How Prince, rock’s effortlessly dangerous star, changed the game

Remembering the life and times of Prince, and why the loss of this iconic musician, at the age of 57, is so momentous

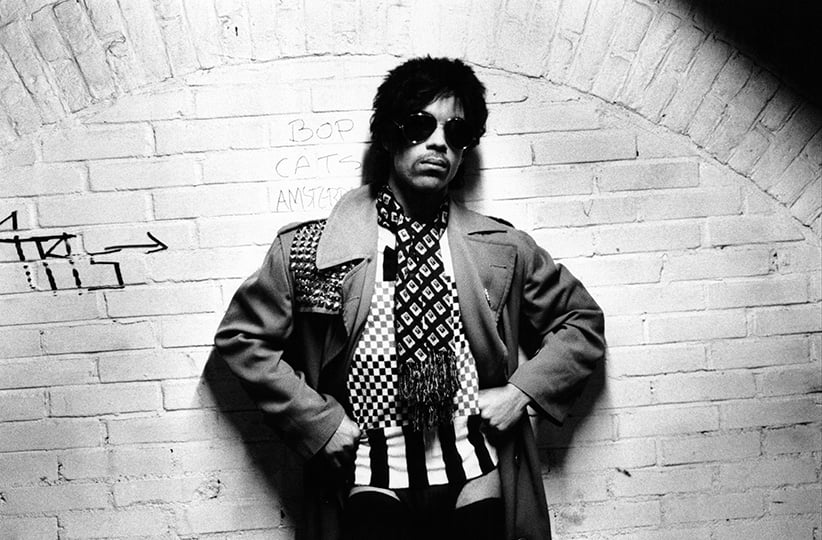

Posed portrat of Prince. (Virginia Turbett/Redferns/Getty Images)

Share

Life is just a party, and parties weren’t meant to last. The man born Prince Rogers Nelson died this morning at age 57, at Paisley Park, his Minneapolis residence that doubled as a studio, office and nightclub. Bizarrely, the man who once vowed not to “let the elevator bring us down” in his most life-affirming hit (Let’s Go Crazy) was found dead in his own elevator. The cause of death is still being investigated, but is expected to involve prescription painkillers he was taking for his hip—damaged after years off leaping speakers in high heels.*

There is simply no musical figure of the last 40 years who commands the same respect as the notorious and eccentric Prince. He sold more than 100 million records, wrote hits for other people, and his songs are staples of playlists for weddings or any celebratory occasions. That is rare, but by no means unusual. More important, you will not find a musician in the Western world who will not at the very least concede Prince’s musical mastery; to many, he was the most innovative, creative and technically skilled musician of his generation—as a guitarist, a vocalist and producer. At the age of 19, he was signed to Warner Brothers and somehow convinced them to let him play all the instruments on his 1978 debut album himself—something that, at that point in time, only someone at Stevie Wonder’s level would even attempt.

Prince was second only to Michael Jackson—they were both born in 1958—as an African-American who bridged cultural divides by exploding expectations of what pop music could be. But whereas Jackson needed someone like Quincy Jones to shepherd his musical vision, Prince was everything in one: steeped in soul music and new wave synths and jazz and psychedelia and Joni Mitchell and disco and—oh yeah, he could shred on guitar in ways that would send all those L.A. metal posers back to school. Prince may have had to share his 1980s superstardom with Jackson, Bruce Springsteen and Madonna, but he was easily—and seemingly effortlessly—the best of all of them in one package.

He was also the most dangerous. The term “rock and roll” itself was originally a euphemism for sex, but Prince was libidinous and libertine in ways mainstream America had never seen. He posed on album covers in women’s underwear (Dirty Mind), or completely naked in a white orchid (Lovesexy)—or naked while riding a white winged horse (1979’s self-titled album). His first hit single was called I Wanna Be Your Lover—and he wasn’t kidding. Nearly every song was about seduction, often smutty enough to raise the ire of concerned parents. The Roots’ Questlove has talked about buying multiple copies of 1999 because his father would break any copy found in the household. Most famously, it was Prince’s Darling Nikki—a song on Purple Rain about a seductress who “likes to grind” and is found “masturbating with a magazine”—that Tipper Gore heard coming out of her teenager’s bedroom. It led directly to the formation of the Parents Music Resource Committee, a group of “Washington wives” that held congressional hearings about pop’s turn toward the pornographic. Compared to R. Kelly—hell, even Nickelback—Prince seems quaint today; with few exceptions (the extremely uncomfortable Lady Cab Driver, for starters), he doesn’t play the arrogant, conquering seducer, but a lover who’s more interested in your pleasure than his. (The Weeknd, among other modern Lotharios, should be taking notes.) Women, not girls, ruled his world. One of his greatest songs is a gender-bender called If I Was Your Girlfriend. One of his biggest hits, I Would Die 4 U, boasts, “I’m not a woman / I’m not a man / I am something you will never understand.”

Like David Bowie, Prince seemed to be an avant-garde alien, a trend-setting musical polyglot who acted as if gender and race—indeed, identity in general—were fluid concepts. His 1980s backing band, the Revolution, was the only major act—before or since, really—other than Sly and the Family Stone to boast a multi-racial lineup where women played lead roles. Unlike Bowie, Prince rarely granted interviews, especially at the height of his fame, which only increased his mystique. And really, what could he possibly say that would make him more interesting?

