Opening Weekend: ‘Score’ and ‘Carlos’

A choice of icons—the singing, skating pacifist or the bomb-crazy Marxist Marlboro man

Noah Reid (centre), the star of ‘Score: A Hockey Musical’

Share

This weekend offers two “event” movies, both quite out of the ordinary. One is Carlos, a five-and-half-hour multilingual epic about the world’s first celebrity terrorist. You can see the full version only in Toronto, at the TIFF Bell Lightbox (a two-and-a-half hour version will show in Vancouver). And though Carlos was produced as a mini-series for French television, I recommend you try to see it on the big screen. It’s a trip. Venuzuelan actor Edgar Ramirez gives one of the best performances you’ll see all year, speaking five languages, and transforming himself with a weight gain on a par with Robert De Niro in Raging Bull. If there’s any justice he’ll get an Oscar nomination. If you don’t have the access or inclination to see the theatrical version, this is one well worth catching up to on DVD.

The other event is less rare, and more parochial, but still no everyday occurrence: the ambitiously wide national release of a heavily promoted Canadian movie. Michael McGowan’s Score: A Hockey Musical opens on 130 screens across the country, which is a record for distributor Mongrel Media (also the nervy outfit behind the release Carlos). That’s double the number of screens that Mongrel booked for One Week, McGowan’s previous Canadiana confection. It’s almost up there in the Men With Brooms stratosphere (MWB opened in 150 theatres in 2002). Score‘s shameless attempt to pander to nationalist sentiment owes something to movies like Men With Brooms and One Week, as a reflecting-Canada-to-Canadians movie designed to play exclusively within our borders. But as a hockey musical, it stakes out a genre no Canadian movie has attempted. Score wears its national identity on its sleeve so proudly it’s hard to separate the movie from the marketing—there are times when this goofy celebration of Canada’s game plays like a jingoistic jingle. To not love Score feels almost unpatriotic. But my opinion doesn’t matter. I know this because a representative for the film told me as much. “You’re not the audience,” she said, after I’d seen Score at the Toronto International Film Festival and expressed some reservations. Hey, I would like to think I’m part of the audience, but apparently I’m not The Audience. And certainly wasn’t part of The Audience at TIFF’s opening night gala premiere, where Hawksley Workman blew the roof off Roy Thompson Hall after the closing credits when he performed a sing-a-long version of the soundtrack tune Hockey, The Greatest Game in the Land, backed by a children’s choir and a blistering drum line. (It’s on YouTube.) Had I been there I’m sure I would have drunk the Kanuck Kool-Aid like everyone else and emerged a convert, running into the night singing lyrics like: “It’s part of our hearts, part of our psyche/Our country bleeds red, white and hockey.”

But alas, I saw Score at a press screening full of jaded critics. For me, it was only a movie. I didn’t love it, didn’t hate it. Felt it was wildly uneven. But if the filmmakers and distributors are correct, critical opinion doesn’t mean squat in this case. The audience will deliver its resounding verdict at the box office. And then we’ll see if the country’s ardent belief in Our Game can overcome its chronic disbelief in the power of Canadian movies to entertain us. If Score does score at the box office, I suppose that counts for a lot. But there’s no excuse if it doesn’t. This film is fuelled by a strong release, a ton of promotion, not to mention a galaxy of cameo stars lining up with their support—including Nelly Furtado, Hawksley Workman, George Stroumboulopoulos, Evan Solomon, Walter Gretzky and Theo Fleury. At TIFF, I bumped into McGowan, the director, and promised to see Score with an audience before weighing in with a final review. Sorry, Mike, but I haven’t had a chance to do that. So for the record, here’s a slightly expanded version of what I wrote at the time of Score‘s TIFF premiere:

The notion of a hockey musical is both ingenious and outrageous, and much of the film’s charm lies in the sheer showbiz bravado of the concept, which is embodied by the central character—a home-schooled 17-year-old pacifist nerd named Farley (Noah Reid). To the dismay of his quirky, politically correct parents (Marc Jordan, Olivia Newton-John), Farley, who has never played team sports, is recruited to the big leagues by a wily old timer (Stephen McHattie). Overnight, he graduates from street-corner shinny to national stardom as the Next Great One, while mortifying hockey fans, and his coach, by refusing to defend his honour on the ice with his fists. Score is a meta movie, one that celebrates the fact of its own existence, wearing its post-modern concept like a team emblem. At its heart a terrific performance by Noah Reid. Not only can he skate and act; when he sings, he sounds like a young Paul Simon. And with an all-star roster of Canadian talent helping compose the songs, there are some good riffs to work with. But this is one hokey hockey movie. The lyrics are not as strong as the music. The cornball dialogue often falls flat. And the story goes way offside with a third-period resolution of the plot’s fundamental conflict that defies logic. Which is too bad. Because the script’s cavalier tone undermines the heartfelt conviction in Reid’s performance and in that of his young leading lady, Allie MacDonald. Even when a musical aims for outlandish farce, when hockey and young romance are in play, to engage emotionally, you still have to believe what’s happening. In the absence of believing in the story, or the characters, we are asked to believe in a patriotic equation between the Great Game and the Great Country. The result is not a great movie.

But here’s a YouTube movie of that Hawksley Workman sing-a-long:

