Why Canadian babies have it so good, in seven charts

Seven charts that explain Canadian prosperity

Casey Lessard photo

Share

This article was originally published in 2015

It can be difficult to get beyond our ingrained pessimism and collective obsession with crises and disasters, but, as the new year gets under way, it seems appropriate to take stock and acknowledge that things, right here, right now, are pretty damn good. Infant mortality and smoking rates are down, cancer survival rates are up, and mass immunization programs have all but wiped out formerly common plagues and diseases. Compared to any point in human history, our food is better, cheaper and more plentiful. The drinking water is cleaner, and advances in sanitation make it possible for millions to live cheek-to-cheek. Crime rates are at historic lows, and Canada remains not only lawful, but blissfully peaceful, too, 200 years since it last suffered invasion.

Daunting challenges such as climate change still loom. But we are capable of confronting them. These seven charts illustrate all the advantages awaiting today’s Canadian newborns:

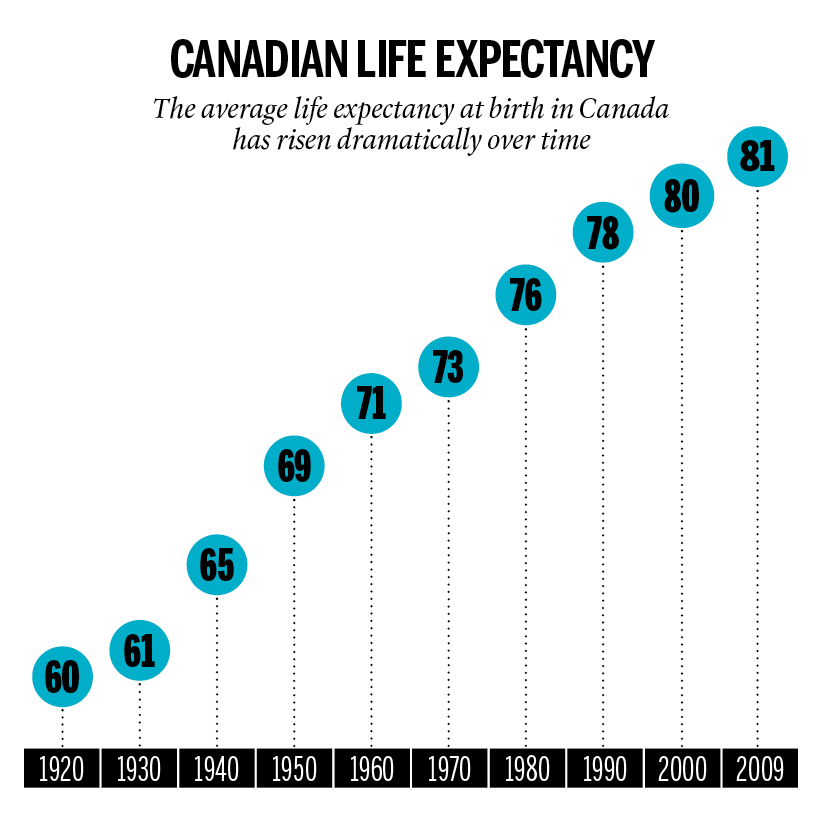

To live a long and healthy life has always been the heartfelt wish of parents for their newborn children. In 2015, such an aspiration is being fulfilled to an extent previous generations would have considered unimaginable.

No single statistic captures the health of a nation as succinctly as life expectancy at birth. A century ago, a typical newborn Canadian could expect to live fewer than 60 years. By 1950, the average lifespan had lengthened to 68 years. Another 10 years was added by 1990, and that progress continues unabated. According to Statistics Canada, a child born in Canada today can expect to see his 81st birthday. A female baby (women have historically lived longer than men) will likely live past her 84th birthday.

All this good fortune, it bears mentioning, comes despite repeated claims from many sources—public health officials, politicians, lobby groups—that children born today are fated to be the first in human history to live a shorter life than their parents because of rising obesity levels. While severe weight gain may precipitate certain health problems, overall life expectancy in Canada shows no sign of reversal, thanks to continual and offsetting improvements in health care, pharmaceuticals, technology and education. Plus, the gap between male and female lifespans has been shrinking in recent decades, reflecting an overall improvement in workplace safety and a decline in other causes of death for men.

