Carly Simon on Mick Jagger, Taylor Swift—and being herself

The 70-year-old singer-songwriter opens up about the kind of life she’s lived

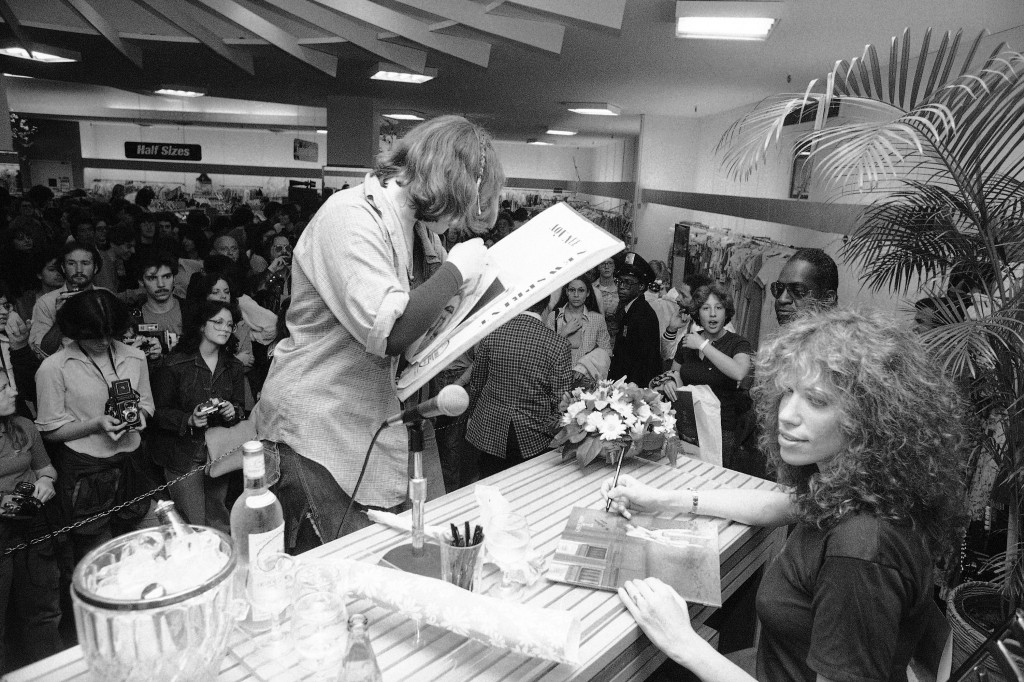

Carly Simon is photographed in New York on April 24, 2008. (AP Photo/Jim Cooper)

Share

On Carly Simon’s latest album, Songs From the Trees, the 70-year-old singer-songwriter offers a few hints on the kind of life she’s lived. The 30 songs she carefully plucked from her five-decades-plus career (taken from 25 studio albums) beautifully map out her eccentric family life, her perplexing coming-of-age and all the challenges that singledom, marriage and divorce bring to the table. This rich sense of nostalgia also informs Simon’s just-released memoir, Boys In The Trees. Here, the Grammy- and Oscar-winning artist opens up about both projects and fills in a few gaps.

Q: You once described recording “You’re So Vain” with Mick Jagger as being a transformative experience—a session where you both “became Narcissus at the mic.” Describe the type of passion that made this track such a classic.

A: There was something about the way we saw each other while we sang. At that time in our lives, we had an uncanny physical resemblance to each other—especially our faces and our lips. We stood at the same height and we were both lanky. In the waxy top of the ebony piano, there was a veneer that was just like a mirror. There was a reflection on it, which just blurred the outlines of our faces so you couldn’t tell who was who. We were looking at each other the whole time. It certainly had a heat—and a power—that keeps lasting.

Q: In Boys In The Trees, you wrote about how your mother wasn’t by your father’s side when he was suffering from depression and heart disease. Instead, she took a live-in lover. How do you think witnessing this so early affected your own relationships?

A: I grew up not understanding what was true and what was not true. It gave me a sense of unreality. I was told that this man was not my mother’s lover—when he was. I was told he was there as a male babysitter for my brother so that he would learn sports and other manly things.

Q: Does living through all that have an effect on your songwriting?

