What Canadian pop moment?

Are Drake, Bieber and Co. on the Billboard charts a tipping point—or a warning?

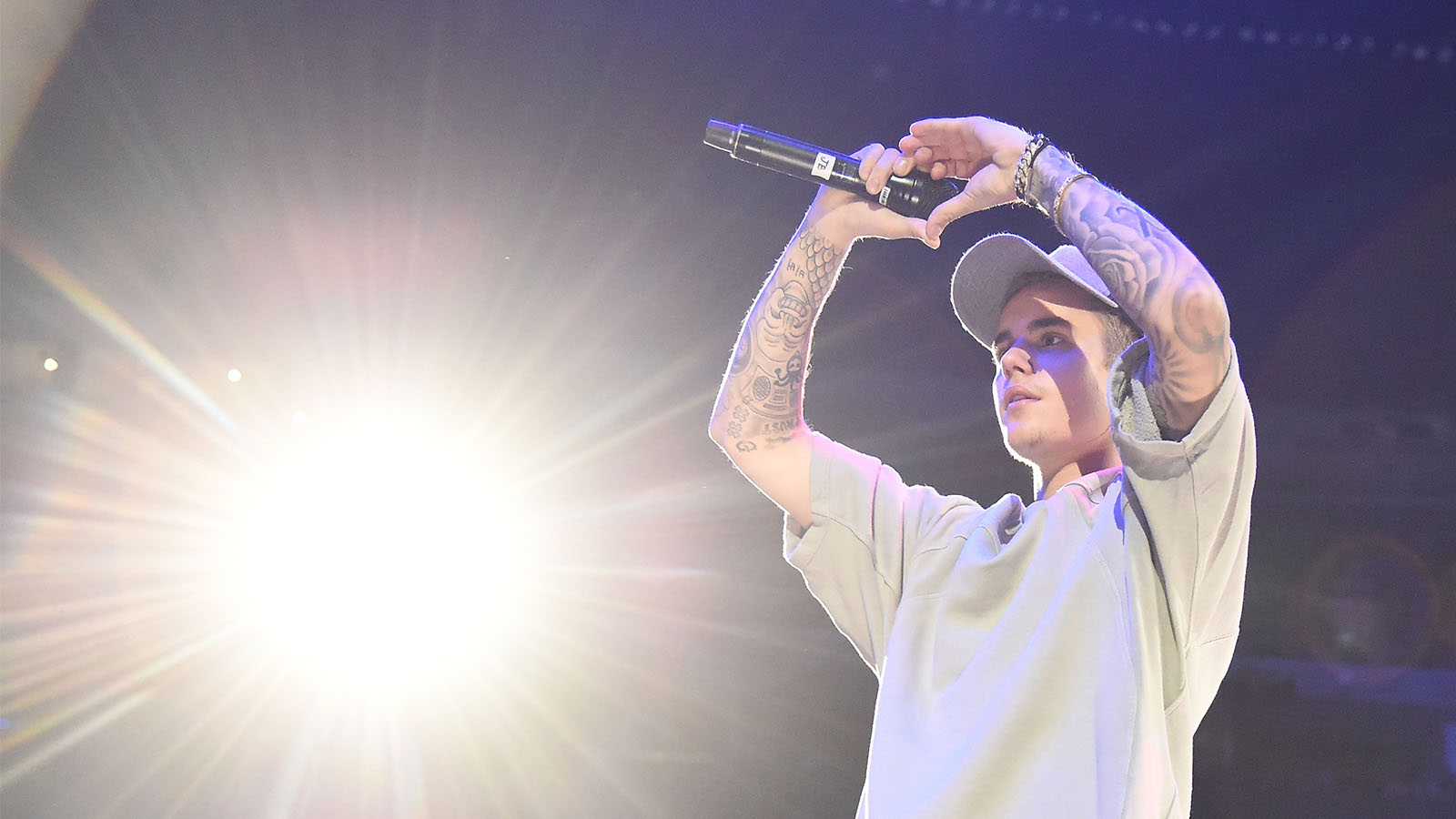

LOS ANGELES, CA – NOVEMBER 13: Singer/songwriter Justin Bieber performs onstage during An Evening With Justin Bieber at Staples Center on November 13, 2015 in Los Angeles, California. (Jason Merritt/Getty Images)