By numerous other measures, the health of Canadians remains on a remarkable upward trajectory. Infant mortality has precipitously declined, even throughout the modern era: from 9.6 deaths per 1,000 population in 1981 to 4.8 currently. Survival rates for all cancers combined, the No. 1 killer of adult Canadians, are rising. Heart disease, the second leading cause of mortality, is in slow decline. Smoking is down. We’re taller. In 1972, nearly a quarter of adult Canadians were edentulous—or lacking any natural teeth. According to Statistics Canada, the toothless comprise a mere 6.4 per cent of our population today. And their new chompers are far better than the ill-fitting dentures of old.

The better health care and rising living standards that are responsible for a healthier and longer-living Canada are driving similar improvements in global lifespans, as well. Between 1990 and 2013, the world’s average lifespan lengthened from 65 years to 71.5 years, according to research published last month in the British medical journal The Lancet. This is largely due to reductions in infant mortality, malaria and diarrhea in Africa and Asia. Liberia, for example, added an astounding 20 years to the life expectancy of its citizens over this time. Experts have even begun talking about the possibility that First and Third World health indicators might some day converge.

With Japanese women—the world’s longevity champions—now living to be 87 years old, and with no sign in sight of any maximum human lifespan, Canadians today can look forward to many more decades of enduring improvements in life and good health.

—Peter Shawn Taylor

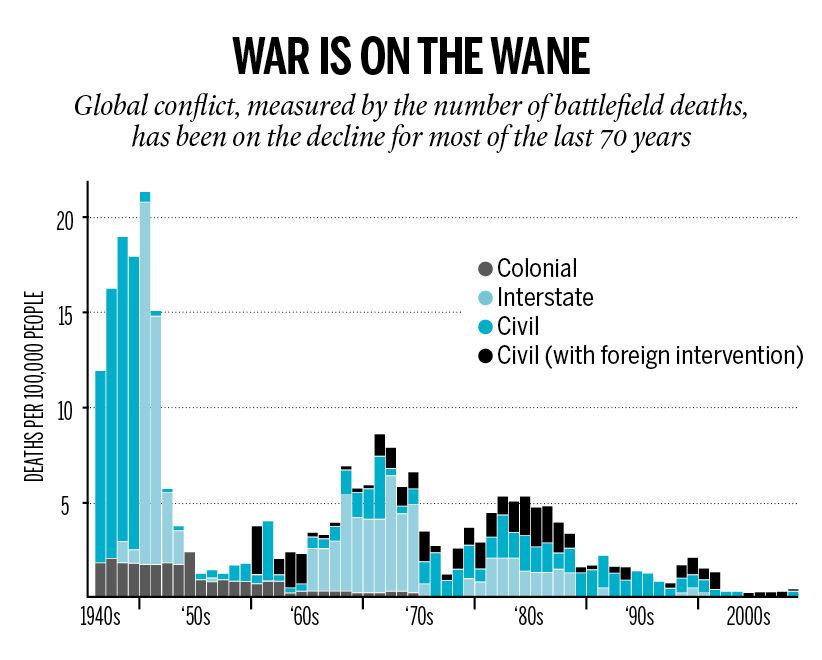

For as long as humans have walked the Earth, we have excelled at finding new ways to do harm to each other. But while war, terror and global strife dominate our 24/7 news cycle, the reality is that the world has not been this peaceful in a very, very long time.

In his 2011 book, The Better Angels of Our Nature, scientist and author Steven Pinker detailed how war has been on the wane for half a millennium. The annual number of interstate conflicts has fallen from an average of six in the 1950s to fewer than one last decade. Putting aside the conflict between Russia and Ukraine, Pinker’s observation that the 40 richest countries in the world have not gone to war against each other in nearly 70 years still stands. (This shows up in the dramatic decline in battle deaths, as shown in the accompanying chart.) Furthermore, the potential for catastrophic war has been lessened by the steady drop in the number of nuclear weapons lying about: By some estimates, the number of warheads stands at 18,000, down from 70,000 a quarter-century ago. Yes, that’s still uncomfortably high, but it’s been enough for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists to wind back the so-called Doomsday Clock—a measure of “how close we are to destroying our civilization”—from three minutes to midnight 30 years ago, to five minutes to midnight today.

