When it comes to parenting, can men really have it all?

We live in a culture where family is seen as an impediment to work, especially for men

Photo courtesy of Micah Toub.

Share

When my wife woke me up from a nap to tell me that she was pregnant, my first reaction was shock—after just trying for a month? My second response was joy—I was going to be a dad! Then came a sudden, mostly unexpected wave of disappointment and distress—my career, as I knew it, was over.

At the time, I was a freelance writer and my wife was a PhD student. We lived in a tiny apartment and had no car and few expenses. But now one of us had to get a job—the kind that pays every week. That meant that I had to put all of my grand, ambitious plans—some of which I’d actually started—on hold indefinitely.

I found full-time work and set aside my novel, a TV pilot and timely research for a non-fiction project that would quickly become irrelevant. The sacrifice I made is an age-old one: Forever, men have abandoned their poetry, bands and other preferred, lower-paying gigs to provide for their families. As I commuted to work each morning I felt proud of what I was doing, but the drive home was definitely dominated by frustration and despondency over everything I’d given up. The icing on the cake was the paltry amount of time that I actually spent with the 7 ½-pound reason I was doing all this. I was a father, but I wasn’t as much of a parent as I imagined.

It made me wonder: Will men ever be able to have it all?

That’s a bit of a joke, of course. The late Helen Gurley Brown, former editor of Cosmopolitan, set off decades of debate and backlash when she suggested in 1982 that women could “have it all” if they wanted. I’m fully aware that professional sacrifice has long been solely a woman’s burden to bear. And we all know that, even now that dual-income families have become the norm, women still take care of the majority of their children’s needs. But acknowledging all of this doesn’t remove the sting of trading in your dreams for having a family when it’s your turn.

READ: Inside the daddy wars

The fact is, all parents wish they could have it all. But all of us, in one way or another, must give up a part of ourselves for our kids. The sheer amount of time required to care for these helpless people reduces self-care and self-advancement to almost zilch.

But still, I refuse to give up. There must be a way to have at least some of it all, to balance things out for both men and women. So why does it seem like sometimes the world is dead set against that happening?

When it comes to balancing work and family, modern mothers must constantly push back against the expectation that their focus should be on home first. Fathers experience the flipside of that. Raising a kid with my wife, actively and equally, was always part of the plan, but there’s no question that my identity is more wrapped up in my career. While this isn’t true for all men, the fact is, on some level, it’s the way we’re primed to think about ourselves.

We all know the historical precedent of the near-absent father who arrives home from work after bedtime and misses school plays. But even now, as the more involved “new dad” is considered the ideal, he is still more judged at large by his professional status than his ability to soothe a crying child. That’s certainly one reason why, in 2015, only one in 10 Canadian stay-at-home parents was the dad. Sure, that’s better than the one in 50 dads from 1976, but it’s surprisingly low considering the increasing role of women as the breadwinners in their families.

When men decide to stay home, the reactions are often discouraging. One stay-at-home father of two, who now facilitates Toronto Dads Meetup, worked in New York’s financial sector four year ago when his first child was born. “My company had a two-week paternity policy, and not everybody took it,” says Amar. When he bumped that up to three weeks by adding vacation time, people made jokes when he got back. One colleague asked him, “Do you still work here?” For his second kid, he didn’t have to face the same grilling: When his wife’s prestigious, high-paying job relocated the family, he decided to stay home. Another dad I know took over from his wife for the 12th month of parental leave. When he returned to work, it was clear that others couldn’t truly get their heads around the idea of men as primary caregivers. “They asked me how my break was,” he remembers.

In my own case, when the birth of my son was a couple of months away, my wife insisted that I request the first three weeks off work. I agonized over that decision because I felt that anything over two weeks would be considered annoying to my new employer. They gave me no indication one way or another, of course, but that exact uncertainty proves the point that we live in a culture where family is seen as an impediment to work, especially for men. How could even the most well-meaning dads among us not internalize that?

