A well-balanced portrait of Cosmo editor Helen Gurley Brown

Helen Gurley Brown edited Cosmopolitan magazine for 32 years, during which she changed the way women talked about sex

Share

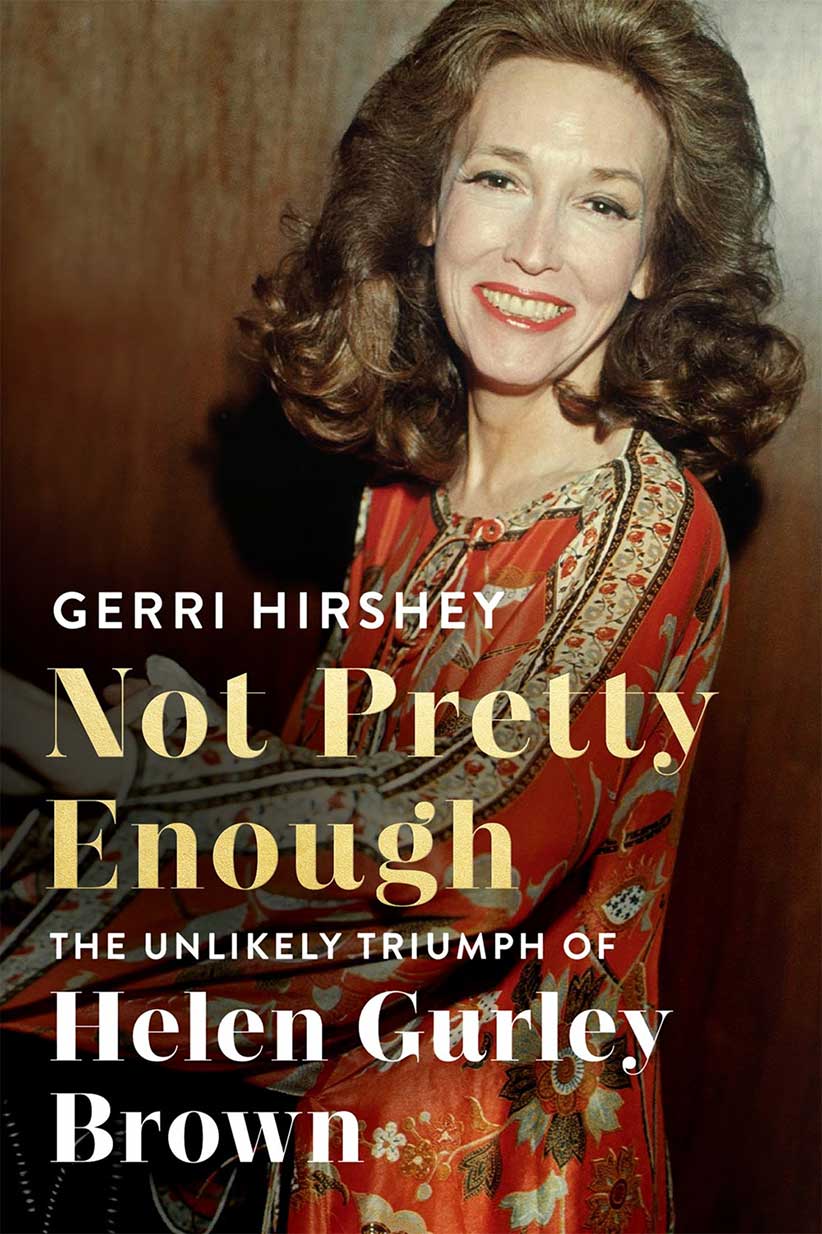

NOT PRETTY ENOUGH

By Gerri Hirshey

Mouseburger. Equal parts epithet and rallying cry, the cutesy neologism was coined by Helen Gurley Brown in her 1962 bestseller Sex and the Single Girl to describe plain, timid women, who are encouraged to break out of their shells and discover their full potential. Principal among them, vibrant proof of her plucky credo, was Brown herself, a fact she would loudly, gleefully trumpet her entire life, most notably in the pages of Cosmopolitan, where she served as editor-in-chief for 32 years.

Brown died four years ago, at age 90, yet she is already the subject of two biographies. Brooke Hauser’s breezy Enter Helen focuses almost exclusively on Brown’s heyday, from Single Girl through her game-changing revitalization of Cosmo, a moribund magazine transformed into the world’s most successful women’s title (now with more than 60 international editions in 35 languages). Gerri Hirshey’s Not Pretty Enough provides fuller, deeper examination.

Though Brown persisted in describing her Arkansas upbringing in terms of abject, hillbilly-accented poverty, hers was a middle-class childhood. After her father’s death in a freak elevator accident, the family decamped for Los Angeles. There, she endured 19 secretarial jobs before legendary adman Don Belding elevated her to copywriter. By the late ’50s, she’d become the highest-paid woman in West Coast advertising. Along the way, she said, she slept with 178 men, many married. In 1959, at age 37, she abandoned singlehood to wed Hollywood heavyweight David Brown (who would later produce Jaws). They became, says Hirshey, inimitably savvy pop-cultural “co-conspirators.”

Her reinvention of Cosmo drew praise—advertisers flocked, circulation soared—and scorn, notably from feminists such as Betty Friedan, who branded it “quite obscene and horrible.” Brown made important strides, championing birth control and abortion, and terrible missteps, including her insistence that AIDS was not a woman’s concern. Despite her massive success, she continually bumped the glass ceiling. When Hearst threw a lavish anniversary party in 1969, Brown, widely credited with saving the crumbling media empire, was excluded, told it was “strictly a stag affair.”

Brown’s was a life lived in exclamation points, both on and off the page, with its own kittenish vernacular (the nonsensical “pippy-poo” was a favourite adjective). Hirshey shapes a well-balanced portrait, ably capturing her Auntie Mame-esque élan and her lifelong insecurities, her winning of-the-people genuineness and her peccadilloes, and, ultimately, her triumph as a mouseburger that roared.