It’s not just that global conflicts have becomeless deadly. So, too, have our streets. The world over, crime rates have fallen for decades, and Canada is no exception. Since peaking in the late 1970s, the Canadian homicide rate has dropped to its lowest level in close to half a century. Here’s one way to think about that: In 2013, there were 505 homicides, so, if Canada still had the same murder rate that it did in 1977, with our larger population, the total number slain would exceed 1,050. In other words, there are 547 people alive today—roughly the population of a 30-storey condo tower—who might otherwise not have survived 2013. Overall, the rates of all types of violent crime are in steady decline.

There are smaller, but no less important, victories to celebrate in the area of personal security. Canada’s roads are becoming safer: From 2000 to 2012, the annual death toll on roads in Canada, and 38 other nations contributing to the International Road Traffic and Accident Database, fell 40 per cent, a reduction of more than 45,000 deaths a year. And while there were several airplane disasters last year, 2014 had the lowest number of aircraft crashes since 1927—the same year Charles Lindbergh flew the Spirit of St. Louis across the Atlantic.

—Jason Kirby

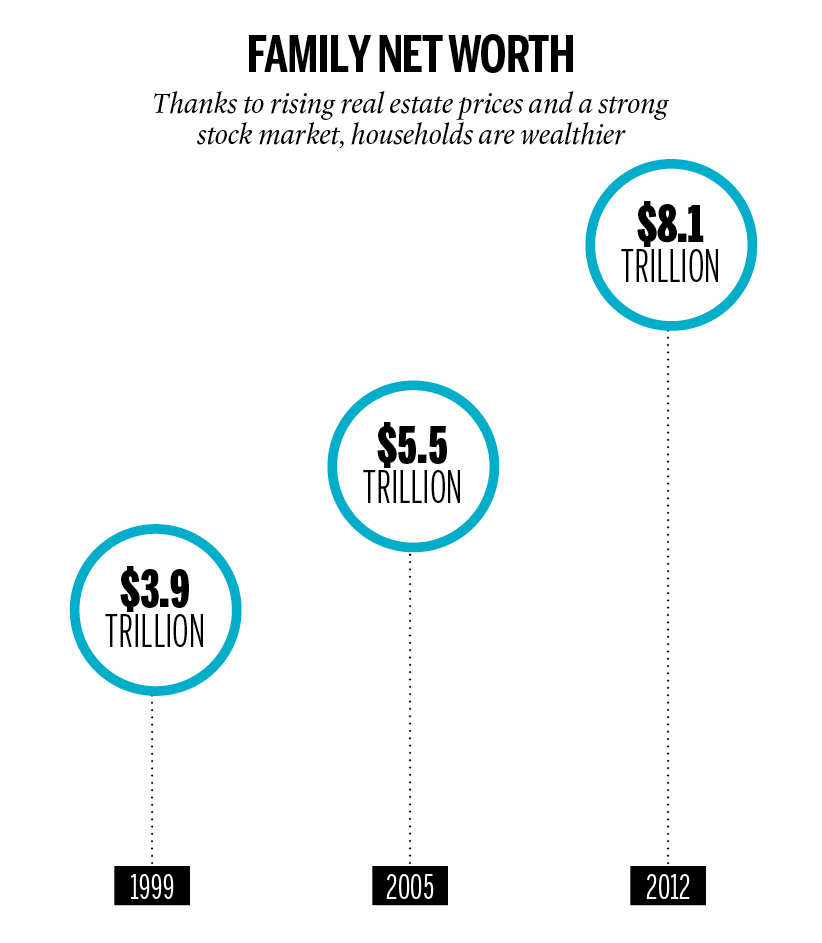

In the world of finance, there’s little time for long-term thinking. Stock prices are quoted by the second or even microsecond, traders eagerly await each monthly job report, while GDP marches ahead (or back) quarter by quarter. As useful as these metrics are for providing economic snapshots, they present a skewed picture of how the country is faring over time. So even while the news is full of ominous headlines about rising debt levels, falling oil prices or stagnant incomes, take half a step back and a completely different picture emerges—one in which Canadians have very little to complain about.

