Paul Wells on Prince: A talent for genius

Virtuosic, inventive, and relentlessly prolific, Prince couldn’t help himself from creating music, and we’re all the better for it

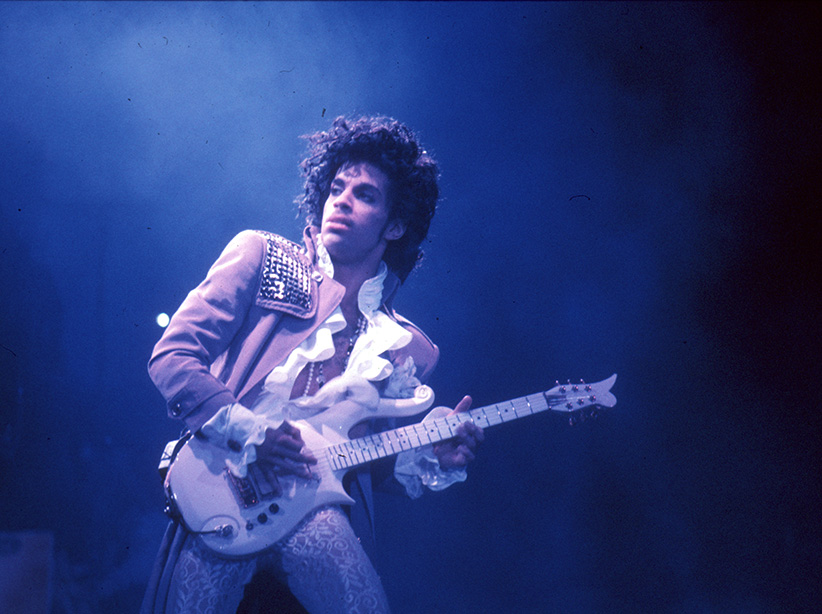

Prince performs live at the Fabulous Forum on February 19, 1985 in Inglewood, California. (Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

Share

It’s striking how often the lyrics in Prince tunes depart from their own storyline to comment on the construction of the song as it’s happening. “Horns, stand please,” he commands in “Sexy M.F.”, just before the horn line plays. Or in “Joy in Repetition”:

Up on the mic repeating two words, over and over again

Was this woman he had never noticed before he lost himself in the

Articulated manner in which she said them.

These two words, a little bit behind the beat.

I mean just enough to turn you on.

There have always been bandleaders with only a limited connection to the musicians backing them up, singers who didn’t know what key they were in, stars as comfortable with a recorded backup tape as with flesh-and-blood collaborators. Prince wasn’t one of those. His engagement with the structure and texture of the music around him was extraordinarily intense and sustained. On his first few albums—beginning with For You when he was 19 years old in 1978—he plays every instrument. On any of the astounding number of albums that followed, it was never entirely clear which bass, keyboard, drum or guitar parts were played by members of his various bands—the Revolution, the New Power Generation—and which by Prince.

It is difficult to attempt a definitive discography because it’s impossible to know where to stop counting: he so often turned up on colleagues’ albums without credit that the extent of his contribution to albums by, say, Morris Day and The Time, or by saxophonist Eric Leeds’ instrumental jazz/R&B band Madhouse, remains a matter of speculation among fans. Suffice it to say, he was astonishingly prolific.

Related: How Prince, rock’s effortlessly dangerous superstar, changed the game

The struggle over the copyright to all that good music led to him spending years peddling his recordings under the sign of an unpronounceable symbol—those were the “Artist Formerly Known as Prince” years. And to some extent it led him to exhaust and outrun most of his audience. After paying him little attention for years, I bought two of his last albums when he released them simultaneously in 2014: the self-conscious and unpersuasive Art Official Age and the loose, arena-rock-tinged Plectrumelectrum, the latter recorded with a new all-female backing band, 3rdEyeGirl. I was unsurprised to be reminded, just now, that he kept releasing new work even after that, including the tight, pop-bright HitnRun Phase One and Two last autumn. One of the tracks on those albums is called “Ain’t About 2 Stop”; it’s safe to assume that if he’d lived to be 80 he’d have kept releasing four or so albums’ worth of new material a year.

This level of output does have parallels in American popular music, but it far outstrips the leisurely productivity to which most other artists have accustomed their audiences. Surely a lot of Prince admirers—otherwise undeterred by his falsetto vocals, his unending psychedelia, his cartoonish sexuality and the way he used 2 many symbolz until U h8ed him 4 it—loved almost all the Prince they heard while simply wishing he would stop releasing so damned much. Most of the rest of the world simply stopped trying to keep up after a while.

I doubt Prince cared much. Even though he was jealous about copyright, much of his behaviour suggests that for him the main point of making music wasn’t to sell it, it was simply to keep recombining the fundamentals. “Joy in Repetition” was, like most of his other titles, largely autobiographical. I suspect he’d have kept making music if he’d been required to erase the files as he was going. He couldn’t help himself.

One hardly knows where to begin charting the breadth of his output. That he could make a hit out of a song as odd as “Kiss,” built from little more than bass drum, clavinet and blues falsetto, is amazing; that Tom Jones could cover the song and repeat the feat compounds the astonishment. The contrast with the lighter-waving ballad anthem “Purple Rain” is complete. For sheer density of invention and seriousness of purpose, perhaps nothing tops the 1987 double album Sign O’ The Times, from its searing title track (“In September, my cousin tried reefer for the very first time/ Now he’s doing horse; it’s June”) to the devotional anthem “The Cross,” I would put Sign O’ The Times right up next to the best albums from, say, The Beatles and David Bowie for sustained creativity. At just about every turn, Prince makes you laugh at his audacity. “I Could Never Take the Place of Your Man” is perhaps the only song in his discography that describes a young man turning down a sexual opportunity. His guitar solo on that track is a quarter-note rejection of the virtuosity in which he usually indulged. Here, as elsewhere, he tailored his work to the demands of the material at hand.

Beyond the particulars of this or that song, Prince’s music fits solidly into a tradition of R&B revues that made him the logical heir of Count Basie, Cab Calloway, James Brown and George Clinton. In fact Prince’s instrumental virtuosity makes him a bit of an odd fit with those men, who made their mark as contractors and instigators of outside talent. But like them—and especially like Clinton, who enjoyed a late-career revival when word spread that Prince’s sound came straight out of Clinton’s Parliament and Funkadelic collectives—Prince bet big on variety, an emotional range that stretched from silly to profound, and especially on rhythmic drive from the first note to the last. Miles Davis came out of the same tradition and took it to starkly different ends, but nobody should have been surprised that Miles and Prince saw each other as kindred spirits and recorded together, briefly and to limited effect, late in Davis’s life. It’s not entirely sure where that lineage goes after Prince. To Kendrick Lamar, I sometimes think.

Prince’s late concerts, usually played on short notice whenever the mood struck, were startling in their number, quality and in the large audiences that would drop everything to get to them. Like a fool, I missed a half-dozen chances in recent years to see him in Toronto or Montreal. He leaves so much compulsively produced music behind him that it’ll never really get old. Like the most prolific creators in any idiom—Mozart, Joni Mitchell, Christopher Hitchens—Prince’s legacy is an implicit rebuke to the rest of us: Knowing what they did, how can any of us be tired or weary or hesitant?