Ami McKay conjures witches

The Witches of New York is low on peril and high on plodding narrative

Share

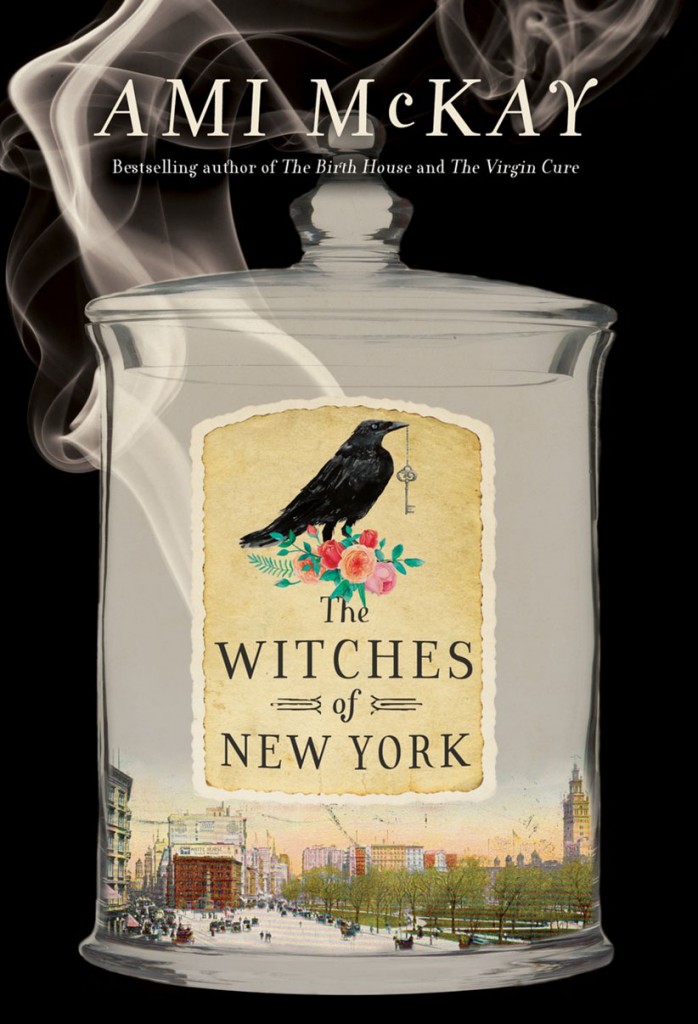

THE WITCHES OF NEW YORK

By Ami McKay

The Salem witch trials were, to be sure, a nasty, misguided affair. But in The Witches of New York, Ami McKay—whose 2007 debut, The Birth House, was a No. 1 bestseller and Canada Reads finalist—overcompensates for past misrepresentations by declawing her titular subjects to the point of dullness. Eleanor and Adelaide (Moth from McKay’s The Virgin Cure) have so little mystery or menace to them that they might as well be running a Midtown Starbucks instead of the quaint teashop where they discreetly provide potions and tarot readings to the female one-per-centers of Gilded Age Manhattan. Even the novel’s legion ghosts have an air of insipidity. Eight years after his death, we’re told the bored ex-proprietor of the posh Fifth Avenue Hotel “still hadn’t mastered the best way to go about the business of being dead.”

Witches are typically agents of transformation, so there’s an unfortunate irony to the fact that no character—witch or otherwise—changes in any meaningful way over the novel’s 500 pages. We expect it of the 17-year-old orphaned ingenue Beatrice Dunn when she arrives from her aunt’s upstate manor in hopes of putting her unusual gifts to use. Indeed, the teashop has an unleashing effect on her: as soon as she’s through the door, Beatrice is seeing so many dead people she’s not sure who’s actually alive. Still, it’s an atmosphere more Snow White than Sixth Sense, especially given the presence of a talking raven and two mischievous fairies.

But other than abetting a tepid love story between Adelaide and the dashing Dr. Quinn Brody—an “alienist” whose interests turned to the spirit world after he lost his surgeon’s arm to gangrene—Beatrice’s main function is as prey for the novel’s pancake-flat bad guy: a Westboro Baptist Church-style minister who grinds the axe he’s got for witches by slashing their throats in alleyways.

Quinn himself is a “progressive” and—in regard to women’s ability to channel the paranormal—“a man who believes women” (one of several heavy winks to contemporary catchphraseology). Eager to convince the skeptics and to arrange a chat with his dead dad, Quinn gets Beatrice to agree to a public demonstration of her talents via his “spiritoscope” machine.

A plodding narrative is unnecessarily prolonged by endless banal interactions between characters. If The Witches of New York evokes a sense of peril, it’s the fictional peril of telling instead of showing, of trying to describe the mind-blowing with the language of the mundane.