Related: Maclean’s interviews Prince in 2004

Prince released 10 albums in the ’80s; only one of them could be considered superfluous, the nonetheless massively successful soundtrack to Tim Burton’s 1989 Batman movie. He won Grammys and an Oscar for his 1984 breakthrough, Purple Rain (the last three tracks of which, including the epic title track, were recorded live in the Minneapolis club where the movie was filmed). His 1987 album Sign O the Times wrote new rules for R&B, its influence having bounded back in recent years in the work of Miguel, Kanye West, Frank Ocean and Drake; its title track was covered by none other than Nina Simone, on her final album. On the 1993 compilation The Hits/The B-Sides, the one disc’s collection of castoffs—including a version of a Prince song that Sinead O’Connor turned into a hit, Nothing Compares 2 U—is every bit as excellent as the chart-toppers (see: Erotic City).

Then things got weird. In 1993, he started warring publicly with his label of 15 years, Warner Brothers, who refused to release albums at the pace preferred by the prolific Prince. Except that he was no longer Prince: he’d “changed his name” to an image combining the astrological symbols for Mars and Venus (which also served as the title of his 1992 album), because Warner held the trademark on the name Prince. Over the next two years they squeezed three more albums out of that contract, including the once-shelved 1989 curiosity known only as The Black Album, and the underrated Come. (As a joke, Canadian musician Bob Wiseman, also signed to Warner at the time, tried unsuccessfully to change his name to Prince.) To the chagrin of writers and broadcasters everywhere, he insisted that he be referred to as “the Artist Formerly Known as Prince”; print outlets were provided with a floppy disc with the glyph on it. He was one of the first artists to take his fan base to the then-nascent Internet, selling online-exclusive releases, like the 3CD set Crystal Ball, containing material from his vaults that he claimed Warner Brothers didn’t want him to put out. From then on, he partnered with other major labels for one-off album deals.**

All of that, of course, made the massive pop star appear spoiled and greedy—and bonkers, especially when he took to writing the word “slave” on his face. Of course, it looks entirely prescient; now it’s routine for major artists to eschew major labels and go it alone. Two decades later, Prince would be a major supporter of Jay Z’s Tidal streaming service, praising it for being the only such product to prioritize artists over money men.

The next year, 1996, he married his girlfriend of four years, Mayte Garcia; they had a baby boy who died seven days after birth, from a rare skull defect. He granted Oprah Winfrey a strange tour of his Paisley Park mansion a week later, showing off the crib as if nothing had happened. Mayte later had a miscarriage, and the marriage fell apart shortly after. Prince remarried in 2001, to Torontonian Manuela Testolini, and bought a house on the city’s toniest street, the Bridle Path; they split in 2007.

His music became more erratic; his last two decades left longtime fans scrambling to find the moments of brilliance (and there were many) scattered across 16 studio albums. Younger audiences were hard-pressed to find his music online: the old-school artist was notoriously litigious if anyone uploaded his material to YouTube, clinging to the (sadly) now-obsolete notion that music was worth paying to hear. But his 2007 SuperBowl half-time performance almost single-handedly resuscitated his career, and the demographic of his still-legendary live shows started skewing younger. His output never waned: Prince remained committed to new work, releasing four albums in the last two years alone, including one with his new band, 3rdeye Girl, featuring Torontonian guitarist Donna Grantis. Even his most hardcore fans had trouble keeping up with his output. His final album, HitNRun Phase Two, was officially released a week after his death; it features the #BlackLivesMatter protest song Baltimore—a politically explicit rarity in the catalogue of an African-American artist once marketed as being of mixed parentage and who, in 1979, told his record company, “Don’t make me black.”

Great musicians, iconic musicians, die every month. Prince is different. Not because he’s one of the last of an era, from a time when young musicians practised for endless hours and learned their craft night after night on stage before they recorded a note of music. No: It’s because Prince is one of the few musicians, like Miles Davis or James Brown, who broke new ground and changed the course of popular music—not just in terms of appeal, but the way it’s made, the colours it uses. Unlike so many geniuses who went either unrecognized in their time or only appealed to a niche audience, the anomaly that was Prince—like only the Beatles before him—somehow managed to be massively successful while doing so. And he did so in a time when there was still a shared mainstream culture that made it all that much harder for outsiders to break through—especially if you happen to be a dwarfish black man from a snowy northern town, articulating your dirtiest sexual fantasies while wearing women’s underwear on stage and singing in falsetto and wrapped in lace and playing hard rock guitar with jazz skills and somehow convincing Hollywood that you should star in your own biopic at the age of 26.

It’s beyond bizarre that Prince is dead when so many of his heroes—progenitors and equals—are still alive: Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Sly Stone, Joni Mitchell, George Clinton. Yet Prince likely recorded more music than those five put together, and we’ll be wading through it for generations to come. Long may we bathe in his purple reign.

Correction: The first version of this story incorrectly identified his hometown as Milwaukee. That is… embarrassing.

* Altered to reflect developments in the weeks after his death, which was initially suspected of being from the flu.

**This paragraph has been edited to correct chronological errors.