Why romance novelists are the rock stars of the literary world

Romance writing isn’t just a billion-dollar industry. It’s also the nicest meritocracy around.

Share

When American filmmaker Laurie Kahn set out to make Love Between the Covers, a documentary about the women who read and write romance novels, she was struck by how often she heard the same story. It wasn’t a tale of beefy bodice rippers or love at first sight; it was a story about snobs. “I can’t tell you how many people I interviewed,” says Kahn, “who told me that people will walk up to them on a beach and say, ‘Why do you read that trash?’ ” Apparently, where lovers of romance novels go, contempt follows. Sometimes it’s subtle contempt—a raised eyebrow from a colleague, or a snarky comment from a friend (usually the kind of person who claims to read Harper’s on a beach vacation). Other times it’s more overt, even potentially damaging. When Mary Bly (pen name Eloisa James), an academic and New York Times bestselling author, began writing romance, she was advised to keep her fiction writing secret or risk not making tenure at the university where she worked.

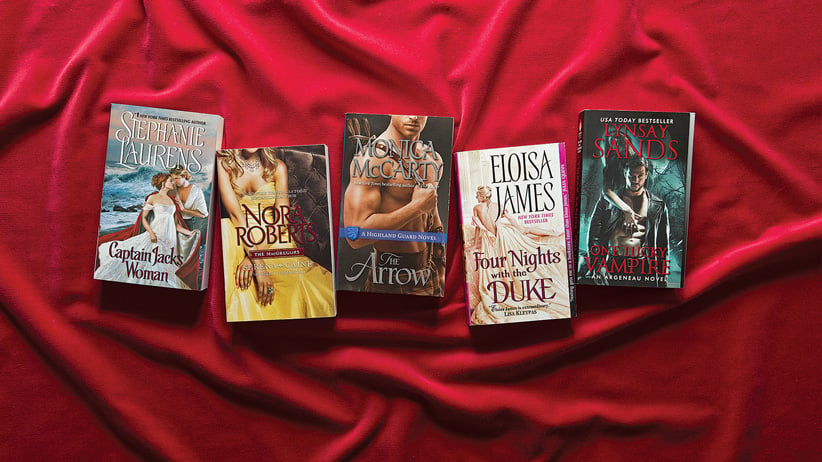

For some reason, argues Kahn, perhaps because its subjects are female, romance novels are perceived as fundamentally silly, when other popular “genre fiction”—namely, fiction by and for men—is not. “Nobody,” she says, would walk up to “a man reading Stephen King, or a mystery or sci-fi novel” and scoff. And she’s right: Stephen King may write circles around romance novelist Nora Roberts, but mystery-thriller buffs James Patterson and Dean Koontz most certainly do not. Yet Roberts is the butt of jokes—a universal default example of “bad writing,” while her equally schlocky male contemporaries get a free pass.

A filmmaker whose previous work includes the Emmy-winning documentary A Midwife’s Tale, and Tupperware!, a film about American women of the 1950s who made small fortunes throwing Tupperware parties, Kahn wanted to explore not only the double standard faced by romance authors, but the wild success and collaborative nature of the romance community itself. Love Between the Covers, which premieres at Toronto’s Hot Docs festival at the end of the month, explores life from the perspective of the genre’s giants and veterans—the Nora Robertses and Beverly Jenkinses of the field (the latter a pioneer of African-American romance writing)—and its millions of readers and aspiring writers, some of whom work full-time jobs, yet write more than a thousand words every evening. (When Lenora Barot, pen name Radclyffe, began writing what would become groundbreaking lesbian romance fiction in the ’90s, she was a full-time plastic surgeon.) “It’s these untold stories of women that really appeal to me,” says Kahn. “Here is this community that is huge. It’s a multi-billion-dollar business and the women in it are writing a huge range of romantic fiction and no one gives them the time of day.”

The amazing thing is that this historically derided genre is not only wildly successful (it regularly outsells both mystery and sci-fi; Romance Writers of America estimates the genre made $1.08 billion in sales in 2013) but also preternaturally friendly.

In an age where women are constantly encouraged to “lean in” at predominantly male workspaces, there exists this frequently ignored, yet massive and diverse, woman-steered industry where writers literally tutor their competition. As Bly says early on in Kahn’s film, the romance industry may be one of the last meritocracies left on the planet.

