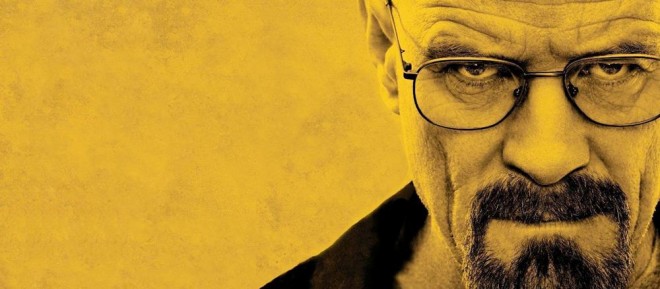

Breaking Bad and the villainous anti-hero

A few thoughts on last night’s fourth season finale (spoiler alert!)

Share

A few thoughts (spoilers undoubtedly included) on last night’s fourth season finale of Breaking Bad:

A few thoughts (spoilers undoubtedly included) on last night’s fourth season finale of Breaking Bad:

It’s a bit funny, though harmless to the future of Breaking Bad, that what creator Vince Gilligan says he intended as a pretty un-ambiguous season 4 ending shot was not always interpreted that way. Just as with last season’s finale, some viewers took to arguing over the meaning of the ending, or the possibility that something else really happened. It’s sort of a reminder of why television traditionally would hit us over the head with everything that happened (and still does, on many shows), providing a verbal explanation for every plot point. When a show provides a mostly visual plot point – I was about to say purely visual, but actually this last shot was heavily built up to in Jesse’s dialogue – it seems like it will always be a point of controversy until dialogue confirms that it happened. Next season, someone will confirm in dialogue that Walt is the poisoner, and no one will be arguing any more. Maybe it’s that TV is still subconsciously considered kind of a verbal medium; it’s hard to convince every viewer that something occurred until someone says it.

Breaking Bad gets a little wilder every season, and that’s a compliment; the explosion scene, which Gilligan himself compared to a cartoon, shows just how much the show benefits from the sense that anything can happen. When Gus walks out of the room after the explosion, for one moment, you think that he somehow survived. Logically, you know they wouldn’t go that crazy, but you don’t know for sure that they wouldn’t, so for a split second it seems like he might be okay. Whereas if it happened on any other show, you would either know that they’d never stretch that far, or, more likely, the writers would never even try to get away with what did happen in that scene – it would be silly on any other show. (Most shows could not feature a man remaining cool, calm and stone-faced after half of his body has been blown off; we wouldn’t believe in anything that happened after that. After four years of Breaking Bad, the cartoon explosion, Walt’s complicated plan and Gus’s death are all just within the bounds of reality.) I think it doesn’t necessarily follow that the fifth and final season will continue this pattern. Now that the writers are free from the need to keep Walt alive indefinitely, and now that they’ve retired the supervillain character of Gus, they do have the option to go smaller. (Arguably they already started going smaller this season, by focusing some of the episodes on seemingly more mundane stories. But you could sort of see that this was going to end with Gus or Walt dead, and it couldn’t be Walt.) I’m not saying they will, but one thing to look forward to about the final season is that having wrapped up so much of the last two and a half seasons’ storytelling, Gilligan has a lot of options open to him, and I’m not sure where he’ll go.

One thing that is obviously likely to continue, no matter what the stories of season 5 turn out to be, is the main theme of the show: taking a typical TV anti-hero and turning him into a full-out villain. It says something about how ingrained the concept of the anti-hero is in TV today—cable TV at least—that making a character’s bad behaviour less morally ambiguous is a subversion of what we expect. And a lot of arguments over Walt White do revolve around whether he is still an anti-hero we can identify with, or when he crossed the line into just being horrible. (Also, another TV convention these last couple of episodes have used in a way is that the absolute worst thing a character can do is hurt a child. Walt can kill or indirectly kill or harm as many adults as he wants and still be something like a regular anti-hero. Harming a child, in the moral grammar of TV, may be just about the only thing that can prove a character is irredeemable.)

The show has also been playing around with levels of villainy. When the season began, Walt was a bad guy suffering from the delusion that he was a supervillain, fully in control of his own destiny. Of course he was no match for the real supervillain, Gus, because he just hadn’t quite gone far enough. In the finale, he was able to devote himself single-mindedly to the goal of killing somebody and removing even the tiniest question about whether there is something he would not do. When he says coldly that he “won,” he’s sort of graduated to being a better, tougher bad guy. The older bad guys already seem to know that what matters most is whether you win, like the man who is willing to blow himself up just to score points over his adversary. You graduate when you stop worrying about why you’re doing this, except that you’re winning.

Which, from the character’s point of view, is probably a sensible decision, since being good at villainy is really all he has left. One of the reasons the character resonates beyond the world of crime fiction is that he’s a recognizable type, the kind of person who has almost nothing positive left to define him. The show first hinted, and then confirmed, that he’s replaceable as a creator of drugs – as a creative person, then, his contribution has pretty much been made, and nothing remains except to repeat himself endlessly or stand by while others repeat it. So fulfilment in creativity is not the answer. He can’t fulfil himself by spending money and having fun, because the money he’s making has to be spent carefully to avoid detection, even by some of the dumbest cops in the world. And he certainly can’t find fulfilment in family life, because he’s on cable. So any sense of self-worth he has will have to come from the mere fact that he’s winning, that he’s in control, that his plans work. It’s a bit separate, as the show currently stands, from the idea that people become so wrapped up in the mechanics of crime that they lose sight of their goals. Given that the show is about a man who turns to crime to gain control of his life and destiny, the character is arguably fulfilling his goal just fine.

This may be one of the things that separates the modern anti-hero/villain from the ’70s film anti-heroes who inspired them (the Sopranos era of TV drama was to TV as the New Hollywood was to film). Those anti-heroes usually had some kind of broader purpose, like running a business that would work better than the government (The Godfather) or cleaning up a sick city (Taxi Driver) or just having a good time. The Walt White kind of anti-hero is engaged in a narrower search for self-definition and order; that’s one of the reasons he’s supposed to read more as a villain than an anti-hero, that his motivations, while understandable, are basically just narcissistic.