Add up all the assets owned by Canadian families—houses, stocks and even automobiles— then subtract their overall debt, and the resulting figure is their net worth. As of 2012, that number stood at $8.1 trillion, more than double what it was 13 years ago. That works out to a median family net worth of $244,000, compared to just $137,000 in 1999. While poverty remains a problem in Canada, with Statistics Canada’s new measure suggesting there are still 4.7 million low income households (the figure isn’t comparable to existing data), the government’s previous methodology suggested the percentage of Canadian households defined as low-income had dropped to 8.8 per cent by 2011, compared to 15 per cent in the late 1990s. We can also take comfort in knowing Canada’s poorest citizens are still better off than the vast majority of the world’s population. According to the Conference Board of Canada, the average income of the bottom 20 per cent of families is $14,500 a year, more than what three-quarters of the world’s population lives on. The comparison comes even as the number of people living in extreme poverty around the world—defined as living on less than $1.25 a day—has fallen to two out of every 10 people, compared to nearly half in 1990.

In Canada, rising wealth has made day-today living far easier. A record number—nearly 70 per cent—own their own homes, while the share of household budgets being consumed by the purchase of food and groceries has plummeted to about 14 per cent, the lowest level ever—thanks in part to growing constellation of retail options ranging from farmers’ markets to Wal-Mart supercentres as well as more efficient food manufacturing and agricultural sectors. That, in turn, frees up more money for children to play hockey or study the arts. And only about five per cent of Canada’s seniors now live in poverty compared to a staggering 30 per cent in the mid-1970s. Better yet, the average retirement age is now 62, down from 65 in the mid 1970s. In the post-Second World War years, that was roughly the life expectancy of Canadian men. The good old days? Hardly. We’re living them right now.

—Chris Sorensen

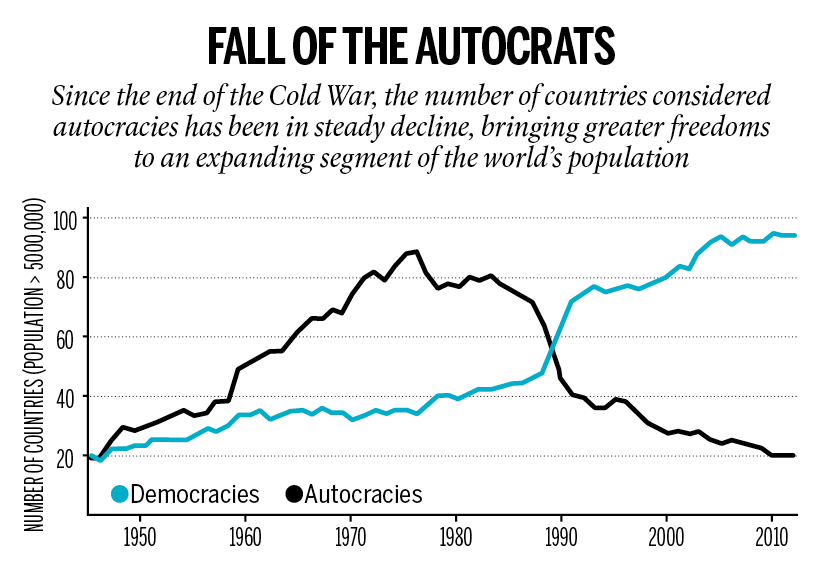

Democracy, it’s said, is the worst form of government—except for all the others. Fortunately for the world, democracy has been on the march for decades and has the potential to flourish even more.