A: Probably. My mother was so ahead of it in many ways. She broke the Stamford colour barrier in 1954 [Jackie Robinson was a frequent guest of the Simons]. Also, I remember my mother saying to me at seven, “I wish I was a lesbian,” and I didn’t know what that meant at all. She explained it to me, and I remember chewing the cud on that. I remember writers being at our house when I was young—I remember Dorothy Parker called me over and said, “Come over here dear, let me tell you a story,” but I can’t remember what the story was.

Q: More than 30 years ago, you wrote about open marriages in “No Secrets.” Some of the lyrics in the song, such as “You always answer my questions but they don’t always answer my prayers,” sound directly aimed at your first husband, James Taylor. Did he know?

A: I think James and I read between the lines about all our songs. There was this unspoken agreement that we did not have to delve into certain issues. We allowed each other a poetic licence … that we really appreciated in each other. I believe there is a certain part of oneself that is inviolable.

Q: After you did an interview about winning an Academy Award for the single “Let The River Run” (from the Working Girl soundtrack), you said, “Winning an Oscar is like having a baby; it probably comes with postpartum depression.” Was it?

A: No, it came with elation! I had pre-Oscar anxiety. I was terrified of flying to L.A., and then there was the tension of being nominated and not winning. I thought I’d feel like a fool if I [attended] and I lost. You have to know that those people sitting in the auditorium feel horrible [when they lose]. They don’t really feel like, “Oh that’s wonderful that that other guy won.” I went to see a doctor beforehand and he put me on Prozac—remember Prozac?—and I made it to the plane, the auditorium and the stage and won the Oscar. I don’t know if it was the Oscar or the Prozac, but I was okay and had no depression for three years after that.

Q: Another triumphant moment for you was your comeback hit, “Coming Around Again”—which became an anthem for many divorced women. Did it reflect the times?

A: Well, it’s about the myth of Sisyphus. He is [a Greek king] who keeps rolling a boulder up a hill, and it keeps getting away from him and rolling back to the bottom of the hill. Then he pushes it up again. It also reflected the story of Nora Ephron and Carl Bernstein’s marriage, which inspired the song because I wrote it for the [soundtrack to] to the movie Heartburn, [which was based on their relationship]. It could have been a very weepy song ending but I [incorporated] “The Itsy Bitsy Spider” and sang it to the same accompaniment as “Coming Around Again.” So it ended up having this wonderful feeling about it. I’m interested in the human spirit—which, to me, is about having that never-ending hope.

Q: Songs From the Trees includes the track “After The Storm” from Playing Possum—an album that predated Madonna’s Erotica as it unabashedly tackled sexuality from a woman’s point of view. Did you know you were pushing the status quo when you recorded that?

A: I just went with my ears. “After The Storm” was a Brian Wilson-like experiment. I love that song. It was just me putting my fingers down on the piano and seeing what would happen. [Oscar-winning musician] Jack Nitzsche had heard it and called me up and started asking me how I thought of certain chords.

Q: What were the side effects of releasing an album that brazenly talked about sexuality in its lyrics?

A: I was shamed because the song “Slave” was seen as not feminist, because, you know [the lyrics state], “I’m just a slave for your love.” I was trying to say, “Dammit, I’m not happy about being a slave to your love but I am!” When it came to interviews, sometimes I would get annoyed. Often I would just say, “This is the way it is.” Some people needed to be talked through the themes. I had to learn that there are some people who aren’t at the same level I’m at—whether I’m more advanced or backwards.

Q: There are still so many double standards in pop. For example, Drake’s “Hotline Bling” has him singing about wanting “a good girl” who waits by the phone, stays at home, doesn’t go out. Do you think women could get away with writing these types of infantilizing lyrics?

A: No. Of course not.

Q: So why do you think, in 2015, men are still singing about having virginal partners?

A: The advancements that women have made are very threatening to men in the job place. There haven’t been that many women in politics. If you look at the conventions, it’s kind of pathetic how many men are the heads of companies. On the other hand, I’m not sure what the reality should be. All men are created equal and all women are created equal as well, but [equality] seems much clearer when it comes to race issues. In the realms of man/woman, man/man, woman/woman love, it seems all up for grabs now. We are exploring so much, but I think we gotta go for the fight for all equality first. I’m a little old-fashioned—I like it when the man opens the door and I like it when a man pays for me. I particularly like it when they pay for dinner or whatever, because I’ve pretty much done the opposite, but for the exception of James [Taylor], where we split everything down the middle. I’ve been the larger money earner in practically all of my relationships. There’s equality and there are positive differences, which are complimentary.