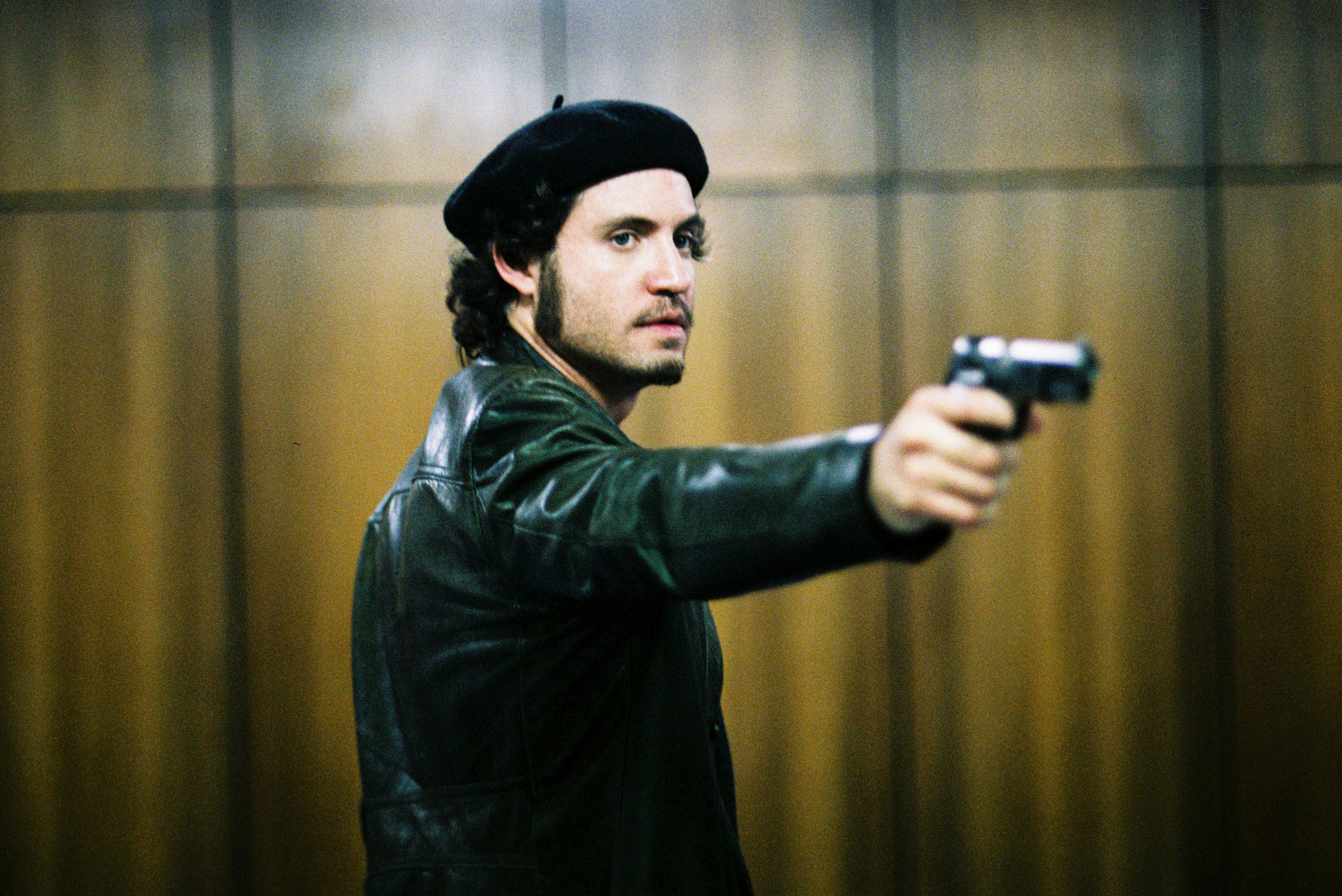

Carlos

What is it about iconic terrorists that inspires movies longer than five hours? First Che, now Carlos. Actually, as the big screen competes with home entertainment, I welcome the challenge of a marathon movie. It requires commitment. And although it may sound deadly to some, the experience of devoting half a day, or night, to a single film is more invigorating than you might expect. Especially in the case of Carlos, which is so relentlessly entertaining. Because of its presumptuous length, and the French provenance of its director (Olivier Assayas), it is necessarily branded an art house film, showable only on the margins of the mainstream. But Carlos is, in fact, a French wet dream of an action movie, propelled not by the romance of extreme politics, but also by cars, guns, cigarettes and sex. I could have watched Carlos on a set of DVD screeners provided by the distributor. But this was shot as a movie, in 35 mm, by one of French cinema’s most eloquent visual stylists. So I thought, hell, if I’m going to spend this kind of time I’d rather immerse myself in the luxury of the image, and the event. The last experience remotely like it was seeing the nine-hour marathon of Robert Lepage’s Lypsynch (2008), which positively bounced along on rhythm of four intermissions. You braced yourself for high art, and came out grandly entertained. Che had one intermission; Carlos has two. Carlos is a less spartan marathon than Che, but then Carlos was a less spartan revolutionary. If he’s a revolutionary at all. He’s a mix of movie archetypes: a Breathless gangster, seducer, cowboy, psychopath kind of terrorist, whose ego goes into Scarface overdrive and whose politics hang by a fraying thread of Marxist principle.

Venezuelan terrorist Ramírez Sánchez, aka Carlos and dubbed the Jackal by the media (a nickname he despised), was the world’s most famous terrorist before Osama Bin Laden changed the game. During the 1970s, after conducting a series of attacks in London, he was charged with running the European branch of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP). He coordinated a string of ambitious but bungled operations, from the Japanese Red Army’s hostage-taking at the French Embassy in the Hague in 1974 to the wholesale kidnapping of oil ministers at the 1975 OPEC conference in Vienna. Killing cops and detonating car bombs, he was terrorism’s version of a serial killer, but he was a megalomaniac, and eventually his PFLP masters, based in Yemen, lost their patience with him and cut him loose. Sánchez became a mercenary, a fat-cat fugitive hiring himself out to an ever-shrinking number of terrorist states, until the sponsors dry up and this homeless celebrity outlaw is finally betrayed, cornered, and captured. Sánchez is now serving a life sentence in a French prison.

Carlos conveys a strange sense of nostalgia—for an age of innocence when terrorists were more of a sideshow than a threat to global security. A gang of urban guerrillas who who can’t shoot straight simply stroll out onto the viewing deck of an airport, take a rocket launcher out of a bag, fire a missile at a plane sitting on the tarmac, and miss. This is an era where pay phones rule and everyone smokes everywhere at all times, even on the planes that are being hijacked. Virtually every dialogue scene in the film is choreographed around the lighting and smoking of cigarettes. At one point, when he’s overweight and washed up, this Marxist Marlboro man is smoking in the shower. And the life of this macho terrorist has plenty of room for sex as well as violence. Over the course of two decades, as his political allies come and go, so do the revolutionary gun molls, notably Magdalena Kopp (Nora von Waldstätten) a German feminist femme fatale whom he steals from a bloodless Stasi agent.

French filmmaker Olivier Assayas (Summer Hours) does a miraculous job of directing what amounts to three movies in 92 days on a mere $18 million budget. And it moves along like a freight train, with never a dull moment. Despite the length, the drama never seems padded. On the contrary it feels spare and efficient, as if propelled by it’s protagonist’s own insatiable drive. At the screening I attended, Assayas was on hand for a Q & A at the end, around midnight. He described Steven Soderbergh’s Che as “a kind of inspiration. It’s a very strong and fascinating film which uses a mythical central character to deal with abstract issues, and it’s a movie about strategy. About how you win and how you lose.” Both Carlos and Che won, then lost. Carlos is a far less honourable icon, a narcissist psycho in Marxist drag. But he’s a far more compelling character.