Share

The week of Dec. 5, 2015, is surely destined to be a Heritage Minute: Seven of the songs on the Billboard Top 10 were performed by Canadians. The triumphantly apologetic Justin Bieber sat at No. 2, No. 4, and No. 5 simultaneously; Drake’s ubiquitous Hotline Bling was at No. 3, The Weeknd’s The Hills at No. 6, Shawn Mendes’s clap-along Stitches at No. 7, and Alessia Cara’s disaffected teen anthem, Here, at No. 10 (it hit No. 8 the following week). All are from Ontario, and four out of five from the Greater Toronto Area—with Justin Bieber, from Stratford, close enough to have a Toronto concert considered a “hometown” gig.

This takeover has been heralded as a triumph for Canadian pop. But just how Canadian are its roots? All five artists are signed directly to various of Universal Music’s U.S. divisions, and only distributed via Universal Canada (The Weeknd is signed to both.) Where The Weeknd and Drake developed their early mixtapes in Toronto (even then, dual citizen Drake was working back and forth across the border), Bieber was discovered on YouTube by Atlanta manager Scooter Braun, who moved him to the States. Similarly, Cara and Mendes were discovered singing covers on YouTube and Vine, respectively—Cara by a New York manager and Mendes by an L.A. production company—and both were matched up with U.S. co-writers. Although Drake now signs local artists to his label, OVO Sound, the label is described as a “partnership” with Warner U.S.

Not since the likes of Céline Dion and Bryan Adams have globally popular Canadian artists signed directly in Canada to launch their careers. It’s difficult to use a Canadian label to export pop music across the border, says Drake’s entertainment lawyer, Chris Taylor, as “the gatekeepers in the U.S. determine where budgets are expended—and they’re expended on artists they sign.” Homegrown icons such as Blue Rodeo and The Tea Party, who signed domestically here, were never given the time of day in the U.S.

What’s more, signing to a U.S. label offers an insurance policy. In 2013, The Weeknd’s first album recorded after his signing, Kiss Land, failed to yield a hit. Says Taylor, “You don’t get another shot the way he has unless you’re signed down there and somebody’s ass is on the line.” Even for artists who sign in the U.S., says Ron Lopata, VP of A&R for Warner Music Canada, “maybe 10 per cent” of such deals succeed.

Independent labels can push hard for their artists—as Taylor’s Toronto-based Last Gang has done with the likes of Metric—but they face an uphill battle. “They’re being squeezed by the majors on one side and by costs on the other,” says Larry LeBlanc, senior correspondent for CelebrityAccess, who has written reports for Heritage Canada on exporting Canadian music. In the mid-1980s, funding group FACTOR was set up to help independent labels and artists; thanks to the shrinking record industry, it now effectively supports the majors too.

Certainly the image of Mendes, Cara and Bieber singing alone into their webcams in Pickering, Brampton, and Stratford doesn’t suggest much of an actual scene. On the other hand, the GTA’s immigrant culture, which isn’t fixated on rock as Canada once was, is poised to take advantage of the global popularity of pop and urban music. With Drake and The Weeknd employing kids from the suburbs to make beats, an ecosystem of writers, producers, and performing artists can grow around them.

Michael McCarty, an executive at performing rights group SOCAN, notes a growing investment in the GTA by U.S. production companies that see the city as a hotbed of pop: “We’re the new Sweden!” And as Toronto’s own pop stars maintain home bases in the city, they’re more likely to attract international talent around them. Globalization can help a local scene flourish, and it’s no longer necessary to leave for the U.S. to be noticed there—or to leave other parts of Canada for the GTA. Edmonton singer Ruth B, for instance, was snapped up by Columbia in July after one of her songs went viral. As music industry barriers come down everywhere, says LeBlanc, “this is the Wild West, and Canadians are taking advantage of it.”