Meet Poo Bear, Justin Bieber’s—and pop’s—not-so-secret weapon

As an elite topline writer, Jason ‘Poo Bear’ Boyd has produced a pile of pop hits. So why does he still feel like he has plenty to prove?

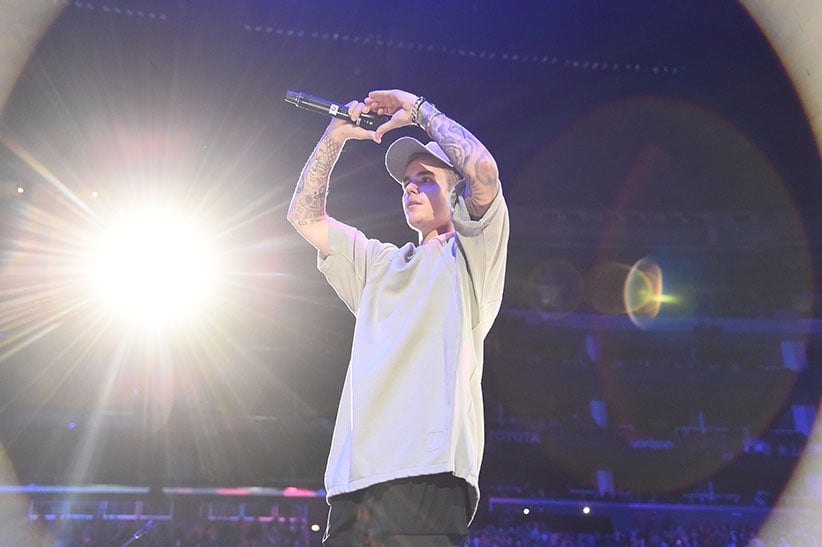

Jason “Poo Bear” Boyd poses for a portrait in his house at Sunset Strip in Los Angeles, California on July 11, 2016. (Dustin Downing/Red Bull Content Pool)

Share

When Jason Boyd—better known as Poo Bear—greets you, it’s cheerfully, if anachronistically: “Happy birthday.” When he says that to me from Los Angeles, it’s early May; my birthday is in July—which he couldn’t have known, anyway—and his isn’t until September, and he admits he prefers to keep his birthdays low-key.

But as a new documentary, Poo Bear: Afraid of Forever (out now on Red Bull TV) reveals, the reason behind his go-to salutation—”you know that feeling you get in the morning when you wake up on your birthday? You’re supposed to feel that way every day”—is reflective of a man of contradictions whose path to songwriter greatness has been quixotic but determined, amiable but hungry, this sonically omnivorous wanderer who’s meeting his big moment with odd discomfort.

After all, this is a man who has plied his trade for nearly two decades in the shadows that are typical of topline writers, helping on chords, lyrics, concept, and melodies that’s usually credited only in nearly anonymous liner notes for the likes of Usher, Chris Brown and Kelly Rowland. And while he’s won four Grammys and has scored four Billboard Hot 100 number one hits, no one really knew his name. But in the last couple years, after receiving public shoutouts from Justin Bieber for helping write smash hits “Where Are Ü Now” and “What Do U Mean”—he met Bieber at a 2013 party in Vegas and they quickly became friends—he’s begun to be recognized as a top producer, with atypical longevity in his field; his first big breakthrough came with the 2001 hits “Peaches and Cream” and “Dance With Me” by 112, and scored two Billboard number one songs this month by co-writing DJ Khaled’s summer 2017 smash “I’m The One” and assisting on Daddy Yankee’s “Despacito.”

Somehow, though, despite all the accolades, he admits he’s still afraid. That’s because the pop-music industry is cutthroat, a business that constantly asks “what have you done for me lately,” and where the behind-the-scenes songwriters and producers are often seen as disposable, chewed up and spit out in favour of the new young hotness in, on average, around four years. “One day, you’re looking up, trying to write another hit, and then you gotta end up getting a regular job,” says the 37-year-old. “That’s scary.”

In an interview with Maclean’s, Poo Bear talks about what makes a great pop song, shares his personal experiences in a ruthless music industry, gives advice to up-and-coming songwriters, discusses why songwriters might not want to seek fame, and explains what it was like being by Bieber’s side during the pop star’s year of arrests and controversies.

