bewildered silences behind those soft one-word answers, the full horror began to come out. No, they didn’t understand why they had to be at the school. No, they didn’t understand why they couldn’t be with their relatives. Yes, they were lonesome. Would they run away again? Silence. And the jury was obviously moved. When Eddie Cameron began to cry on the stand, the jury foreman, J. R. Robinson, said later, “I wanted to go and put my arms around that little boy and hold him, and tell him not to cry.”

There were no Indians on the jury. There were two housewives, a railroad worker, a service-station operator, and Robinson, who is a teacher at the Beaverbrae School in Kenora. In their own way they tried to do their duty. After spending more than two hours deliberating, they produced a written verdict and recommendations that covered one, long, closely written page of the official form. The jury found that “the Indian education system causes tremendous emotional and adjustment problems.” They suggested that the school be staffed adequately so that the children could develop personal relationships with the staff, and that more effort be given to boarding children in private homes.

But the most poignant suggestion was the one that reflected their own bewilderment: “A study be made of the present Indian education and philosophy. Is it right?”

This originally was published in the February 1967 issue of Maclean’s magazine. Click here to view this article in the Maclean’s archive.