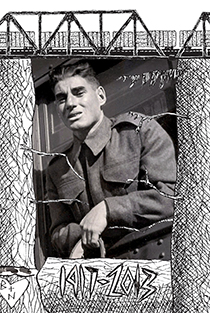

William Bell

From a POW camp in Japan, he saw the flash of Hiroshima; it was the light that would save him and maim him all at once

Illustration by Team Macho

Share

William Bell was born in Winnipeg on March 12, 1917, to Scottish parents: his father, Bill, a butcher, and Rachel, a homemaker. With his full lips, dark, quiet eyes and a great crop of the thickest black hair, he was an active boy, diving from railroad bridges into the Red River with the Riverside Boys Swim Club, and learning to box. The Depression forced him from school, and at 16 he hopped a rail car for work in B.C., felling trees by handsaw. When the Second World War broke he returned to Winnipeg and, along with his brother Gordon and many of his swim-club friends, enlisted in the Winnipeg Grenadiers. He was 22, Gordon just 19. “Bring back your brother,” Bill’s mother told him.

While stationed in Jamaica, Bill guarded a camp of German POWs, unglamorous work. Otherwise, his memories of that time came to revolve around food, the mark of a mind defined by the privations he’d soon encounter—a Dutch submarine laden with cheese and canned fish, the coffee and nights of beer—and Jamaica remained for him always a kingdom of rum-laced ice cream. Things changed in late 1941, when the Grenadiers left the West Indies for the lush hills of Hong Kong, arriving to the sound of bagpipes. Within weeks, they’d be plunged into brutal combat. On one mission, Bill stumbled upon a nest of Japanese machine guns. His comrade, shot in the neck, died instantly; Bill took a bullet to the hip. Days later, he helped fight the enemy off from a hollow, a dazzling flurry of swords raised above him. He shot one charging officer in the stomach and, with a burst from his Tommy gun, lifted a second in the air before he could savage Bill’s friend with his bayonet. Confronted with hurled grenades rolling underfoot, the Canadians tossed them back. When one landed beyond reach, Sgt.-Maj. John Osborn threw himself on it, sacrificing himself to save his fellows. “It was the bravest thing we had ever seen,” Bill later wrote in a short memoir.

After 17 days fending off the more numerous Japanese, some 290 Canadians died, many of them Bill’s best friends. “Where’s the rest of you?” one enemy officer asked when they surrendered, so shocked was he at how few had killed so many. They’d spend the rest of the war as POWs—“a new living hell,” in Bill’s words. At a camp in Hong Kong, young Gordon nursed a wounded Bill to health; the Japanese separated them when they found out they were brothers. Bill survived on meagre rations of rice laced through with maggots and rat droppings. When a Chinese refugee came begging, they watched as a guard beheaded him. Later, in a series of camps near Tokyo, they were made to work, ferociously, labour that put Bill back to cutting firewood. That blend of hunger, toil and illness—dysentery, beriberi, malaria—was often lethal. Bill’s chores included cremating the dead with a Buddhist priest, who chanted as the bodies burned.

One morning, they saw a flash of light blossom on the horizon. The next day, they awoke to find their guards gone; they did not know the guards had orders to kill them. “If it weren’t for the use of the atomic bomb, as horrible as it was, I would not have survived,” Bill wrote of Hiroshima. Short of food, they bartered for a horse, and with nothing but a blunt knife, slaughtered and dismembered the animal, stewing it in a great vat. The sight of the hooves shod in their horseshoes, dancing in the soup, remained an indelible memory for Bill, who had spent 42 months in captivity. Only later did he learn Gordon had died, seeing in it a promise to his mother broken.

Back in Winnipeg, Bill wed Nada, a pretty farm girl, and had two sons, Bill and Dennis. He looked fit, but like the rest of the Hong Kong vets, he was a damaged man. “He was like a caged animal—a tiger in the zoo,” says his son Bill. Shrapnel fell from his skull when he combed his hair. Doctors said he’d not live past 50. He found comfort only in his wartime comrades, with whom he drank, sometimes all night. Later, he tamed himself, and quit drinking. A quiet man who smiled with his eyes, he rarely spoke of the war, and never ill of the Japanese. He waited until his 80s to tell his sons his story. Otherwise he hummed, and taught his granddaughters to cartwheel. His bouts of skin cancer he attributed to radiation from the Hiroshima blast, that strange light that saved him and maimed him all at once. Dozens of operations pared him down—a slice of face, a pruned ear. “His back was like a roadmap,” says Bill. In hospital at the end, he muttered in Japanese. On his 96th birthday, he came to in a hospital bed, a startled expression in his eyes. “Go to the light, if you see the light,” Nada, his wife and most constant nurse, told him. And he did.