Q: I’ve written about music for some time, and you’ve been in it for nearly 20 years; you and I know that making a pop song is collaborative, with top-line writers, producers, and artists working together. But the average listener usually doesn’t know that. Does that surprise you?

A: No, it doesn’t surprise me, because I feel like it’s no different from a movie. Movie actors are acting, and they’ve taken a script that somebody else has written. It’s very similar. So it’s not surprising. Just because people want to believe what they see, and want to believe what they hear, and they definitely want to believe that it’s coming from that source, you know, in order for them…because they connect with that artist, they connect with that actor or actress, they connect with that character in the hopes that it’s really coming from them. And it’s not surprising at all that people still are kind of in the dark about that.

Q: And I’m sure you’ve heard this simplistic, common criticism of pop music: “Oh well, the person didn’t write it, so it’s not as good.” Have you heard that kind of criticism before?

A: I have, but I mean, here’s the thing. For me, most of the stuff that I’m doing with artists is a collaborative effort. So whether every line comes from the artist, for me, we still need the artist to get this great music out there. And you know, what’s a song without somebody singing it? It’s just a song. And then vice versa, what’s an artist without a song? It’s just an artist. And they go hand in hand. So you hear the criticism, but it’s like, great music is great music.

Nobody ever questioned Michael Jackson. You know, all of his hits were written by other people. So it’s just certain levels you get to where it’s acceptable, and it’s not. Nobody ever questions Bono, U2, or…there’s certain artists that make it to a certain level. And it’s not about who’s creating it—it’s about the product. Nobody cares who’s creating, you know, bleach or Tide when you wash your clothes. You just wash the clothes—it’s just a great product. So I just think that the criticism will always be there, but at the same time, good product is good product, no matter where it’s produced or created. It’s just great product. It should be out there for the world.

MORE: What’s a topline writer? Inside the machinations behind pop music

Q: It’s funny that you call it a product—a lot of people who say pop music is bad, the criticism is often that it is commercial, as if that’s a bad word. But what makes pop music so great—or even art—for you?

A: It’s just being able to do melodies, along with great wordplay and a concept. It’s cool because it just reaches the masses. Pop music—deriving from the word “popular”—for me, it’s just great to be a part of music that reaches a large amount of people and not just a small amount of people. And it just has so much more meaning to be able to reach all across the world, more than it being locked into a certain genre or a certain demographic—pop music allows everybody to hear this, and therefore it’s more effective and more people get a chance to say whether they love it or not.

Q: When do you know you’ve got a hit on your hands?

A: I just had this conversation with my manager yesterday and honestly, sometimes I know, sometimes I feel it. And then sometimes I don’t know, it turns out—and my manager will hear it and he’ll be like, ”That’s the hit.” And he’s right, he’s always been right. But for me, as long as I’m sticking to my formula and using all the components that I used before on my other records that were good, I feel like there’s a chance, there’s a high percentage that, as long as the platform and the marketing and everything that’s set up around the hit song is there, then it can become actually a successful song. So I don’t really know, all I know is that I use the same formula, and I stick to what I love, and that has gotten me a great reaction from my songs in the past. And there’s times when you might think something’s a hit and it’s not a hit. Or there’s definitely times when you think something’s not a hit, and it’s a hit. So I can actually honestly say that I genuinely don’t know. I can just go off of what I feel, and what I love, but you never know how the people are gonna take the song, you just never know.

Q: Those Justin Bieber songs, did you get the feeling that those were hits when you top-lined those?

A: Us working together on those records, we had a feeling that they were special. And they moved us and we were happy and we loved everything, honestly. And we just felt like we just wanted to get this stuff out there. And we were hoping that the world would share that feeling, were open to that feeling, and it would be mutual for how we felt during the creation of those records. And it turned out okay.

Q: I’ll say! But you know, being a topline writer must be strange, when so many of your songs come from personal experiences you have, and then for it to be sung by someone else. You’ve been homeless, for instance, and have written songs around that. Or that song, “No Pressure,” a song you did with Justin—

A: Yeah, definitely, my wife—before we even got engaged, she broke up with me and that record started from that feeling. And I ended up going in and Justin came and completed the idea for me. But it definitely derived from my wife breaking up with me at that time. It was like, you don’t have to make your mind up because I really wanted to be back with her and I really wanted to move forward and be a good guy. And definitely those actual actions came out in those words.