Those who push back at the notion of a father sharing care in the early years often point out that men can’t breastfeed. True enough, but that’s a short-sighted approach if both partners want a balanced life. Setting routines together early on nurtures a father’s competence and confidence, creating a solid foundation for all the years to come. If he places firm boundaries around his work from day one, both parents’ careers get set on trajectories that, while diminished, are fair.

When you talk to people who study trends and policies related to families, they’re quick to bring up Quebec as a counterpoint to the rest of Canada. For one, the province provides a very attractive incentive for men: a paternity leave that can’t be transferred to mothers and pays fathers 70 percent of their salary for five weeks.

According to Nora Spinks, chief executive officer of The Vanier Institute of the Family in Ottawa, forced fatherly participation can have a powerful psychological effect. “When there is that kind of paternity leave, there’s a lot less pressure on dads personally because taking that time is expected and standard,” she says.

And indeed, whereas only 12 percent of men in the rest of Canada claimed parental benefits in 2015, 86 percent did in Quebec. Of course, new fathers in Ontario—where I live—can take all 35 weeks of parental leave if that’s what a couple decides. But then there’s the fact that, no matter who takes it, you’re only earning 55 percent of your salary (in Quebec, the first half of paternity leave pays 70 percent).

“There’s no reason why we can’t have a higher replacement income,” says Trish Hennessey, director of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives in Ontario. “It’s a sociocultural decision.” She explained that we, as a society, could collectively set a higher value on the work of a stay-at-home parent and, at the same time, also offer high-quality and affordable daycare, such as Quebec’s $7-per-day child care program.

Indeed, just as one’s parenting during a child’s first year sets the patterns for his understanding of the world, a society’s support of parents early on can have long-term effects. “Studies show that when fathers are actively involved in caring for a newborn, they become more engaged fathers throughout childhood,” says Spinks. “We also know that one factor that contributes to stress in a marriage and may lead to divorce is when one partner feels like he or she is carrying too much of the load, whether that is caring for a child or earning an income.”

One of the dads in Amar’s meetup group told me a hopeful story: He works for a tech firm in Toronto that tops up parental leave benefits to 70 percent for three months. On his last day of work before the birth, they sent him home with two weeks’ worth of frozen food and a box of diapers. When his son was eight months old and he requested to take an extended leave for 10 months to be the stay-at-home parent, they said his job would be waiting for him.

In my own family, we managed to strike a decent balance as well. When my son was 18 months old, I found a part-time job with an employer who never blinked when I bolted out the door at 4:30 p.m. sharp every day and never tried to get a hold of me on the two days I stayed home with my son. Once I realized the full extent of the primary caregiver role—by far, the hardest job I’ve ever done—I regretted not making time for it sooner.

While there are many moments of intimate, irreplaceable joy while taking care of your child solo, the notion of one person at home with a baby for five days a week for a year is an absolutely ludicrous idea. Mothers who do it know this, but somehow we go on letting this be the norm.