And it’s a very functional one. The annual Romance Writers of America conference, where thousands of authors offer detailed advice to newbie writers on everything from where to pitch to how to find an agent, is unique in a publishing world in which authors are typically discouraged from discussing their contracts openly. Kahn attributes this friendly, inclusive atmosphere, in part, to the recent popularity and acceptance of self-publishing (formerly known as “vanity publishing”).

A common criticism expressed about major romance publisher Harlequin (which declined to comment for this story) is that it promotes the “line”—the type of romance novel, be it “historical” or “intrigue” or other—over the author. Apparently this has been an issue for a long time. “Because of this practice, romance authors have to hustle their own books and find their own markets,”writes Leslie W. Rabine in her 1985 essay, “Romance in the Age of Electronics: Harlequin Enterprises.” They can also have a difficult time getting royalties from publishers, they report, with waits of up to two years, Rabine adds. Today, many romance authors have turned that liability into a strength. If they’re going to do the hustle on their own, many writers figure, why not reap the bulk of the financial reward? Ironically, the entity that’s allowed them to do this is the biggest publishing behemoth of them all—Amazon. Kahn says that, in the three to four years in which she worked on the film, “There’s been a revolution in publishing, and it has upended everything. It used to be that the power was completely in the hands of the publishers, and authors were like hitchhikers waiting by the side of the road, hoping some agent would pick them up,” Kahn says. “When I was shooting, Amazon started Kindle Direct Publishing. That radically changed the picture.”

Shelley Bates (pen names include Shelley Adina and Adina Senft), who writes steampunk and Amish romance fiction, was once one of those metaphorical hitchhikers waiting for an agent to pick up her new book series, Magnificent Devices, set, according to her website, “in an [alternative] Victorian age where steam-powered devices are capable of sending the adventurous to another city, another continent, or even another world.” Bates grew up on Vancouver Island, and today lives near San Francisco with her husband, where, in addition to writing fiction, she rescues chickens (some of them abandoned, others coming to her from people moving out of the area who “can’t take their birds with them”). She shopped her series around to 10 different publishers in 2010, all of which rejected her. She says the editorial department at a major U.K. publisher was really interested at one point, but eventually turned Magnificent Devices down because it wasn’t sure how to market steampunk.

“I put it out myself [on Amazon] in 2011,” says Bates, “and, eight books later, it’s going up like gangbusters. That’s what paid for the house.” Bates, who hired a graphic designer for the cover and marketed the book herself, says she made “six figures” in 2013, and again in 2014, success she attributes to self-publishing and the collaborative nature of her business model. “Suddenly I realized I could go directly to my readers. I bounced things off them on my blog,” she says. “It’s not writing by committee, but my readers are so invested. I’ll give them two cover options [for a book] and they’ll come back and tell me and that will be the cover.”

Romance writers may get little respect from the literary world, but they are, without a doubt, its rock stars. “We don’t really care what the establishment thinks, because we’re paying off our houses,” says Bates. “Readers vote with their wallets. I think the big-publisher business models will have to become more author-friendly if they want to retain their authors.”

Or perhaps they’ll have to embrace diversity. The notion that steampunk, for example, wouldn’t sell, or would be too difficult to market, is a sensibility at odds with other forms of popular entertainment—from television to Hollywood movies—where many producers have realized that diverse ideas and new voices do well in the mainstream. Because publishers sell books to retailers, as opposed to readers themselves, they have an often confused perception of what readers want and who reads what. This is a frustration Barot, who also publishes LGBT books, knows well. She says she’s seen some of her own books placed in the “cultural studies” section of major bookstores—the likely assumption on the part of retailers being that LGBT romance is too niche for general fiction. In other words, if you’re a run-of-the-mill heterosexual romance novel, you’re the subject of cheap ridicule, and if you’re an LGBT romance novel, you’re perceived as irrelevant outside the realm of esoteric academic study.

In the end, the most common assumption about romance novels, buoyed by the success of Fifty Shades of Grey, is that they are anti-feminist. And though the so-called bodice rippers of the 1970s (in which men who look like Fabio ravish passive sweethearts) are still quite popular, the genre has also expanded rapidly in recent years to include fiction of the paranormal, gay, evangelical, steampunk, time travel and Gothic variety (and many more). Its female leads, in many contexts, have evolved with the times, rendering the notion that romance novels are full of oppressed, unthinking women, profoundly ignorant. Not only is the industry itself rife with female entrepreneurs; its heroines always get what they want. In fact, the only formula that rings true across all romance novels is the HEA: the Happily Ever After. It is unanimously believed to be the defining principle of the genre. “The women always win,” says Kahn. “And that doesn’t happen in most places.”