Q: Is that a weird feeling?

A: It’s not weird, because it was me, it was a collaborative effort. Justin’s always a part of this creative process even if an idea came from me, and it was some words and melodies there, Justin always came in and added to it in every situation. So, it was weird but at the same time, he was involved, he was a part of it, we did it together. And some people could look at it strange, but I just feel like all great records are a collaborative effort, no matter how you look at it.

Q: And that’s true of other songs, not just the ones you’ve written with Justin?

A: Yeah—at the end of the day, the artist that I’m working for, creating for, has to connect with it and they have to be able to put their own interest into it, in order for them to be able to sing it and for it to be real. They have to add their own stuff in, put their flavour into it, so when people hear it, it does connect with the fans, and it does come from a place where it’s like, “Whoa, I can relate to that artist.” Whether the whole idea or concept came from that artist or not, just them being involved in any shape or capacity allows for the artist to connect with the song and to perform it even better. And for the artist, and for the public, and the fans to connect with the artist. Just because they did have something to do with it, and it’s their voice, and they do agree with the feeling or they wouldn’t be singing it if they didn’t agree with what it was saying. So I definitely can still relate to the artist singing the words, even if they all didn’t come from the artist, it’s still a collaborative effort.

MORE: The faith and reclamation along Justin Bieber’s redemption tour

Q: You talk in the documentary about how songs are inspired by “dope concepts.” So—and maybe this like asking for the KFC special spice blend—what makes a “dope concept”?

A: For me, what makes a dope concept is it’s a fresh idea, something that I’ve never heard before. And so many songs, so many cliché concepts that when for me—if I’m in conversation or wherever I find my concepts from—to me that makes an amazing concept, just because it’s like stumbling upon a new discovery. And it’s like discovering a new planet, like “Whoa, I’ve never seen that planet before and nobody’s ever seen that… Let me introduce this planet that I just discovered to the rest of the world.” It’s something that’s simple and effective, that’s a complete thought within itself. Or, a concept that has a double meaning, a double entendre that might mean some people might take it one way, some people might take it another way. And ultimately, it might mean both things. So those for me, those are things that make a great concept.

Q: At one point in the documentary, the producer Matoma calls you a legend. Do you feel like one?

A: I don’t feel like a legend, man. It’s weird. That’s a great question. I don’t feel like—it’s weird because I always…I think it’s a normality for people to equate legendary-ness with age, and I think I’m a victim of that. Like, me feeling like I’m 37, I know I’ve done a lot of great things in my life and I’ve accomplished a lot in my life, and I just don’t know – I just feel uncomfortable calling myself a legend. I feel like if somebody comes to that conclusion on their own, then that’s cool. But for me, I wouldn’t call myself a legend, I just feel like I have so much to do. I feel like I’m just getting started. I’m just now tapping into something that can turn into something that’s legendary, but I just feel like…I don’t feel like a legend, man. Like I don’t. I just feel like I’m just beginning, I feel like I’m learning and I’m growing. I honestly don’t feel like a legend. When people say it, it’s even weird to hear it.

Q: It’s funny that you bring it up, because for me, you’re right, I think of a legend, I think of someone who’s hit the prime already, and it’s like a past tense kind of character.

A: Yeah like, 70 years old…like Forrest Gump. Like, 20 years in, it’s cool, it’s definitely longer than the average writer, producer, but still—I just feel like I have so much more to do in life. And honestly, I don’t know if I’ll ever feel like I’m a legend. People say to me, “You’re a genius, you’re great.” I don’t know if I’ll ever feel that way about myself. Some things I feel like are better left for other people to say, and I’m just not into like, tooting my own horn or bragging or anything. I just feel like I have so much more to do in life. And even once I’ve done so much more, I don’t even know—I’m not even sure if I’ll feel like I’m a legend at that time.

Q: And then the flip side of this legendary quality is that you get recognition and fame. Is that something you even wanted?

