The world needs a digital Geneva Convention to fight cyber attacks

Scott Gilmore: The damage from cyberattacks is real, and the threat risks escalating into lethal conflicts

Share

Imagine a medieval knight charging across the battlefield on his warhorse, visor down, lance lowered. He was the M1 tank of his time, and just as costly. In order to afford the horses (there had to be several spares), the squires, food to feed them all, his weapons and of course his shining armour, a knight required an estate with up to 500 serfs working the soil. And, like a modern tank, he was critically important in any campaign. Clad in over 100 lb. of steel and riding a destrier that weighed more than a ton, the knight was an unstoppable force that could break the strongest line of defence.

Then, in the 11th century, a few small technical changes were made to the crossbow. These added a little more power to the bolt, just enough to pierce plate armour. Suddenly, our charging knight is crashing into the mud with a bolt through the chest, fired by a serf standing 300 yards away.

Not long after, in 1096, Pope Urban II issued a papal decree banning the crossbow. The pope was not motivated out of particular concern for the horrifying wound a bolt could make, but because it threatened to dramatically destabilize the balance of power. If untrained peasants, armed with cheap crossbows, could kill a knight, then suddenly the wealthiest kingdoms were vulnerable to threats from the poorest, which made conflict far more likely.

This fear of the instability created by a new technology is what has motivated most of the arms control conventions in history. For example, in 1675, the Strasbourg Agreement prohibited poison-tipped bullets. After the First World War, the Geneva Protocol banned biological and chemical weapons. In 1967, the Outer Space Treaty forbade placing atomic bombs in orbit. Today, we face a new technology, one that is dramatically destabilizing the world: cyberattacks. It may be time for a digital disarmament treaty.

RELATED: Goal of latest mass cyberattack possibly not financial, say experts

In 1970, a computer technician named John Draper committed one of the first cyberattacks when he used a plastic whistle that came in a Captain Crunch cereal box to mimic the tone that opened up a trunk line on payphones, giving himself 75 cents worth of free long-distance calls. And last year, cyberattacks like the one that recently compromised the credit reporting firm Equifax caused trillions of dollars in damage to the global economy. The size, frequency and impact of these attacks are increasing at an exponential rate.

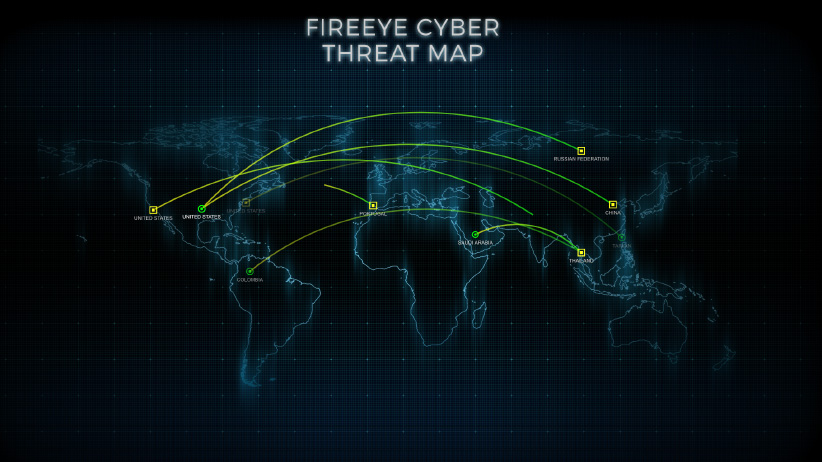

But the most troubling part of cybercrime is how it has been enthusiastically embraced by states. Countries that cannot project power by conventional means, such as Russia, North Korea and Venezuela, are waging a digital war, and they are causing real damage. For example, in December 2015, the Russian government attacked the Ukrainian electricity grid—not with rockets, but with phishing emails and viruses. But the impact was the same: a quarter of a million people were left without power. In fact, in some cases, the damage caused by a digital attack far surpasses that done by conventional weapons. Consider the Russian destabilization of the American political system.

The potential damage of cyberwarfare is growing as more states create their own capabilities, and as the global economy becomes more digitized. Some experts are warning that the growth of the “internet of things,” which connects even small household appliances to the internet, is creating massive new vulnerabilities to domestic infrastructure, the equivalent of allowing the Russians to park an artillery brigade on the outskirts of Denver.

What is more worrying, though, is the risk that these digital attacks will boil over into conventional or even nuclear war. How would Washington respond to a North Korean virus that shut down infrastructure in the United States? Or an Iranian attack on their air traffic control systems? We don’t know. And that’s the risk. Belligerents are launching assaults without understanding what it may provoke.

READ MORE: How MacEwan University got duped out of $11.8 million by scammers

There have already been some diplomatic efforts to control cyberattacks. Twenty-five of the United Nations’ 193 member states convene on a regular basis to flesh out some basic principles of détente. But these are both non-binding and somewhat vague. There have also been some bilateral agreements, such as a recent accord between Beijing and Washington to stop the cybertheft of intellectual property.

In spite of these nascent efforts, the threat of cyberattacks continues to grow. Which is why Microsoft made a bold proposal earlier this year to establish a digital Geneva Convention. The original treaty set binding requirements on the treatment of prisoners of war and non-combatants. What Microsoft is proposing would completely ban nations from conducting cyberattacks and establish a neutral international body that would investigate and attribute attacks that do occur.

So far, there has been no serious reaction from governments, including Canada. Nonetheless, the need is obvious. Right now, nation states feel free to attack anything—power grids, credit card companies, payroll systems—without much fear of reprisal. The damage is real, and the threat is creating new uncertainties and risks escalating into lethal conflicts. Pope Urban II feared this type of instability, and we should too.

MORE ON CYBERSECURITY: