The Beaver and the Laugh Track

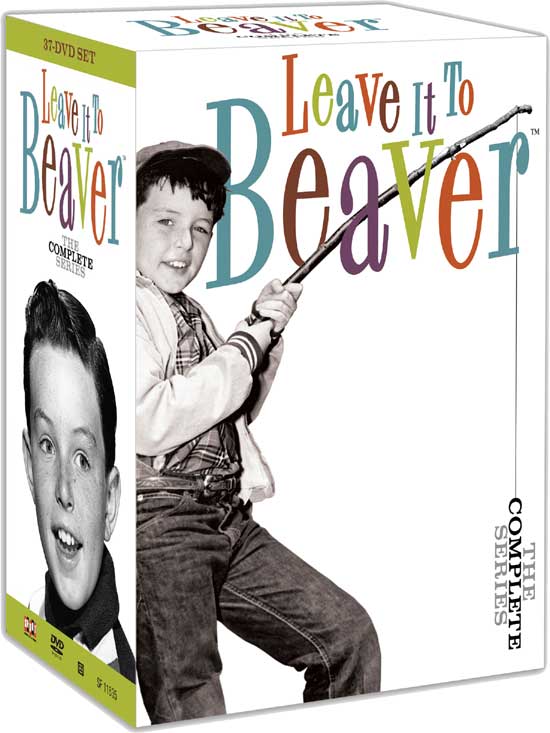

I’ve been spending some time with Shout! Factory’s complete Leave It To Beaver set, one of the most important TV on DVD releases of the year along with their upcoming complete Larry Sanders Show. The availability of all 230+ episodes, uncut and generally looking very good (black-and-white filmed shows often wind up looking better than colour shows as time goes on, and that’s definitely true of Beaver, which looks better than shows made 10 years ago), should help increase the reputation of a great show, one that used to be made fun of for reasons that were basically irrelevant.

Share

I’ve been spending some time with Shout! Factory’s complete Leave It To Beaver set, one of the most important TV on DVD releases of the year along with their upcoming complete Larry Sanders Show. The availability of all 230+ episodes, uncut and generally looking very good (black-and-white filmed shows often wind up looking better than colour shows as time goes on, and that’s definitely true of Beaver, which looks better than shows made 10 years ago), should help increase the reputation of a great show, one that used to be made fun of for reasons that were basically irrelevant.

I’ve been spending some time with Shout! Factory’s complete Leave It To Beaver set, one of the most important TV on DVD releases of the year along with their upcoming complete Larry Sanders Show. The availability of all 230+ episodes, uncut and generally looking very good (black-and-white filmed shows often wind up looking better than colour shows as time goes on, and that’s definitely true of Beaver, which looks better than shows made 10 years ago), should help increase the reputation of a great show, one that used to be made fun of for reasons that were basically irrelevant.

One thing that is striking about Beaver is that for a show that eventually became popular as a ’50s nostalgia piece, quite a bit of it is about adjusting to the modern world and modern values. Ward Cleaver is a new-school parent who was raised in a very different way, and is trying to figure out how to give his sons a good, moral upbringing without reverting to older ideas of parenting. When Ward mentions his own upbringing, he frequently mentions that his father believed in corporal punishment — that is, his dad made him a good person by hitting him when he was bad. This isn’t a thing of the past, either, because other kids in the neighbourhood refer to their parents doing more than just spanking them. (Beaver says in one episode that he’s glad he and Wally don’t have a “hittin’ father” like other kids they know.) Ward, like many people who were in the war — though he didn’t see combat, as Beaver learns after he tries to fabricate a story of his father’s heroism — has a different attitude about violence, and wants to bring his kids up right without being abusive (physically or psychologically) like his own dad.

There are also a lot of throwaway discussions about how times have changed since Ward and June were kids; a lot of their discussions turn to the question of what they did when they were that age, and how expectations were different for boys and girls. They’re not nostalgic or hidebound about it, they’re just acknowledging that things are different and that parenting is complicated by that: they can’t just look to their own past experiences to know what Beaver and Wally are going through. And sometimes Ward and June just completely blow it, even if their decisions are based on ideas that seem defensible. In the famous episode about the alcoholic handyman, Ward and June tell Beaver that the guy has a “problem” without ever telling him what the problem is. This leads to Beaver unwittingly helping the man get a drink (it’s 1960; everybody has liquor around) and fall off the wagon. And Wally confronts his parents with the fact that they caused this, by trying to shield Beaver from the realities of life. You could see that as being a point for the old ways of parenting — the idea of treating kids like “little adults” instead of the then-new fashion for treating them more delicately. But it’s more complex than that in the context of the episode, which makes a case for the importance of preserving Beaver’s childhood innocence (which, it’s suggested, may eventually inspire the handyman to get his life back on track) at the same time as it makes a case for not keeping kids too innocent.

In any case, the show is hardly a pure celebration of a perfect time; that’s something that was read into it after the fact, during the nostalgia craze of the ’70s. At the time, it was in part about a favourite ’50s theme: life is full of tough choices and people (kids, mostly, but sometimes adults) don’t always know exactly what the right thing is, even in “good” families. (A common plot pattern has Beaver or Wally interpreting some piece of advice their parents give them and taking a disastrously wrong turn with it.) Mostly, of course, it was about being a kid, and how your parents can guide you to the right conclusion but in the end, you need to figure some things out for yourself. Lots of shows have done the same thing, and some have done it equally well; none have done it better.

Another thing about Beaver that I find interesting is the way it uses that great bugaboo, the laugh track. I feel like the laugh track actually freed this show — and a few others — to be more subtle. Today, if you see a one-camera show, it’s often straining every muscle to prove it’s a comedy, meaning there has to be a joke every few seconds, and the acting has to be broadly comic. Because if a show doesn’t do that, it will come off as not a comedy but a half-hour drama, condemning it to failure anywhere except pay cable. But Beaver doesn’t have a lot of hard, “jokey” jokes, and the acting was pretty low-key a lot of the time. The writers and creators, Joe Connelly and Bob Mosher, knew that the presence of a laugh track would instantly brand the show as a comedy and identify the subtle jokes as jokes, so they didn’t have to punch up the jokes or worry about accusations that they weren’t really making a comedy. Beaver, like Andy Griffith a few years later, uses the single-camera format to be subtler than a Lucy-style sitcom could be, and uses the laugh track as a substitute for over-playing and other “look, we’re funny” clichés.

Among the extras are video interviews with cast members, an interview with the theme song composer, and various interviews from the baby boomer podcast Shokus Internet Radio. It also offers the unaired pilot of the show, which is famous because a very young Harry Shearer plays the role that eventually developed into Eddie Haskell. But the more disturbing thing about it is that Max Showalter plays Ward. If you’ve seen any movie with Max Showalter you’ll know he is one of the creepiest guys in film, and he doesn’t come off as any less creepy when he’s playing a suburban father. Knowing that he would go on to be the father in Lord Love a Duck, we can be thankful that the part was re-cast.