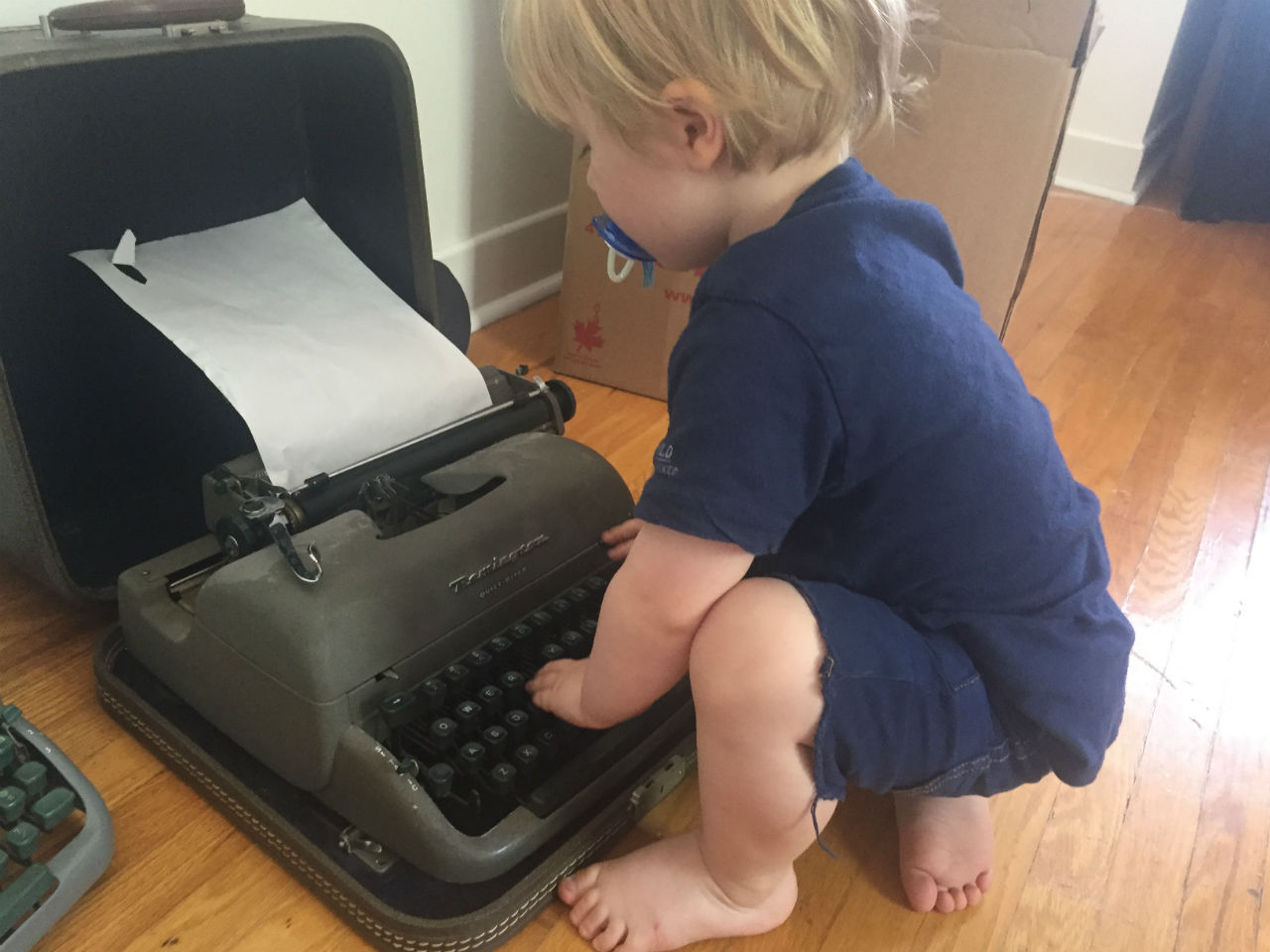

Now, at 3½ years old, my son definitely looks to me as equally as my wife for comfort and care. We alternate staying home with him when he is sick, and I organize as many weekend playdates as my wife does. With more time for my personal writing, I get some of my dream back, too. My lamentations over the loss of my bohemian lifestyle are subsequently fewer, but I still love when I find other dads with whom to gripe.

For instance, I was overjoyed when one fellow journalist told me he had to delay his book by a year and a half when his daughter was born. And I laughed when a musician friend told me that his son screams “No guitar, Daddy!” every time he starts composing. I felt so much less alone when I learned that, even though he can support his family with a part-time job, he still has to fight to make room for his personal work.

Having it all, it turns out, means giving up a lot. Or maybe that’s a glass-half-empty way of looking at it. In what became an unintended therapy session at the end of my chat with Spinks, she encouraged me to reframe how I conceive of these years of intense parenting. “It’s not about balancing work and family,” she says. “It’s about living life to the fullest.”

I can see that now. And I’m definitely going to get around to thinking more this way—when I have some time.

MORE ABOUT PARENTING:

- Adrian Crook: A fight on behalf of rational parents everywhere

- Why do so many women feel overwhelmed, stressed out and tired?

- The problem with the home-cooked, family dinner ideal

- Why using social media might make you a better parent

- Why my two children have different last names

- What happens when parents smoke pot

- Why parents should give up trying to produce perfect kids