A: No, I never wanted that. Justin’s the first person to mention my name and to speak really highly of me on different interviews and stuff and that was weird, because I was so used to people taking credit and not sharing credit with me. It was almost like, “you don’t have to do that.” And he was like, “No, I want everybody to know that we did this stuff together.” And it was definitely strange for me cause I never really cared, I never wanted to be famous. I understand that it goes along with building a brand, and allowing you to go and charge more and everything, but for me—I always just wanted to be able to just buy my mom a house, and take care of my family. I never really felt like I had to be famous in order to do that. I just felt like I had to work really hard. So I never really wanted to be famous and I never expected anybody to put me out there like that. So Justin’s definitely the only person to mention my name, and I appreciate it. It’s cool to be recognized, but it’s not something that I was seeking or sought after. I never wanted to be famous.

Q: A lot of topline writers want to get in front of the mic in their own right. Is that something that you want to do?

A: No. I put out a couple songs when I was younger; a few years ago, I put out a mixtape, I put out a couple mixtapes. But I never did it to be famous. I was like, “Well, I could sing a little bit, let me see if I could generate some extra money, just to make a better life for everybody that I love.” It was like, if I could just get this song right here going on the radio, I could do some shows, and I could make a decent living, on the side of me writing songs, just to add more income. But other than that, I never had a desire. When I was younger, I wanted to be a singer, you know, with groups. But after a certain age I just realized that, really, I just wanted to be able to take care of my mom and my family, and if that was me writing songs, then that was cool.

Q: But a lot of topline writers do try, and some succeed, like Ne-Yo, or Sia, or John Legend. But a lot of them also fail; Ester Dean is an amazing topline writer but couldn’t cut it as a solo artist. Why do you think it’s hard for top-liners to make the leap?

A: Yeah, I think it’s just ordained, and I think that whatever’s meant to be in somebody’s life, will be. And I don’t think it’s something that anybody does right or wrong to get where they’re going. I just feel like maybe if it’s not your destiny, it’s just not your destiny, or it might not be your destiny at that time when you’re trying to make it your destiny. Maybe it’s just a timing thing.

I just feel like a lot of writers that wanna be artists, they do wanna be famous and they do wanna have that spotlight. And what I’ve noticed over the years is that most of these writers that have tried and have spent their own money investing in their own projects—they end up spending so much time focusing on themselves, that when that doesn’t work, and they go to try to come back in the writing for new artists, everybody’s onto the next writer. So I just notice a pattern of artists—writers getting so caught up on their own stuff, and investing time and money into their career—and then they look up and try to get back into writing and everybody’s like, on to the next person?

Just doing so, man, a lot of people shoot themselves in the foot ’cause they start focusing on their own stuff, but what’s really even got them to that point for them to be able to do that was writing for other people. So once you forget how you got to where you are, it’s tough to go into another field and do it when you got to where you were by writing for other people. So I always feel like if it’s something that happens organically, and naturally, without you actually trying and effortlessly, then I feel like it’s meant to be and it’s destiny. And that’s where I am with it.

Q: Record exec Clive Davis once said that pop singers need a “continuity of hits” to keep being relevant, and I imagine the stress is even more so for the people who are writing the songs.

A: One thousand per cent.

Q: And you talk about the cutthroat industry – do you have any stories of seeing how cutthroat that is up front, you know, in your own career?

A: For me, it was like, my first real experience with that, I was like younger than the average person. I was 12 years old, I was in the 7th grade, in middle school. I used to work with a group called Another Bad Creation. I wrote a rap and that rap was going out of a kids’ group called Kris Kross that were coming like, dissing ABC. And I wrote a rap dissing Kris Kross. And I wrote it for Red, for the lead singer, and I rapped it for him. And I wrote it down for him. And then I remember them disappearing for like, six months. And then I remember my friends coming in middle school, in class, in the morning, saying like, “Man, I heard that rap you did, on this album, on this Michael Bivins Biv 10 album,” and I was so excited, just cause I couldn’t believe it. And I heard it, and I started getting a little down because when I looked at the credits, the guy who stole it from me, he didn’t even get credit for it. His manager took the publishing. So that was like a very young age, me getting ripped off and just seeing how cutthroat, like just because you think somebody’s your friend, and you write something for somebody or you write something that’s for their project, it doesn’t mean they’re gonna give you credit. And cause I went through that at a young age, in a really cutthroat industry, and just getting ripped off from that, man, it was a learning experience. And it was cool for it to happen to me at such a young age, just so I could know, whoa—this is real and somebody just stole my song. And it came out and sold millions of records, so…

Q: What about experiences with the topline writer churn?