As the accompanying chart, from the Center for Systemic Peace, shows, the global trend since the end of the Cold War has been a rise in the number of countries classified as democracies. The free world should never be self-satisfied, of course. Freedom House, in its most recent annual report analyzing the ebb and flow of political rights and civil liberties, warned that in 2013 more countries (54) registered declines in freedom than those that made gains (40). But it also contained an important statistic—40 per cent of the world’s population now lives in free countries, while another 26 per cent reside in countries that Freedom House deems “partly free,” like Mali and Ukraine. This is remarkable, given the millennia of human history when individual liberty was nonexistent. As for the balance of the world’s population living in “not free” countries, half reside in China. But the wonderful thing about democracy is, it’s contagious. The challenge now is running up the score.

On various counts, we in Canada can pride ourselves as a leading star of the democratic world. In terms of female representation at the national level, Canada exceeds the global average—with 77 federal seats out of 308 currently filled by women. For a brief moment in 2013, six premiers were female while Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne is the first lesbian to lead a Commonwealth government. The Charter of Rights and Freedoms has become a leading example of constitutional law, while Transparency International’s corruption perception index ranks Canada in the top 10 for perceived cleanliness out of 175 nations. In two years, we will celebrate 150 years of unbroken democracy (presuming things don’t go terribly wrong between now and then).

But again, democracy does not reward complacency, and we have much to be concerned with: declining voter turnout, an ineffective national legislature, a degraded discourse. The good news is Parliament’s sorry state is being widely noted. If admitting we have a problem is the first step, we should hope to figure out the second step soon.

We might remind ourselves that we already have what those students in Hong Kong demanded last fall: an open democracy with basic freedoms and rights. Courtesy of our ancestors, we have the stability and institutional infrastructure that billions envy. Reform is necessary, but reformers operate from a position of great advantage. As the world moves to the side of democracy, Canada is well-positioned to help lead.

—Aaron Wherry

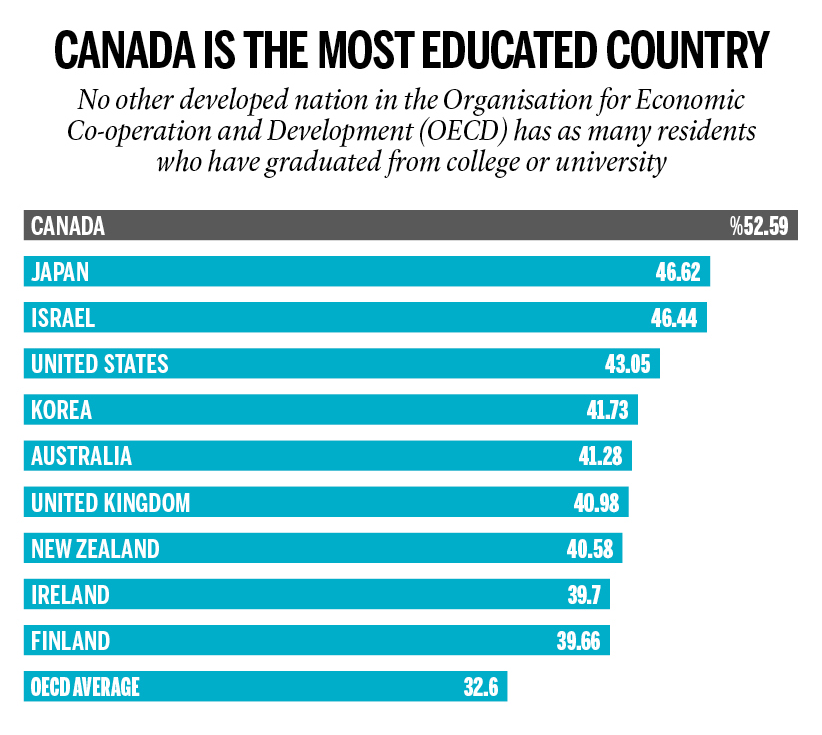

They can’t all be baby geniuses, but, across the world, parents keen on seeing their children get a solid education could hardly ask for better odds. Not only are more children going to school than ever before, they are staying in school longer. According to UN figures, rates for primary education in developing regions jumped from 83 per cent in 2000 to 90 per cent in 2012. Enrolment rates among girls, in particular, are on the rise. (Thank you, Malala.) Youth literacy has also improved among 15- to 24-year-olds globally, to 89 per cent in 2012, up from 83 per cent in 1990.