Q: You are often called a feminist icon. Did you feel the feminist movement was in your corner for most of your career?

A: I never identified with the feminist movement in a strong way. I just kind of lived it. I didn’t politicize it. I didn’t follow any written rules to what it meant to be a feminist. I had my own sense of what was right and wrong.

Q: In the book, you write about some very uncomfortable encounters you had with male producers and musicians—including Marvin Gaye and Redd Foxx. They wanted to get physical with you in the workplace. From what I read, you seemed to have a handle on dealing with these kinds of guys. Did you ever fear that you’d be sexually assaulted?

A: Well, there were a couple of cases where I was sexually assaulted that I didn’t write about in the book. I took an overly reasonable and non-combative stance because I was afraid what fighting someone off would do. I was afraid that things would get a lot worse.

Q: In a song called “Tired of Being Blonde,” you sing about being tired of “living up to all he expected/looking like a cutie on a magazine” and “chasing all the latest sensations.” Was this a metaphor for the music industry in 1985, when the track was released?

A: Interestingly enough, that song was chosen for me—I didn’t write it. Spoiled Girl was the album I felt most put-upon. It was directed that I do those songs. I was told who to work with as a producer. After Spoiled Girl—which was a flop—I was given an ultimatum by my then manager. He said he’d gotten a good deal for me with Clive Davis—which was a $100,000 advance. I found out later it was an advance that should have been $2,000,000.

Q: Poetry kick-started your career because you started singing to help you memorize a poem you were assigned to recite in class. What poets do you keep reading now?

A: My favourite is my ex-husband Jim Hart. He’s an exquisite poet and my second husband. I tend to go for the Irish poets: Yeats, Dylan Thomas and, of the American poets, William Carlos Williams. I also love Auden. I’m a big fan.

Q: In your memoir, you mentioned your ex-boyfriend, novelist Nick Delbanco, and your ex-husband, James Taylor, felt slightly competitive with you. Did you also feel the need to compete with them?

A: With Nick, he felt worried I would leave him, if and when I was loved by a larger audience. With James, there was a positive competition in our work. We always tried to better the other. I always felt he bettered me no matter what he did because I looked up to him so much.

Q: When you hear of artists like Taylor Swift getting criticized for her songs about relationships, do you have PTSD?

A: She’s told me that she gets raked over the coals. But anybody who’s as successful as Taylor is going to get raked over the coals for one thing or another. She could have gotten it for writing about mashed potatoes and the perfect gravy. She’s so wonderful that she was born for the job. She’s the perfect species for this time—in this century. She’s the ideal girl. Which is why they want to rake her over the coals.

Q: You’ve battled stage fright for years and put off doing so many world tours because of it. Was there ever a time you thought performing live was easy?

A: I never remember it being easy. I’m so hyper-aware of how my body feels all the time. This book I read recently called Too Loud, Too Bright, Too Fast and Too Tight has told me my nervous system is overexposed and it’s not made for the stage. It’s like somebody whose eyes can’t go out into the sun because they are too sensitive to the light.

Q: Are there things you did to help you quash your issues with performing live?

A: I’ve done all kinds of things. Once I flew this guy in to play an instrument called a didgeridoo, right on my belly, to calm me down. I didn’t write a chapter called Floundering in the book—to explain all the ways I have tried to combat this problem. I’ve tried everything. I had one therapist who ended up sending me a bill for $16,000 for a one-hour session just because he could. He made me stand in a room with my arms out and go around counter-clockwise saying “I love performing! I love the stage! I’m fine, I can do this!” So I have done kooky things to get over it.

Q: Lady Gaga recently talked about how she almost quit music because she became a money-making machine, creating products that didn’t feel were true or real. Is this something you can relate to?

A: I don’t think I’ve ever had an image that doesn’t correspond to something I feel comfortable with. I don’t have a persona. I didn’t have any trouble from the record company when it came to my image. We were generally in sync. They didn’t push me to have a sexy image. I tried to have a sexy image to compete with my sister, on my own. Even at the age of seven, I was always trying to look alluring to capture the attention of my father, who was also a photographer. I wouldn’t feel right putting on a lot of makeup or special clothes for the stage that had frills, feathers and masks. A lot of artists like Madonna and Lady Gaga have personas, and it makes it easier to get on stage because they don’t have to be themselves. I don’t know how to not be myself.