A: Oh yeah. That happened, definitely. The late 90s with my first success, with “Anywhere,” with “Peaches and Cream.” I thought it was a normality—you just write a song with an artist, and it comes out and goes on the radio, and it’s a hit, and you make money. And then you have a harsh reality of having a dry spell, where it’ll be two or three years where you won’t have anything on the radio. And you start questioning yourself like, “is this for me?”

And then you understand that those initial hits, they were accidents. I didn’t know what I was doing when I did it. It was just something that just happened. It wasn’t like I had a formula, or a style—it was something that I was just blessed to write with 112 and those records came out and they were hits. So doing it, separating from them and then not being part of machines like Bad Boy Music, it allows you to see that it takes a lot.

It’s like hitting the lottery to have a hit song. It’s not something that you just do. So that’s definitely discouraging and it comes a time where you wanna quit, you start thinking, “well, I need to do something else,” and then you just keep going and you just hope for the best, man. And definitely can be discouraging not having songs on the radio or on the charts in two or three years, but it just shows how persistent you are. If you really want it, if you’re really working hard, there’s a chance that you could do it again. It was accidental success, but it doesn’t mean that success can’t happen again if you surround yourself with the right people and you work hard and you’re honest with yourself.

Q: Something that struck me is this: In the National Football League, running backs’ careers are short, because of all the punishment they take and the athleticism they need to succeed. So even though they’re massive stars, they are seen as being past their prime by 30. People call the league “Not For Long” because of how disposable the NFL treats some of these players, who happen to be predominantly young Black men. And I wondered if there’s a similarity; the music industry has a lot of topline writers who are young people of colour. Is that something you’ve seen? Is there a relationship there?

A: I wouldn’t say that it’s just people of colour. There’s a lot of top-liners who are all races. I think that the music, the most current and relevant music that’s popular right now has been…yeah it’s definitely equal, it’s equal. With certain urban records, like the Drake records, and certain big urban records, it’s definitely more people of colour. But at the same time, you have a lot of hits of people that are not of colour. And I just feel like it’s a balance. I wouldn’t say that it’s more of a colour thing than it would be just a human being thing, honestly. Over the years, it’s like a healthy balance.

Q: It occurs to me also that it’s crazy that when you first hooked up with Justin Bieber, you had what, won four Grammys at that point?

A: Yeah.

Q: And yet many people felt it was a risk that he was taking, by jumping in with you and not, say, someone like legendary producer Max Martin.

A: Definitely, they did say that.

Q: What a weird thing, though. Because again—you won four Grammy awards! What were your thoughts on that at the time?

A: I was blessed to be part of those records that won those Grammys. And I just feel like people have their own perspective of what writers they want to be with what artists, and I feel like Max Martin is one of the greatest, man—22 number-ones, that’s amazing, it’s insane. I was extremely blown away by the fact that I was chosen, that I was blessed enough to write on that project. And even more, I don’t think it had anything to do with Grammys, more so than just Justin feeling like there was great music. And I think that outweighed everything else.

I don’t think people even looked at my success before. A lot of people didn’t even realize what I had done when I was working with Justin, nobody knew. Like I said, Justin was the first artist to mention my name. So I had done so much without anybody saying my name that people couldn’t even relate or say, “Oh wow, Poo Bear did this, he’s responsible for that.” So it wasn’t even an accolade thing, it was more like: nobody knew me. And I kind of liked it like that. I like being in the background. You can’t get tired of something that you don’t know.

Justin took a chance. He believed in his heart. He believed in what he loved and what we were creating, and I’m forever loyal to him for that.

Q: And there’s a flip side of people knowing about you: There was a lot of criticism of you in 2013, because at the time, Justin Bieber was involved in a series of controversies, and you were part of his entourage; at one point, you were even blamed for contributing to it. What were your thoughts on all of that, as it was happening?