Canada, of course, is among the best-educated countries on the planet. The share of the adult population with only a high school diploma is shrinking fast, and is less than half the average seen in other developed nations. In fact, the number of full-time university students more than doubled between 1980 and 2010. Canada is the only developed country where more than half the adult population graduated from college or university. And helping to offset schooling costs is a 10-fold increase in scholarship and bursary dollars, which have risen to more than $1.6 billion today, from $150 million in 1990.

At the same time, while we hear a lot about the rising student debt burden, the fact is that grads are in a better position to juggle their loans than they have been in more than 20 years. Interest rates are way down from the double-digit levels of the 1990s. So, too, are taxes, which, in the early ’90s, also took up 28 per cent of the average income for a graduate two years out of school. Today, that number is 22 per cent. The annual average income for a graduate two years out, meanwhile, has remained relatively stable during that span, around $46,000. Take all this into account, and the average grad’s debt burden is actually a third lower today than it was at the turn of the century.

Looking for a smart investment? Maybe try the cap-and-gown rental industry.

—Aaron Hutchins

Canada’s reputation for being green has taken a hit in recent years, thanks to growing global concern over climate change and the development of CO2-intensive resources such as Alberta’s oil sands. But while the controversy points to difficult choices ahead, it has overshadowed impressive gains in environmental protection elsewhere that make the air easier to breathe, water safer to drink and wilderness more pristine. On all these fronts, the trends are getting better.

Over the past 40 years, the amount of particulate matter suspended in the air has declined by 50 per cent in Canada, helping to reduce smog and a host of related health conditions, including asthma and emphysema. Concentrations of lead have declined by almost 96 per cent, as have concentrations of sulfur dioxide—a key precursor to the phenomenon of “acid rain,” which kills lakes and corrodes buildings and monuments.

Canada has also been a world leader in monitoring the Earth’s protective ozone layer, which shields the Earth from harmful ultraviolet radiation. Overall global consumption of ozone-depleting substances, including chlorofluorocarbons, has decreased by 98 per cent since the mid-1980s, according to UN data. Other global green success stories include the 14 per cent of territorial and coastal marine areas that are now under protection. Meanwhile, in the past two decades, more than two billion people have gained improved access to clean drinking water and better sanitation.