A: For me, in life…everybody has to have their scapegoat. And everybody has to have somebody to blame. I just feel like everybody goes through things. Justin was very strong-minded and he was going through stuff on his own. And I happened to meet up with him at a place of his life where he was young, he was doing things that he wanted to do, and all I could do was just be there and support him. It was a lot of allegations and a lot of things that were said. But at the same time, you know, it’s just tough, man, on a teenager, and it’s tough on him being a superstar. And then for me, I’ve never worked with anybody on that level. So even for me coming in, for him—he was already doing what he was doing, and I just came in and all I was doing was just writing and being there with him.

And of course, everybody has to have somebody to blame. So of course, they choose the black guy to blame, and I was there to take that blame. And at the same time, you can’t control anybody, you can’t make somebody do anything or not do anything and all you can do is just be there and support. And I went through a lot of ridicule for that, and I’m just glad that the world saw that we came out of that ridicule. And even Justin being accused of so much…it was so false, it was so many lies that the media made up to sensationalize his story for ratings. I’m just glad that everybody’s seeing the more good side and the more positive side, and the media, finally—you know, everything turned around. And it was a really dark period but I’m just glad that we’re both out of that. And nobody’s blaming anybody anymore. They’re just buying his records and buying his tickets to see him perform.

Q: You’ve produced all kinds of music, from country and reggae to folk and comedy and, of course, pop.

A: Yeah, all that stuff is creating, man. I love making music. If I could make music to make people laugh, then that’s what I wanna do. If I could make music that can touch other peoples outside of English, then I wanna be a part of it. And reggae, Jamaican music—I just love music. So I feel like I can apply my formula that I use to write, and I can apply it to any genre, I can apply it to any language. And I feel like it’ll have the same outcome.

I haven’t met anybody else that has done as many different genres as I have done. I’ve seen a lot of writers, I’ve seen a lot of legends, but when I look at what they’ve done, it’s usually like one thing—like one specific, one particular sound that they stick to. For me, I moved to Jamaica, I lived in Kingston for six months. And I wrote a couple of albums on Jah Cure, like big reggae hits. And then I’ve done a couple of comedy albums that are coming out, they’re finished and just about to be released with a really cool platform. I just feel like I haven’t met any other writer that bounces around to different genres: they’re focused on making a hip-hop record hit, or they’re focused on making a pop hit, or they’re just focused on making a country hit. So for me, I always like challenging myself cause I just wanna know that I can do it. And for me, I just love pushing myself and seeing how many boundaries I can cross. And I can’t say that I’ve seen any other songwriter. Maybe there are other songwriters who can do different genres like that—I just haven’t met ‘em.

Q: So that’s your advice for young writers?

A: Focus on one thing until you get it really good, and then I would say yeah, go outside your comfort zone. See what else you can do because you never know what genre your next hit’s gonna come from. It allows you to plant more trees. It’s cool to be able to plant apple trees and get apples, but it’s cool to be able to plant a grapefruit tree or an orange tree as well. You never know. Your grapefruit tree, your orange tree, might produce just as much fruit as your apple tree. So it’s cool to get like, let me get the science of planting a really good apple tree and making sure it produces the best apples. But then, you know, once you do that, why not try other trees?

But I would say: become great at planting one type of tree before you just start spreading yourself thin. You wanna be able to have some success with one thing before—instead of trying to do it all at once. Because you’ll look up and everything will fail. But if you get one tree down pat, then you’ll be like, “wait a minute, I could use that same soil, that same water, that same sun to grow this different type of tree. And I’ll grow a different type of tree with different fruit.

So, I’ll definitely say to younger writers: get great at one thing, but then apply that one thing, apply that formula—how you did that one thing—to other things. You never know.

Q: “I’m The One” just debuted at number one on the Billboard charts. I don’t know if people know how hard it is get even one; Drake just got his first, with “One Dance.”

A: Yeah! After all the success he’s had. So that just lets you know how hard it is—you could be the biggest artist in the world and still not have a number one. So it’s a blessing, man – just to be able to do it more than once, more than twice is pretty cool. And hopefully we keep it going, man. My honest, my goal is just, hopefully, God willingly, I wanna put out five number ones this year. And we don’t have that much time, but John Lennon, Paul McCartney—these were writers that were able to, and they’re in the history books as being a part of five number one songs in one year. So that’s my goal, for this year—I’m gonna need five in order to tie with John Lennon and Paul McCartney. That’d be a great accomplishment for myself. That’d be really cool.