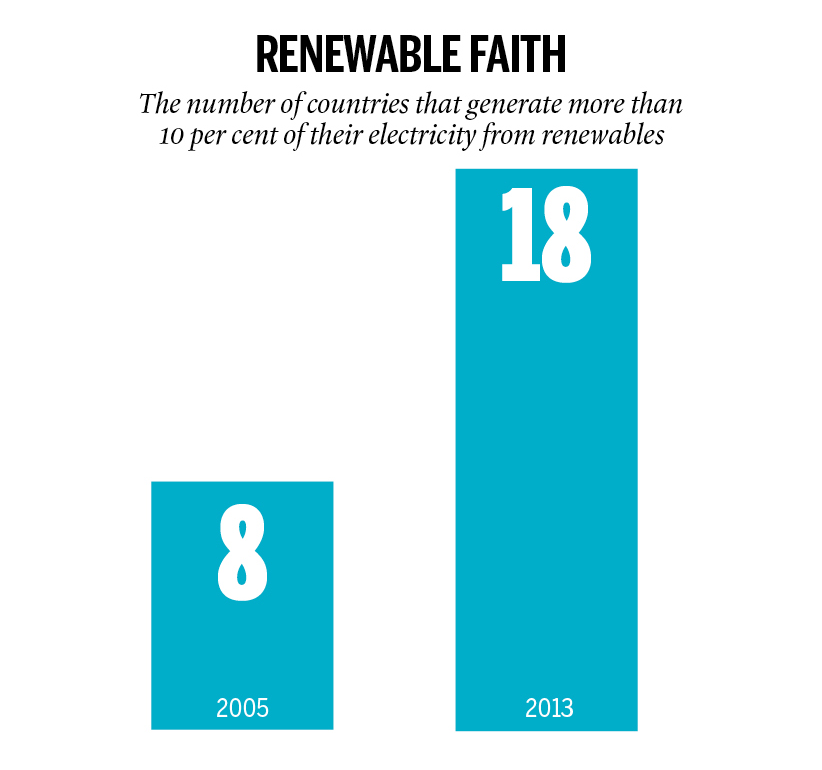

As for climate change, there’s reason for optimism. As of 2013, at least 18 nations generated more than 10 per cent of electricity from renewables such as wind and solar, up from just eight per cent three years earlier.

—Chris Sorensen

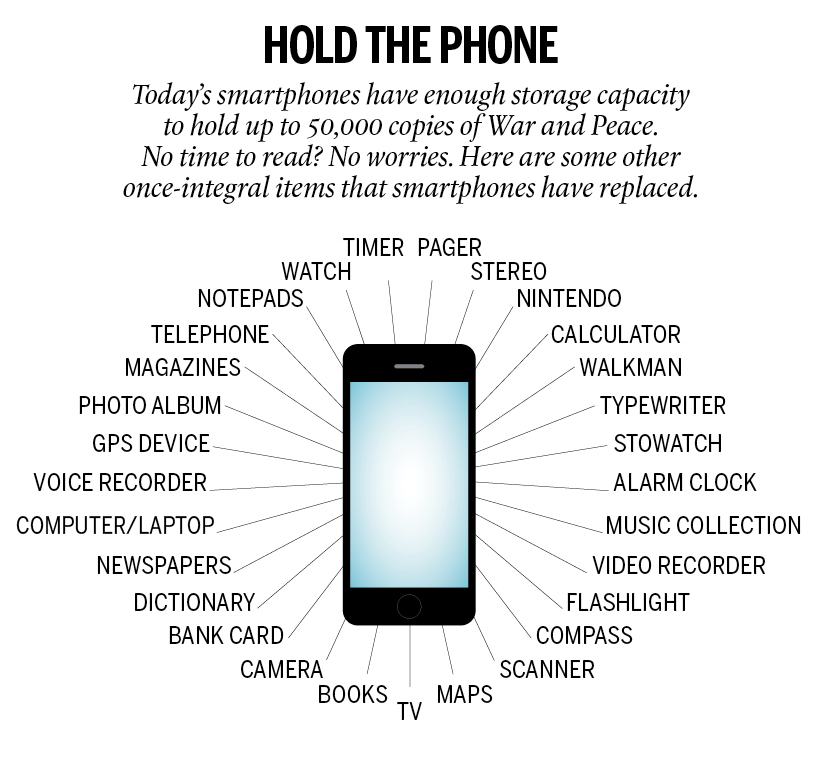

There are many once-common headaches newborns today will never understand, like stopping a car on the side of the road to pull out a map, or that time you picked up the home phone and ruined the dial-up Internet connection. As much as some may complain about modern technology consuming our lives, carrying a smartphone sure beats having to lug around a boombox for portable music or visit the library constantly for research. Not to mention having to dial someone up at home on a rotary phone.

There are nearly as many mobile phone subscriptions (6.9 billion) as people on Earth. In terms of getting online, more than three billion people—40 per cent of the world’s population—will be using the Internet this year. Developing regions have seen increased connectivity too, where the number of Internet users has doubled over the past five years.

It’s not just a tiny screen enriching our understanding of the world, either. We travel more than ever before. (Global air passenger transport grew by 76 per cent between 2002 and 2012, up to 2.8 billion travellers.) Our countries are becoming more culturally diverse too. Xenophobia be damned. Roughly 230 million people live in countries where they weren’t born, compared to 154 million in 1990. At the same time, Canada’s visible minority population grew almost fourfold from 1981 and 2011, to 6.3 million, roughly 21 per cent of our population and the highest proportion among G8 countries. This has brought a rich diversity of food, fashion and art most could only imagine 20 years ago.Need proof? Check online.

—Aaron Hutchins